Hindley Street is one of the 63 streets and squares laid out in Colonel William Light’s Plan of the City of Adelaide. It runs east–west, connecting King William Street and West Terrace. Hindley Street was named by a Street Naming Committee made up of the governor and 11 prominent colonists on 23 May 1837.

This street is named after Charles Hindley, a member of the House of Commons in the British Parliament. Hindley was an original director of the South Australian Co., which provided crucial financial support for the founding of the colony. He was also a director of the Union Bank of Australia. Charles Hindley never came to South Australia. He died in November 1857 following the consumption of 6 pints (3.4L) of brandy in 72 hours as prescribed by his doctor for an illness.

Buying up land on Hindley Street

Land in the city was divided into ‘town acres’, 16 of which lined both sides of Hindley Street. Light’s Plan as printed in 1840 suggests that the street quickly became a sought-after location, with all but one of these acres sold within four years of settlement. Nine acres were preliminary sales, made in the United Kingdom prior to colonisation. A further 22 acres were snapped up at an auction in the first months of European settlement. All sales were made without reference to the traditional owners of the land, the Kaurna people.

Early purchasers included people closely associated with the establishment of the colony. Emigration Agent John Brown bought acre 72. Brown went on to become a member of Adelaide’s first municipal council and a director of the South Australian Mining Association. Deputy Surveyor-General and, later, Chief Secretary Boyle Travers Finniss took up acre 78 close to King William Street. Cornelius Birdseye bought acre 55. He arrived on the Lady Mary Pelham in 1836 as overseer of South Australian Co. flocks and herds.

Several acres were purchased by newspaper proprietor Robert Thomas. In March 1837 Thomas took up residence on Hindley Street where he set up a general store, stationery and printing business. The first newspaper published in South Australia, the South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register, was printed on a Stanhope hand press at Thomas’s printing office on 3 June 1837. This press survives in the Historical Relics Collection of History SA.

At the auction in 1837 acre 51 was bought on behalf of an independent minister of religion, Thomas Playford. He and his family migrated to South Australia in 1844. The name of Playford became famous locally. Playford’s son, also Thomas Playford, was a state and federal politician. His long parliamentary service included two years as premier (June 1887–June 1889). Great-grandson Sir Thomas Playford remains the state’s longest serving premier with 26 years and 126 days in office from 1938 to 1965.

Early Hindley Street

By 1842 Hindley Street had the densest concentration of European settlement in Adelaide, particularly around the junction with Morphett Street and towards King William Street. George Strickland Kingston’s map of that year shows the emergence of side streets and laneways in subdivided acres. Significant buildings along the street included the Town Council Room, Robert Thomas’ printing office, the premises of John Woodford, a surgeon, the South Australian Club House, a Baptist Church and several company offices.

The South Australian Club was an association of gentlemen established on 4 August 1838. Objects of the association, as defined at a general meeting on 21 August 1838, included building a clubhouse in the city, furnishing it and ‘procuring by degrees’ a collection of books and maps. Members included the prominent colonists John Brown, James Hurtle Fisher, Thomas Gilbert, Colonel Light, John Morphett and Edward Stephens. Light, Morphett and Fisher were the trustees. In May 1839 the Victoria Hotel on Hindley Street was purchased as a temporary club house until the club moved to new premises on Hindley Street in the following February.

Seven hotels were constructed on Hindley Street in those first four years. One, the Buffalo’s Head, was owned by James Chittleborough who arrived in Adelaide on the Buffalo in December 1836. Chittleborough first operated licensed premises from a tent in Buffalo Row in the west parklands opposite the corner of North Terrace and West Terrace. Before being rebuilt in 1878, the Buffalo’s Head (Black Bull from 1841) was set back 9m from the footpath and surrounded by a picket fence and gate. The Berkeley Hotel stands on the site today.

The busiest street in town: 1860s–1880s

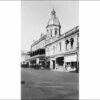

Hindley Street soon became the busiest street in town, with various shops, businesses and hotels crammed between King William Street and Morphett Street. Panoramas of Adelaide in the Australasian Sketcher in July 1875 and the Illustrated Sydney News in July 1876 show buildings in this part of the street to be largely two-storeyed with verandas over the footpath to protect people from the weather.

Single and two-storeyed homes were concentrated in the section between Morphett Street and West Terrace, although people also lived above shops and other small businesses. The number of households in Hindley Street increased from approximately 130 in 1875 to around 160 in 1885. The occupations of listed residents were overwhelmingly skilled trades and labouring related.

By 1860 there were 16 hotels on Hindley Street (roughly one hotel for every 70m). By the 1880s this number had increased to 18 (about one hotel for every 60m), giving this street the highest concentration of public houses in Adelaide. Eating establishments such as Mrs Vincent’s Refreshment Rooms, Bertha Schlemilch’s restaurant and WJ McCarthy’s Oyster Rooms also provided public refreshment from the 1870s.

Entertainment was available at the newly constructed Theatre Royal from 1868. Within ten years this popular music and theatre venue was too small to meet audience demand. It was rebuilt in 1878 to a design by George Johnson and served the community for the next 84 years. The interior of the theatre was built on three levels, with boxes on both sides of the stage. Patrons were strictly segregated: the pit and gallery were reached by a lane on the left of the building, the stalls through a narrow door on the front right-hand side and the dress circle via a wide entrance on the far right. Performers during the long life of the theatre included JC Williamson, Sarah Bernhardt, and Sir Lawrence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. Extensive alterations were made to the Theatre Royal’s interior in 1884 by Wright & Reed, and it was reconstructed again in 1913–14. The theatre was demolished by Miller Anderson & Co. in 1962 and replaced by a multi-level car park.

Textile, clothing and footwear establishments were well represented amongst the many small and medium sized businesses along Hindley Street in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1876 there were 25 drapers, tailors, boot and shoe makers and women’s outfitters on the street. Amongst these establishments was J Miller Anderson, which would develop into a leading South Australian emporium. Other small shops included jewellers and watchmakers, hairdressers, chemists and booksellers. Produce was supplied by butchers, fruiterers, greengrocers, confectioners and bakers.

Eight businesses operated by Chinese members of the community were clustered around the junction with Morphett Street: a fancy goods dealer, a merchant, a grocer, a tea importer and four cabinetmakers. Kaun Ti Temple, a Shenist temple, was located on the north side of Hindley Street, just west of Morphett Street. Known popularly as the Joss House, it served the spiritual needs of Adelaide’s Chinese population.

Also situated close to Morphett Street was the Labor League Hall (a precursor to Trades Hall in Grote Street). It housed the offices of the South Australian Tailors’ Society, the Bootmakers’ Union, the Railway Servants’ Society and the Engine Drivers’ Society. These unions all had members working nearby on North Terrace, Hindley Street and Rundle Street.

One large business dominated Hindley Street west at the end of the nineteenth century. The West End Brewery, established by William Clark in 1859, was designed as a model brewery. It replaced Morcom’s Temperance Hotel on acre 66. The brewery was taken over and consolidated in the 1860s by William Simms. By 1866 Simms was operating the brewery in partnership with Edgar Chapman. Simms and Chapman’s West End Brewery, with its distinctive tower chimney, is visible on the southern side of the street in the Illustrated Sydney News panorama.

In 1888 the West End Brewery was amalgamated with Edwin Smith’s Kent Town Brewery to form the South Australian Brewing Co. The brewery was beloved for its West End draught beer in particular. The custom of painting the chimney in the colours of the premiers and runners-up in the SA National Football League competition began in 1954. The brewery was demolished in 1982 two years after the company shifted its operations to its Southwark plant at Thebarton. The painting of the local football team’s colours continues there. That brewery is now known as West End, perpetuating the name of the Hindley Street brewery.

The changing character of Hindley Street: 1900–40

The nature of businesses along Hindley Street changed through the early years of the twentieth century. They gradually shifted from small retail outlets to larger firms and warehouses. Drapery and household furniture outlets such as Hoopers Furnishing Arcade, Federal Furnishing and WT Flint & Son remained a feature of the street. Larger clothing firms included Miller Anderson and Fletcher Jones.

The west end of Hindley Street deteriorated from the 1910s as both small businesses and residents left the area. Some larger production premises took their place, including printing works, paper bag manufacturers, Premier Knitting Works and C Rutherford & Co., wire mattress manufacturers.

Clustered around the Morphett Street junction in 1905 were 22 small Chinese businesses. Cabinetmakers, ‘fancy goods’ sellers, importers and hawkers predominated. Two Chinese laundries operated nearby. But by 1925 Adelaide’s Chinese population was in decline and businesses operated by the Chinese community were disappearing. By 1940 only a handful remained. The Joss House ceased to appear in Sands & McDougall’s Directory from 1900.

The east end of Hindley Street increasingly became a place to eat, drink and be entertained, although the form of sustenance and entertainment varied over time. The number of hotels fell, especially after 1908 with the abolition of barmaids and from 1916 with the introduction of 6 o’clock closing. By 1935 only ten hotels were left. One of these hotels is noteworthy: Tattersall’s Hotel, on the south side of Hindley Street near King William Street, was rebuilt by SA Brewing Co. in 1901–02 to a design by architects Garlick & Jackman. The hotel survives in the twenty-first century as one of the few heritage-listed buildings on Hindley Street.

While the number of hotels dwindled, saloons, tea rooms and cafes expanded. Offerings changed according to fashion. In the period from 1900 to 1910 dining rooms, fish and oyster saloons, wine saloons and tea rooms were popular. By 1925 cafes, including the Theatre Royal Café, Osborne’s Café and the Comino Café, had taken the place of dining rooms and most saloons.

The Grand Coffee Palace and Grant’s Coffee Palace, almost directly opposite each other, also featured in the early years of the twentieth century, and both have survived in other guises. Coffee palaces originated in the temperance movement of the closing decades of the nineteenth century, offering alternative refreshments to those in licensed hotels. As the new century progressed they operated more as places of cheap, respectable accommodation.

The Grand Coffee Palace erected in 1891 replaced a coffee palace on the site that was destroyed by fire in 1889. Rebuilt in 1907 and subsequently undergoing improvements internally, it is now the Plaza Hotel with local heritage status.

Grant’s Coffee Palace began as a group of 12 shops and dwellings erected in 1903 by German migrant, butcher and small goods manufacturer Leopold Conrad. The complex, named Austral Stores, was designed by his architect son, Albert Selmar Conrad, and built by WB Bland. The ornate design made extensive use of stuccoed dressings, brick and Marseilles tiles. Two three-storeyed decorated towers rose above a central balcony and veranda covered entranceway.

In 1908 the Adelaide City Council approved plans submitted by Jonathan Grant for dining rooms in a section of the complex that he had leased. His premises became known as Grant’s Coffee Palace. They were taken over in 1919 by John West and renamed West’s Coffee Palace. The ornate veranda and balcony were removed and shop fronts inserted in 1960, but the state heritage-listed building retained much of its original design into the twenty-first century.

Several theatres and other entertainment venues joined the Theatre Royal on Hindley Street east during this period. The Cyclorama, which showed scenes on a moving backdrop, was constructed at the turn of the century. The building’s façade, topped by a large domed tower and spire, dominated the streetscape. A year later it was converted to the Olympia Skating Rink. In 1908 the facility was leased and refitted as a picture theatre by West’s Pictures.

The Wondergraph Theatre was built by CH Martin to the design of Garlick & Jackman in 1912–13. It was also an imposing building, with two distinctive domes topped with high swan-necked lights each side of an ornate arched façade. The heyday of this theatre was in the 1930s. In 1940 its name was changed to the Civic Theatre. A further internal make-over occurred in 1957, when the Civic was renamed the State Theatre. It ceased to be a theatre by 1983.

The last theatre to be erected on Hindley Street before the Second World War was the Metro, built in 1939 to the design of Thomas W Lamb in association with F Kenneth Milne of Adelaide. Lamb was an American architect, noted as one of the foremost designers of theatres and cinemas in the twentieth century. The elegant interior was gutted and four cinemas built in its shell in 1975.

After the Second World War

Hindley Street ceased to be a significant retail street after 1945, although firms such as Miller Anderson and Fletcher Jones, together with several furniture emporiums, continued to attract customers. Its eastern end consolidated as a centre of entertainment, while the western section remained semi-industrial.

After the Second World War film rather than the stage became the primary focus of theatres. My Fair Lady Theatre was built specifically for the release of the film My Fair Lady in 1966. Companies such as British Empire Films and RKO Radio Pictures, an American film production and distribution company, also established outlets on the street. The range of entertainment expanded to include fun parlours in the early 1950s and cabaret, strip clubs and night clubs in the 1960s and 1970s. City Bowls and Ice Skating Adelaide provided recreational activity on the western end of the street.

Food and wine outlets diversified and grew in number from the 1950s as household incomes rose and eating out became accessible to a wide range of people. Cafes and milk bars remained popular while coffee lounges and restaurants flourished from the late 1960s. Food and drink on offer increasingly reflected post-war migration from southern and eastern Europe. Fish shops gave way to pizza houses and restaurants such as the Athens Restaurant and BBQ and the Paprika Club Restaurant. Flash Coffee Gelateria became an Adelaide institution, offering Italian-style gelati to appreciative customers.

Clubs and businesses established by European migrants replaced Chinese businesses near Morphett Street. By 1973 the Greek Club, the Cyprus Club, the Italian Reading Circle, the Panelinion Club and the Venezia Club were there. Greek and Italian businesses in particular operated from nearby premises. One of these, the Star Grocery, provided ‘continental’ foods to new arrivals and other appreciative customers.

Hindley Street in the twenty-first century

By the end of the twentieth century Hindley Street had developed a rather unsavoury reputation. Picture theatres had been replaced by more late-night nightclubs, strip clubs and bars. Tattoo parlours and billiard rooms, regarded with suspicion by many, operated alongside the few remaining down-market shops. Eating houses and restaurants continued to be well represented, although they were generally small and inexpensive.

As the twenty-first century unfolded, the state government, the Adelaide City Council and Hindley Street traders responded to the down-at-heel character of the street with various plans for changing its identity and atmosphere. The process has been led by the arts sector and education institutions. The South Australian Department for the Arts (Arts SA) tookup residence in the still beautiful West’s Coffee Palace, using its shop windows as exhibition spaces. The South Australian Symphony Orchestra and Youth Orchestras have occupied what was West’s Cinema.

Hindley Street west of Morphett Street is gradually being changed by the establishment and expansion of the University of South Australia’s City West campus. The buildings and the education services for students have reinvigorated this end of the street. The university has bought four of the nightclub premises with the aim of creating an environment that is safe for students and compatible with an educational hub. The process has benefited from similar arts and education facilities on the neighbouring North Terrace west, Currie Street and Light Square. Likewise, the completion of the new Royal Adelaide Hospital and related medical facilities on the parklands of North Terrace west will lead to a wider range of services on Hindley Street and redefine the street’s character.

Comments