King William Street, the north–south thoroughfare bisecting the City of Adelaide, is named after King William IV. The name was chosen on 23 May 1837 by a Street Naming Committee made up of the governor and eleven prominent colonists.

During the short reign of William IV (1830–37) political reforms were enacted, including changes to the electoral system. Following the reforms, previously stalled proposals to establish the Province of South Australia were accepted by the British Parliament which passed the South Australia Act 1834. The Act was brought into effect by the Letters Patent signed by William IV on 19 February 1836.

Of the eleven east–west streets planned, nine bear names separated by King William Street. Popular belief holds that this reflects the convention that no subject was permitted to cross the path of the monarch. Given that both North Terrace and South Terrace are named geographically, this may appear to be true. But this naming pattern enabled more names to be assigned to the few streets laid out by Light. Besides, both the north–south Pulteney Street and Morphett Street had separately named sections as do some streets in North Adelaide.

Prominent public buildings

Colonel William Light, Adelaide’s surveyor and planner, settled on a grid layout for the City of Adelaide in 1837 after the site was selected. Within this grid, land was divided into single-acre allotments. Some of these ‘town acres’ were sold in Britain before European settlement began. Others were sold by auction after the city was laid out.

Light’s Plan of 1837 suggests that he intended the city centre to be Victoria Square and for King William Street to be the main street. He provided for a cathedral within the square and set aside four acres bordering the square on King William Street for government offices and an acre on the southeast corner of Pirie Street and King William Street for a town hall.

A government construction on the corner of King William Street and Flinders Street, on the northern side of Victoria Square, in late 1839 housed the offices of the colonial secretary, treasurer, accountant, and the Lands and Survey Department. Treasury vaults were added in November 1850. The vaults contained furnaces to smelt gold from the Victorian gold rushes of the early 1850s. Most of the building was demolished in stages between 1858 and 1907. It was replaced by two and three-storey additions in the same style. The central courtyard and garden of the original building and the vaults were retained. The complex of offices became known as the Treasury Building.

In 1881 new government offices were built to meet the needs of the growing colony. The imposing Torrens Building on the eastern side of Victoria Square was a very short distance from the Treasury Building.

The Adelaide Town Hall, built north of the Treasury Building in 1863–66, was then the tallest, grandest and most expensive structure on King William Street (Marsden, Stark & Sumerling, p163). It became the prime venue for balls, concerts, civic receptions and public meetings. The faces of the Albert Tower (named after Queen Victoria’s consort) remained empty for seven decades until Councillor Sir John Lavington Bonython, a former mayor, donated an electric clock.

The General Post Office, incorporating the Telegraph Station, was constructed opposite the Adelaide Town Hall between 1867 and 1872. This grand two-storey building incorporated a large public hall with a decorative cast iron balustrade around a gallery. The sides of its half-dome ceiling were made of glass. Centre panels were richly decorated. The foundation stone for Victoria Tower (named after the queen) was laid on the King William Street frontage in 1867 but the clock, bells and dial facings were not installed until 1875.

The Victoria and Albert Towers continue to frame the vista along King William Street.

The Law Courts

The southern stretch of King William Street from Victoria Square is dominated by law courts. Like other public buildings, the early law courts were grouped around the street’s junction with the square.

The first court built was the Supreme Court (now the Magistrates Court) on the corner of King William Street and Angas Street. One of the oldest public buildings in Adelaide, it features a distinctive façade of golden sandstone. Completed in 1851, in that August the ceremonial opening of the first session of South Australia’s Legislative Council was held there. The Supreme Court judges were soon dissatisfied with its lack of space and facilities, and so this court was transferred to the larger local court building in 1873, which then became, and remains, the Supreme Court.

The original Supreme Court was followed in 1867 by the Police Court, built on the opposite side of King William Street on acre 408. Offices for the Commissioner of Police were added in 1868.

The Local and Insolvency Court (now the Supreme Court) adjoins the Police Court on the southwest corner of Victoria Square. Although begun before the Police Court, this more substantial building was not completed until 1869.

North of Victoria Square: Banking and insurance

Contrary to Light’s intentions, European settlement of the City of Adelaide did not focus on Victoria Square or King William Street. It centred on the northwest corner close to the River Torrens water supply and the track to Port Adelaide. Cost of land and preferences of landholders also forced residents and small businesses away from the planned main street. Colonist EW Andrews noted in 1838 that ‘The centre of the city is Victoria Square and the principal street is King William Street, but in the first instance land in this neighbourhood was so very high, and the proprietors so little disposed to suffer common buildings to be erected there, that the shops became chiefly collected in Hindley Street’ (in Marsden, Stark & Sumerling, p18).

Increased economic activity following the development of copper mines from the mid 1840s and the expansion of pastoralism and agriculture generated demand for financial services together with the capacity to supply such services. Profitable financiers, banks and insurance companies were able to afford the cost of land and rents along King William Street. North of Victoria Square the street progressively became an avenue of grand and ornamental financial premises.

One of the first to erect substantial offices on the desirable corner of King William Street and Rundle Street was Thomas Greaves Waterhouse, financier and a director of the South Australian Mining Association which owned the huge Burra Burra mine. Waterhouse Chambers, largely funded from the profits of that copper mine, was completed in 1848 and is still standing.

A large number of banks were constructed along the street during the following decades. The Bank of Australasia, the Bank of New South Wales, the Savings Bank of South Australia, the English, Scottish and Australian (ES&A) Bank and the National Bank of Australasia were all built between 1851 and 1867. The Imperial Fire Assurance and Insurance Chambers buildings also added to the congregation of solid stone edifices. None of these buildings remain: many were demolished in the 1960s and early 1970s.

A further wave of even grander construction came with some of the prosperous years in the late 1870s and 1880s. Perhaps the most impressive of these new buildings was designed in 1878 for the Bank of South Australia by architects Lloyd Taylor of Melbourne and Edmund Wright of Adelaide. This ornate building was renamed Edmund Wright House in 1971 when it was saved from demolition. Another building of merit surviving from this time is the former Bank of Adelaide on the southern corner of Currie Street, although the effect of its particular contrasting use of light and dark coloured stone was lost when the building was extended in 1939. The Commercial Bank of 1889, designed by architect Edward Davis, also featured a decorative façade and roof domes.

Several banks were rebuilt during this period. In 1882 the new ES&A Bank challenged the dominant style of weighty stone, with a much simpler, smooth and elegant gothic exterior. It was in stark contrast to the substantial Bank of New South Wales rebuilt in 1888 on the corner of King William Street and North Terrace. The Bank of Australasia was rebuilt and expanded in 1887 with a new building that curved around the corner of King William Street and Currie Street. The original Australian Mutual Provident Society’s building of 1886 replicated the solid structure common amongst the banks.

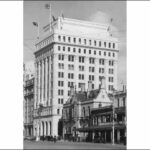

Apart from some additions to the number of insurance premises, there was little expansion of financial institutions along King William Street from the depression of the 1890s until the end of the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s. An important exception was the Temperance and General Mutual Life Assurance Society’s building on the corner of King William Street and Grenfell Street. The T&G building, one of the first high-rise buildings in Adelaide, reached 11 storeys and 40.2m (132ft). This was the maximum height then allowed for city buildings. For many years it was the most prominent landmark on King William Street.

In the mid 1930s financial institutions along King William Street north reasserted their wealth and power with the construction of high-rise establishments, with some replacing previous premises. The modest Commonwealth Bank building between Grenfell Street and Pirie Street was replaced by a much larger modernist structure with an imposing pillar-framed entrance. The new Bank of New South Wales building on the southeastern corner of King William Street and North Terrace adopted a similarly simple but substantial, modernist design. The Australian Mutual Provident Society’s premises on the corner of King William Street and Gresham Place rose to 12 storeys. Its understated, adapted Renaissance style exterior of granite and sandstone belied the grand interior. Coloured marble lined the walls and counters, and walnut, jarrah and blackwood timbers enriched fittings and furniture.

But the most prestigious financial premises built during this period were those of the Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Co. Completed in 1935, the building featured neo-Romanesque details, including stone lions and vultures arching over the street below. A tower and mansard roof extended the building’s height. In 2013 work began to convert this building to a hotel.

The ultimate statement of banking confidence was made in 1986–87 with the erection of the thirty-one-storey State Bank building, the tallest building in Adelaide. In replacing the Savings Bank (later State Bank) premises of 1939–43, the brown skyscraper dwarfed surrounding buildings and truncated neighbouring structures. The bank was proud of the major works of art housed within its walls. Following the collapse of the State Bank in 1991, the building was taken over by the South Australian energy company Santos in 1997, but reverted to its banking origins in 2007 when the Westpac Bank secured naming rights.

Few major financial premises were constructed along King William Street after the Second World War.

South of Victoria Square

The character of King William Street changes noticeably south of Victoria Square. It continues to reflect the slow and small-scale development of the city away from the early settlement of the northwest corner and later bustling streets closer to North Terrace.

Kingston’s Map of 1842 shows only a handful of structures of any kind along King William Street south, in contrast to the concentrations of buildings to the north.

However, by 1875, a range of premises provided services for the nearby courts, other larger city businesses and the many residents of the city. Solicitors, butchers, bootmakers, blacksmiths, and wood and chaff dealers lined the eastern side. The Crown and Sceptre Hotel near Victoria Square served local residents, lawyers and workers, and prisoners appearing in court were sent meals from there. The station for trains to and from Glenelg was located immediately south of Victoria Square. The western side of King William Street south also housed various building trades, stores and personal services, including a tailor. Closer to South Terrace residences and boarding houses were more common. The Kings Head Tavern and the Brecknock Hotel provided a relaxing venue for workers and residents.

Not much had changed by 1900. Small shops and trades premises still dominated the street. The nature of these businesses was a little broader than previously. The appearance of booksellers, chemists, a veterinarian and a signwriter indicate some diversification of services.

Half a century later, while small business predominated, a few larger manufacturing and related premises were present, including Jacobs Dairy Produce and Bacon Manufacturing, British Engineering Appliance Ltd and a Myer Emporium bulk store. Services connected with motor vehicles had arrived with a garage and Central Service Cabs. Community associations such as the Theosophical Society, Caledonian Society and Nationalist Association were no doubt attracted by the cheaper rents in this part of the city.

By the end of the twentieth century, businesses had changed, but the essential small-scale character of King William Street south remained. Rare exceptions to this were the multi-storey building constructed in 1990 at 431–39 King William Street, which still stands alone on the corner of South Terrace, and some large residential accommodation near the corner of Gilles Street which was constructed in the twenty-first century on the site where Holdens motor body building premises had been from 1919.

An avenue for transport

As the main north–south corridor through the city and the route connecting government offices on Victoria Square and Parliament House on North Terrace, King William Street became a focus for both transport and public events.

By the 1870s groups of horse carriages and Hansom cabs were available for hire along King William Street from North Terrace to Victoria Square. Horse-drawn trams, pulled along metal tracks laid down the middle of the street, were added in 1878. The trams connected travellers with the Adelaide–Glenelg railway, which ended at Victoria Square. The railway ran from 2 August 1873 until replaced by new electric trams in 1929: electric trams had taken over from horse drawn trams in the metropolitan area in 1909.

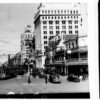

Images of King William Street north between the 1870s and late 1920s show a bustling street full of pedestrians and various means of transport. For much of this period there is little evidence of traffic control. People alight from vehicles and weave in all directions amongst the traffic. Traffic lines and lights begin to appear from the 1930s.

Electric trams were removed from King William Street in 1958 to allow for the unimpeded flow of motor buses and cars. A renewed emphasis on public transport at the beginning of the twenty-first century saw trams reintroduced on King William Street north of Victoria Square to North Terrace west and Port Road.

Parades and events

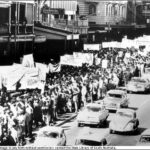

Traffic on King William Street north is periodically stopped by marches and parades. Since the Boer War (1899–1901), contingents of soldiers have marked their leaving and return in a march along King William Street. Peace has been celebrated with parades and mass gatherings outside Adelaide Town Hall. Commemorative Anzac Day parades have filed along the length of the street.

Anti-war demonstrations have also focused on King William Street since the 1960s in particular. Meanwhile, protest rallies shifted their location from Speakers Corner in Botanic Park to Victoria Square. Rallies have generally been followed by a march to Parliament House. Issues of concern to Aboriginal people, women, gays and lesbians, labour unions and crusades by the general population are highlighted by marches along King William Street. The marchers’ chants echo between the walls of buildings along the thoroughfare.

The Christmas Pageant that now begins at South Terrace and ends at North Terrace east is the only parade that travels the length of King William Street. Presented for children since 1933, when it began at Angas Street, the parade’s colourful floats, bands and costumed characters lead Father Christmas and a queen and king in a long procession. The huge crowds enjoying the event adhere to the blue line painted on the road.

Since 1973 the annual City-Bay fun run and walk has used King William Street, at first from the Town Hall, then North Terrace west and from outside the Festival Theatre since 1997.

Other parades have celebrated the state’s history, particular events (such as Australia Day parades which end at Elder Park), the Festival of Arts and, in recent years, the Fringe Festival.

The protests and celebrations may stop the vehicle traffic, but they are a vital part of Adelaide and reinforce King William Street as an important aspect of the city’s economic, political and social life.