The River Torrens (Karrawirraparri) was not only crucial to the siting of Adelaide as South Australia’s capital city, but it also has in several ways continued significantly to influence the life of the city and adjacent regions.

Course of the river

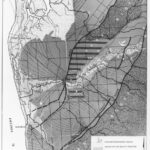

The River Torrens was named by Colonel William Light in 1836 in honour of Sir Robert Torrens, the chairman of the South Australian Colonisation Commission. It rises some 55km east-northeast of Adelaide in the Mount Pleasant district of the eastern Mt Lofty Ranges and only 20km from the eastern scarp of the upland. Draining an area of about 500km2 the Torrens flows westwards across the ranges, cutting a deep gorge before emerging on to the Adelaide Plains at Athelstone. For the next 7–8km the river runs through a series of basins and shallow defiles, with steep south-facing bluffs. Then, from Hillcrest to Adelaide, the river runs in a deep channel cut into old valley floors or terraces, so that Walkerville Terrace, for example, runs along a physical feature of the same name, while Mann Terrace is located on the slope linking two such old valley floors.

Though it has since incised its bed, the character of the valley changes abruptly to the west of Adelaide, for the river leaves its confined valley and spreads out on to the plain. Formerly the river flowed northwest toward the Port River, but the sediment picked up in the uplands choked the channels and the Torrens was diverted to the west migrating laterally before eroding its present channel, creating swamps, marshes and, notably, the ‘Reedbeds’ behind the sand dunes which front the coast, before draining north to the Port River or south to the Patawalonga.

Importance to Adelaide

When Light sought a site for his capital city he had in mind specific requirements. The plains were wooded and fertile, and the site was to be within easy reach of the Port River harbour. Building stone was available locally and in the nearby Adelaide Hills. Routes through the ranges were accessed first via Anstey Hill and later via the Torrens Gorge. The flow of the river is seasonal, but it was thought that even in summer the waterholes of the Torrens would furnish an abundant supply of potable water; though whether it was reasonable to describe it – as it was at the time – as ‘delicious’ and ‘fresh’ – is questionable. Notwithstanding, the river still supplies water for local irrigation and domestic use, and on a larger scale for several water conservation schemes serving the Adelaide metropolitan area, both in the past and at present. They include the weirs at the mouth of the Gorge (1857) and near Gumeracha (1918), and the reservoirs at Thorndon Park (1860; decommissioned in 1986 and converted to a recreation area), Hope Valley (1872), Millbrook (1918) and Kangaroo Creek (1969).

Changes to the Torrens

The river was, however, a mixed blessing, and it is no exaggeration to state that during the first century of settlement much time and money were expended on attempts to control the river and the problems it posed, especially for the areas west of the city. A direct outlet to the sea was excavated through the coastal sandhills at West Beach, channels were straightened and cleared, and the flood danger mitigated with the construction of dams, and especially the Torrens Dam (or weir) west King William Road in the city in 1881, behind which was formed the Torrens Lake.

Siltation built up the beds of the channels (it is recorded that about 1.5m of sediment were deposited in the river channel east of Henley Beach between 1909 and 1925) and the likelihood of flooding was increased as the capacity of the channels was reduced. This was, to put it mildly, inconvenient. In September 1863, for instance, the river came down in flood and some members of the congregation at the Fulham Wesleyan Church were cut off from their houses on the opposite bank. To reach their homes they had to travel via Hindmarsh, a trek of almost 18km to attain a distance of some 800m.

Yet the river waters and contained sediment were a valuable resource in these same flood-prone areas. In 1886, when the supply diminished as a result of flood control and particularly the completion of the Torrens Dam, a Mr White of Fulham Reedbeds, claimed damages against the Corporation of Adelaide, contending that he was disadvantaged by his not receiving the river’s ‘natural flow’.

Challenges

The Torrens was everywhere a physical barrier between north and south. The channel was negotiated at first by fords and footbridges and, between Adelaide and North Adelaide, also by a punt pulled by a rope. Road bridges were constructed, but all sustained flood damage so that for many decades their repair and reconstruction were a considerable burden on the public purse. Also, several people were drowned trying to cross the river. In September 1841, for example, the nurse and daughter of Mr and Mrs Charles Mann were drowned attempting a crossing at Klemzig. The river in flood brought with it a welcome supply of firewood, and cartloads were obtained from the flooded waters, but rescuing it from the torrent was not without its hazards: in June 1855 10-year-old Thomas McCann drowned when attempting to collect wood from the Torrens at Bowden. The river and the associated Torrens Lake continue to trap and claim the careless, unwary or just unlucky.

Floods also wrought severe damage on the many market gardens and orchards located on land near the river to take advantage of water and good soil, both in the metropolitan area and upstream in the Adelaide Hills. Soil, produce and buildings were frequently lost or damaged. Other riverside properties were not immune. In September 1844 the river ran high and destroyed a starch factory at Walkerville and a brewery in Adelaide. Club boat houses have been damaged or washed away from time to time.

Recreation

By 1862, however, there were those who perceived the recreational possibilities of the river and its valley in the vicinity of Adelaide. In 1862 ‘Cataractus’, writing to the Register, proposed that two footbridges ought to be built across the Torrens, and that the river be dammed near the gaol. This would convert the river and its valley into a lake, which would beautify the area and make it into one where Adelaideans could take their leisure. That dream became a reality in 188l; though what is regarded as ‘leisure’, and ‘entertainment’ varies both individually and in time. A footbridge opened in 2014 was constructed across the Torrens Lake connecting the refurbished Adelaide Oval and the Convention Centre–Casino complex to the south. Linear parks have been constructed along the river both to the west and upstream from the city, where the O-Bahn busway also utilises the valley corridor.

As a result of damming the river, sediment and other debris which was formerly carried and deposited to the west, in the Reedbeds, was trapped behind the dam, necessitating the periodic draining of the lake and clearing of the accumulated debris. Algal blooms can also be a nuisance in summer. But the Torrens Lake, with its birds and boats, and its adjacent lawns and gardens, popular for picnics and for quiet contemplation, its restaurants with alfresco dining, and its associated sports venues, undoubtedly enhances the city centre and is a welcome and popular development. For thousands, the Torrens Lake is synonymous with the ‘Popeye’ boat and paddleboats.

Though the river and its environs have always had their darker side, they are, by and large, a picturesque amenity located in the very special parklands. They are greatly appreciated by residents and visitors of all ages.

Comments

2 responses to “River Torrens”

adilaide is so small but we hate it when other people say that

Adelaide*