From the beginning of European settlement, East Terrace has been a street of contrasts. Mansions occupied by Adelaide’s wealthy lined the road to the south while the northern end housed the poor in crowded tenements among industry. Nearby a fruit and vegetable market operated from the early hours of the morning.

East Terrace is the only street in Colonel William Light’s Plan of the City of Adelaide that is not straight. The terrain did not permit it to be so. It forms the angular eastern boundary of the city where it extends out across the plain towards the Adelaide Hills. East Terrace connects the busy cultural hub of North Terrace to the secluded east end of South Terrace.

Streets terminating at East Terrace from north to south are: Rundle Street, Grenfell Street, Pirie Street, Flinders Street, Wakefield Street, Angas Street, Carrington Street, Halifax Street and Gilles Street. The terrace is bordered from north to south by: Kadlitpina/Rundle Park/Park 13, Murlawirrapurka/Rymill Park/Park 14, Ityamai-itpina/Park 15 and Pakapakanthi/Victoria Park/Park 16.

Aboriginal associations

The Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains used Kadlitpina/Rundle Park/Park 13, Murlawirrapurka/Rymill Park/Park 14 and Ityamai-itpina/Park 15 before and after European settlement for particular activities. The Botanic Creek through Kadlitpina/Rundle Park was directly associated with Kaurna use.

From the 1880s Ngarrindjeri man Poltpalingada Booboorowie (also known as Tommy Walker) camped in these three parks. He became a leading man in the Aboriginal community that lived on the ‘fringes’ of Adelaide and a well-known identity in colonial society. On his death in 1901 members of the Stock Exchange of Adelaide paid for a headstone in the West Terrace Cemetery. It was later revealed that the state coroner, William Ramsay Smith, had removed Tommy Walker’s skeleton before burial and sent it to the University of Edinburgh, making up the weight in the coffin with sand. In the early 1990s the university repatriated his remains and he was buried with ceremony at Raukkan Aboriginal Community.

Early settlement on East Terrace

Light’s plan of Adelaide as printed in 1840 shows 20 ‘town acres’ set out along East Terrace. Eighteen of these acres were preliminary purchases made in England prior to European occupation. Three were bought by the South Australian Co. and four by John Wright, a London banker. Osmond Gilles, the first colonial treasurer, and Nathanial Alexander Knox, an officer of the East India Co. and a founder of the Adelaide Club, bought an acre each. By August 1839 Emigration Agent John Brown had occupied a dwelling on acre 357, one of Wright’s purchases, on the northeast corner with Angas Street: his residence and most of the contents were destroyed by a fire on 30 November that year.

Two years later, George Strickland Kingston’s map reveals little construction on East Terrace, except between North Terrace and Pirie Street. Dwellings and other buildings were scattered and few. Two substantial wooden homes with verandas had been constructed on acre 31 on the corner with North Terrace. They were occupied by Captain Butler of the 96th Regiment and John Morphett, investor in the South Australian Co. and later the first speaker of South Australia’s Legislative Council (1851–55). Between Halifax Street and Gilles Street the Rev. James Farrell, first Anglican Dean of Adelaide and second incumbent of Holy Trinity Church (1843–68), lived in a large wooden residence.

Peacock’s tannery and the Rookery

In about 1842 William Peacock constructed a tannery on a twin acre site between Rundle Street and Grenfell Street. Peacock was a businessman, a director of the South Australian Mining Association and an Adelaide City councillor and alderman. In 1851 he was elected to the Legislative Council. The area around his tannery became infamous as the ‘Rookery’ due to the overcrowded and sub-standard housing it provided for poor working class residents of Adelaide.

A two-storey building divided into 18 individual tenements occupied the northern side of the tannery yard. The upper tenements were accessible only by stepladders. In 1849 the building housed approximately 100 people. Peacock also built two sets of workers’ cottages on the site in the 1850s. One row of 12 cottages sat opposite the tenements. They were reported as ‘all thickly inhabited and having but one privy among them’ (Leevers, p6). Another row of nine cottages had one room each measuring 3m by 6m with a hearth and shingle roof. They had an entrance on both their southern and northern sides and were served by just three cesspits and one water tank. Women made up most of the listed tenants.

The unhealthy nature of the Rookery was made worse by its proximity to not only the tannery, but also to the rubbish dump in Park 13. Refuse of all descriptions was deposited in the area up to Botanic Creek through the 1850s and possibly longer. Not surprisingly occupation was generally short-lived. In 1899 the Rookery was finally condemned by the Adelaide Council’s health inspector as ‘unfit for human habitation’.

The Stag Inn

Also located between Rundle Street and Grenfell Street was the Stag Inn, constructed in 1849 by its first licensee George Taylor. The hotel had attached stockyards, stables and a weighbridge for the buyers and sellers of produce who used its yards as a market area. After the East End Market was established in the 1860s the produce trade ceased, but the Inn continued to provide refreshments for early morning traders. Until 1884 the Stag Hotel also had a dance and concert hall at the rear.

The Stag Inn was owned by George Taylor and his executors until it was sold to Thomas Richardson in 1902. Richardson demolished the original building but retained a double-fronted western section that had been added in the 1870s. He commissioned Adelaide architects Garlick & Jackman to design a new hotel around this section. The Stag Hotel featured a distinctive attic storey, turret, return veranda and balcony. The tiled roof and cast-iron balustrading were typical of the period. There was more accommodation for market patrons in the enlarged hotel.

The Stag Hotel has had an unbroken existence from 1849. However, a stone shed behind the hotel is all that remains of the extensive sheds and stables that once surrounded it.

The 1860s: the East End Market and Hotel

In his plan of Adelaide, Colonel Light set aside an area in the west parklands for a fresh produce market, but this aspect of his plan was never implemented. Several markets operated elsewhere in the early life of the city. A cattle market was situated opposite the Newmarket Hotel on North Terrace west. In 1840 George Strickland Kingston designed a market for the South Australian Co. at the corner of Rundle Street and Gawler Place. From 1841 until the 1850s the area now occupied by the Adelaide Town Hall was also used for a market.

These sites gradually became unavailable or inadequate as Adelaide’s population grew and building density increased. Businessman Richard Vaughan responded to demand by constructing the East End Market on East Terrace between North Terrace and Rundle Street in 1866. He roofed his wholesale and retail market in that year and enlarged the facility in 1869. The East End Market was followed by the Central Market, established by the Corporation of the City of Adelaide near Victoria Square in 1869.

GE Holtermann constructed a hotel next door to the East End Market to cater for patrons, especially growers. The one-storey East End Market Hotel was completed in 1868. A second storey was added in 1875. The hotel survived a fire in the locality in 1926 and continues to operate in the twenty-first century.

A split personality: East Terrace in the late nineteenth century

North Terrace to Pirie Street: workers and industry

The mixed-use northern end of East Terrace in the 1870s and 1880s was very different from the residential southern end. People lived amongst industry in a row of two-storey terraces, small cottages and the Rookery. Boarding houses also offered accommodation. The occupations of residents were overwhelmingly working class and included labourers, boot makers, caretaker, laundress, gardener and blacksmith. The occupations of women were generally not given, although directories record Mrs Kidd’s School and Miss Caroline Lindstrom, music teacher.

Fumes and noise emanated from the industry around workers’ homes. The SA Jam Co. works, the tannery with its tall chimney, a soap factory, a shoeing forge, timber merchants and a saw mill operated between North Terrace and Pirie Street. The area was also a hive of commerce. The busy East End Market hosted wholesale and retail traders from the early morning and was in turn served by stables, the Stag Inn and East End Market Hotel. Coffee rooms and fruiterers’ shops were located nearby.

The big end of town: East Terrace mansions

South of Pirie Street, the character of East Terrace changed to residential. Prominent, wealthy Adelaide identities built mansions in this quiet area overlooking pleasant parklands. Unlike Parks 13 and 14, Ityamai-itpina/Park 15 and Pakapakanthi/Victoria Park/Park 16 had no rubbish dumps. From the 1850s the principal use of Victoria Park was as a racecourse. Racing was popular with Adelaide’s elite who provided the membership of the Adelaide Racing Club, formed in 1871 to run the racecourse and park. A tree-lined carriageway constructed in the 1880s gave access to the racecourse from East Terrace.

The large wooden homes built on East Terrace in the early years of settlement were gradually replaced by substantial stone and brick residences. The boom period of the 1880s in particular saw the construction of several mansions, some of which have survived into the twenty-first century.

Rymill House, built in 1881 on acre 220, was owned by land and estate agent Henry Rymill. An extant coach house facing 22 Hutt Street was part of the original establishment. ‘The Firs’ as it was then named, was designed by architect John Haslam and built by William Rogers. The two-storey Queen Anne style building was constructed of Sydney stone. It featured the latest ventilation, sanitary and plumbing arrangements. The Rymill family occupied the house until 1950 when it was purchased by Australia Post and used as a training facility until 1982. The building then reverted to a private residence.

‘Dimora’, at 120–24 East Terrace, was built in 1882 for Harry Lockett Ayers. Besides being a son of Sir Henry Ayers, his occupation in a trustee and financial agency placed him in Adelaide’s financial and social elite. Ayers was a foundation member of the Adelaide Club and a member of the Adelaide Hunt Club. The house, with 20 main rooms, including ballroom, is thought to have been designed by William McMinn. It remained in the Ayers family until 1940.

‘Ochiltree House’, on a South Terrace corner, was constructed in 1882 for businessman and pastoralist John Rounsevell. The striking design is thought to be by architect be G Jaochimi. It includes a combination balcony and projecting veranda with elaborate iron lacework; replicated on the front fence. The patterned slate mansard roof highlights the main entrance, which is set between two large bay windows. A preservation campaign in the 1970s saved this heritage listed building from demolition.

The former Wesleyan manse at 156–58 East Terrace was built in 1885 by architect John Haslam. It was used as extra accommodation for Wesleyan clergy of Pirie Street Methodist Church for only 12 years before being sold to James Henderson. He named the residence ‘Duntocher’. This two-storeyed residence has a veranda and balcony on both the front and side faces. It is constructed of sandstone with stuccoed and brick dressings.

The largest surviving mansion on East Terrace is ‘Eothen’ (later ‘St Corantyn’), constructed at the beginning of the 1890s to the design of architect George Klewitz Soward. It was built for Soward’s sister and her husband Charles Atkins Hornabrook. The interior decoration features elaborate carved timberwork and stained glass. St Corantyn also has an association with other prominent Adelaide citizens, including furniture emporium proprietor Malcolm Reid (1912–28) and Lord Mayor Sir John Lavington Bonython (1928–62). In 1962 it was sold to the South Australian Health Commission and became a mental health services day hospital, before reverting to a private residence.

The 1900s: two markets and electricity

East Terrace at the beginning of the twentieth century continued to house Adelaide’s wealthy and notable citizens at its southern end. Henry Rymill, Harry Lockett Ayers and barrister Horace Vernon Rounsevell had been joined by shipowner William Hamilton and the university’s professor of mathematics and physics, William Henry Bragg (later knighted and a Nobel Prize winner). However, nearer to North Terrace significant changes were about to occur.

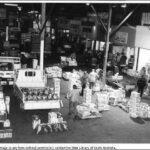

By the 1890s the East End Market had become congested and had difficulty accommodating the production from expanding market gardens on the Adelaide Plains and foothills and demand from a large city population. There was fierce competition for stalls and traders overflowed onto the streets.

In about 1900 William Charlick of Charlick Bros fruit, potato and grocery business, decided to ‘remedy the evils’ by building an extension to the existing market. However, negotiations for a co-operative venture with the East End Market Co. failed and Charlick determined to build a new market on land that he had purchased between Grenfell Street and Rundle Street. This site housed the tannery and Rookery, which were demolished prior to the construction of the market.

A company was formed to establish and manage the market: the directors included Charlick (chairman), J Vardon and TH Brooker (secretary). The project was enabled by the South Australian Parliament passing The Adelaide Fruit and Produce Exchange Act on 30 October 1903. The Act gave the company powers to erect the market and allowed the Adelaide City Council to pay out the owners and take over operations after a certain period of time.

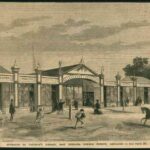

The foundation stone was laid by the governor on 24 April 1904 and the Adelaide Fruit and Produce Exchange, commonly referred to as the ‘New Market’, opened for business eight days later. Extensions were soon made along Vardon Avenue, Rundle Street, Grenfell Street and Union Street. The completed complex covered about 1½ha. HT Burgess reported at the time in the Cyclopedia of South Australia that there was room for ‘390 stands for vehicles and teams, 20 large packing stores, 16 shops, 11 small stores, 10 side stores, refreshment room, and shoeing forge’.

The architect for the Exchange was Henry J Cowell. His design featured decorative entrances with ornate gables and cornucopia motifs. The inscription over the Grenfell Street entrance reads, ‘The Earth is the Lord’s and the fulness [sic] thereof’ (Psalm 24:1). Shop fronts along the street frontages harmonised with the decorative design. Shops along East Terrace had verandas with carved ornamentation.

The Adelaide Fruit and Produce Exchange and East End Market continued to operate until 1988 when they were replaced by a wholesale produce market at the outer Adelaide suburb of Pooraka. The covered market areas of the Exchange were subsequently demolished to make way for residential developments. However, the original facades remain along East Terrace, Grenfell Street and Union Street.

Further accommodation was lost at the northern end of East Terrace with the electrification of Adelaide. The large-scale supply of electricity to Adelaide began in 1898, initially from a station at Port Adelaide. However, by 1907 all of the city was supplied from a power station constructed in 1901 by the Electric Lighting & Traction Co. on the southern corner of East Terrace and Grenfell Street. The Grenfell Street Power Station was followed by a converter station built facing East Terrace, between Grenfell Street and Pirie Street. The Metropolitan Tramways Trust Converter Station was constructed after 1906 in preparation for the shift from horse-drawn to electric trams. Designed by architects English & Soward, the converter station was described as one of the largest and most modern of its kind in Australia. The construction of the two stations reduced East Terrace housing north of Pirie Street to one line of two-storey terraces by 1910.

Changes in the south: East Terrace through the 1910s and 1920s

By 1915 a significant change in the residential character of East Terrace was becoming apparent. Remaining terraces and large homes were being converted into boarding houses. Through the 1920s these were joined by flats, as some of the wealthy moved out and their mansions were subdivided. The density of the residential population of East Terrace rose as single families or individuals were replaced by multiple occupants.

The use of some mansions also shifted from residential to education and health in the south. The Kindergarten Union of South Australia’s Kindergarten Training College under Miss Lillian De Lissa rented the large ‘Strathearn’ near South Terrace from 1913 to 1915. Parkwynd Private Hospital was located at no. 137 and St Mary’s Hostel for Girls was at no. 178 East Terrace from 1916 to 1972 (before becoming the Catholic Women’s League Child Care Centre from 1975 and then the CBC Community Children’s Centre from 2012).

On the initiative (and donations) of Lord Mayor John Glover, the Adelaide City Council improved services to the children of eastern Adelaide during the 1920s. A playground was constructed in Ityamaitpinna/Park 15 and opened by Governor-General Lord Forster on 11 September 1925.

Diversification in the 1960s

Through the Second World War and in the years following East Terrace retained the mixed residential and market characteristics apparent in the 1920s. The 1960s differed in that small businesses, health and education services took up premises south of Pirie Street and public facilities were created in Murlawirrapurka/Park 14.

East Terrace businesses were diverse and predominantly small-scale. They included insurance and property services, advertising and commercial artists, building services and accountants. Health organisations included the Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, the District & Bush Nursing Society, the Mental Health Services Day Hospital, Parkwynd Private Hospital and East Terrace Hospital. The South Australian Building & Furnishing Trade School and Christian Brothers College Junior School also operated on East Terrace, the latter built in 1963 was demolished and rebuilt to cater for more students with better facilities from 2011.

The City Council made significant improvements to Murlawirrapurka/Park 14 in the early 1960s. Following a tour overseas, Town Clerk William Veale proposed an artificial lake, playground and picnic area for this park. Work commenced in 1959–60 and the new facilities were opened by Lord Mayor John Glover in late 1960. The park was named Rymill Park to honour Lord Mayor Sir Arthur Rymill (1950–54) who had actively supported the extension and improvement of Adelaide’s parklands.

Artwork by Adelaide sculptor, John Dowie, in keeping with the area’s focus on children, was commissioned for the park. His ‘Piccanniny’ drinking fountain composed of an Aboriginal child moulded in coloured concrete, balancing a bronze water container, was placed on a white granite plinth by the playground. A sculpture of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ was unveiled on 17 December 1962. The National Rose Society of South Australia planted a rose garden in the southeastern corner in 1960.

Aboriginal associations

Pakapakanthi/Victoria Park/Park 16 was used by the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people as a camping and meeting ground during negotiations over land rights in 1980. Elders and others arrived in February of that year to confront the state government over a decision to open up their country to mineral exploration and to garner support. Negotiations with Premier David Tonkin and senior ministers led to the state’s Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act 1981 and the first grant of freehold title to Aboriginal communities in South Australia.

Return to residential: East Terrace from the 1980s

East Terrace came back into favour as a residential location from the late twentieth century. New town houses and terraces were built overlooking the parklands. Surviving mansions were renovated and re-occupied as private homes.

However, the physical environment for residents was very different from that of the nineteenth century. Regular horse races on Pakapakanthi/Victoria Park/Park 16 became less frequent and ultimately the South Australian Jockey Club left the park in 2007. Late in the twentieth century motor racing events were introduced to the area (the Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix from 1985 to 1995 and the V8 Supercars in the Sensational Adelaide 500/Clipsal 500 Adelaide from 1999), the Tour Down Under from 1999 and other cycling races, international horse trials and associated equestrian events, music concerts and festivals, fireworks displays and an open air service celebrated by Pope John Paul II during his visit in 1986 have altered the use of the area through mass participation activities. In 2008 the City Council began redeveloping Pakapakanthi/Victoria Park/Park 16 with a view to its greater use by the public.

Comments