There was hardly a family that was not affected by the death or injury of a loved one in the First World War. Communities across the state counted the cost. Almost 35 000 South Australians enlisted (a staggering 37.7% of the male population between 18 and 44 years of age) of whom 5511 were killed and 15 000 wounded. Their number included Aboriginal South Australians, who volunteered for service in spite of being subjected to discrimination in the country of their birth.

Instigation of the memorial

In response to this great sacrifice Premier Archibald Peake asked the South Australian Parliament to fund a memorial to those who had served and to their hard-won victory. In March 1919 his motion won the unanimous support of parliament. South Australia became the first state in Australia to resolve to build a memorial in relation to the First World War. It was to be named the National War Memorial, even though located in Adelaide. Two reasons proposed for this are that the name was chosen to emphasise the government’s intention that memorial should commemorate all who served, not just South Australians (Richardson, p1) and that it reflected the view, still held in the once separate Australian colonies despite federation, that the ‘province is a nation’ (Inglis & Brazier, p267).

Location and form

Both the form and location of the memorial were the subject of vigorous community debate over several years. Operatic soprano Dame Nellie Melba suggested ‘a clarion of bells’. Pastoralist, author and politician Simpson Newland argued that Bay Road between Adelaide and Glenelg (Anzac Highway from 1924) should be turned into a ‘Way of Honour’ with triumphal arches at each end. Prominent Adelaide builder Walter Charles Torode proposed a 30m-high metal and marble monument on Mount Lofty, with an electric car to carry people to the summit. A survey of prominent architects selected Montefiore Hill as their preferred location. Victoria Square, the grounds of Government House and the Torrens Parade Ground were all put forward as suitable sites.

A significant focus of discussion centred on Government House and the role of the governor. Left-wing politicians and republicans argued that the grounds should be taken over by the state and used for the memorial. Conservative politicians opposed such a move. The National War Memorial Committee was prepared to accept the use of Government House grounds, but delayed any announcement. Legal issues led to a compromise. It was decided that the memorial would be situated on a corner of Government House grounds ceded for the purpose.

The design of the memorial was finally determined through two architectural competitions.

The 1924 competition

The first design competition was initiated in February 1924. The preamble to the conditions of entry set out the committee’s vision for the monument. It was to ‘perpetually commemorat[e] the Victory achieved in the Great War, 1914-1918, the Supreme and personal sacrifice of those who participated in that War, and the national effort involved in such activities’ (cited in Wikipedia). The location was set at the entrance to Government House on the corner of King William Street and North Terrace, just north of the South African War Memorial. Entries were limited to South Australians who were also British subjects.

An assessment panel was formed to judge the 26 designs submitted. However, before judging could be completed all submissions were lost in a fire at the Richards Building in Currie Street, Adelaide on 11 November 1924.

The 1926 competition

Pressure from servicemen led to a second design competition in 1926. Entries were again limited to South Australian British subjects. A new site was selected – up to 0.2ha excised from Government House grounds on the corner of North Terrace and Kintore Avenue. A total of 18 entries were judged by Australia’s Chief Architect John Smith Murdoch.

The winning design

The winning entry, selected on 15 January 1927, was submitted by the South Australian architectural firm of Woods, Bagot, Jory & Laybourne-Smith. The actual design was by Louis Laybourne-Smith, building on the 1924 design of his colleague Walter Bagot. The assessor commented that the winning architect ‘depends almost entirely on the sculpture to tell the story of the memorial, employing in his design no more architecture than that required to successfully frame and set his sculptural subjects, and to provide accommodation to the extent asked for by the conditions’ (cited in Wikipedia).

The proposed monument had two distinct sides, each featuring a relief carved from Angaston white marble framed by a rough-hewn arch of grey Macclesfield marble. The relief and accompanying bronze statuary on the obverse side, facing the street corner, represented the prologue to war. The reverse side represented the aftermath. Steps leading up to the raised statuary and reliefs were of Harcourt granite. Construction materials were chosen to harmonise with Parliament House. The monument was orientated on the same axis as both the Womens Memorial Cross of Sacrifice and St Peters Cathedral to the north and placed back from the streets to allow for public gatherings. The orientation permitted the dawn sun to fall on the eastern façade.

Realisation by George Rayner Hoff

Sydney sculptor George Rayner Hoff (1894-1937) was commissioned to realise the reliefs and bronze statuary in detail. Hoff was born on the Isle of Man in 1894 and completed training first as a stonemason and then at Nottingham and London Art Schools. He moved to Sydney in 1923 to head the Technical College, where he established a highly regarded School of Sculpture. He produced works for several war memorials, including the Dubbo War Memorial and the Anzac Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park. His memorial sculpture was frequently challenging and controversial, eschewing heroic images of war.

Hoff produced the detailed designs for the Adelaide War Memorial from his Sydney studio. He brought a very different style to the heavy winged stone figures of the reliefs as sketched by Bagot. Hoff’s Art Deco winged spirits are lighter and more stylised, but still powerful. They hover imposingly above the realistic statuary below.

Construction

Construction began in 1928 with the cutting and placement of the large marble blocks from Angaston and Macclesfield. The work was undertaken by South Australian Monumental Works, supervised by monumental mason Alan Tillett.

A strike by the stone masons soon led to delay. The workers demanded a 44-hour week and payment at ‘outside rates’, considering that much of the job was not under cover. However, Tillett’s tender only provided for lower ‘inside rates’ and a 48-hour week. Tillett won the dispute in court, but several stone masons left and the damage to the firm forced it into receivership, where it remained until the memorial was completed.

An Adelaide firm, AW Dobbie & Co., made the bronze castings of the sculptures. The two relief figures were produced by Julius Henschke from one-third size plaster models by Hoff.

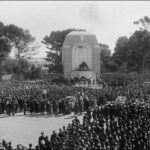

Unveiling

The memorial was unveiled by Governor Sir Alexander Hore-Ruthven VC, DSO on Anzac Day in 1931 before a vast crowd, with an estimated 75 000 people attending Anzac Day processions and events. Many unable to be accommodated at the site waited at the Cross of Sacrifice for the Anzac Memorial Service that followed. Other spectators clambered over the statue of King Edward VII to get a vantage point. Ex-servicemen, scouts, guides, wolf cubs and brownies provided an honour guard. The proceedings were broadcast on Radio 5CL for those unable to attend.

The governor was a retired brigadier-general who had been wounded at Gallipoli in 1915. He had been awarded the Victoria Cross in 1889 while attached to the Egyptian Army. In his speech, the governor expressed the hope that the memorial would inspire those who followed ‘to devise some better means to settle international disputes other than by international slaughter’ (Mail, p2).

The completed memorial

No soldier is depicted in Adelaide’s War Memorial, but the impact of the war on all South Australians is conveyed with great intensity.

On the obverse face the arched marble relief facing North Terrace shows the Spirit of Duty holding an unsheathed sword upright as a cross, calling young men and women in a prologue to war and sacrifice. The bronze figures of a farmer, scholar and young woman cast aside the symbols of their civilian lives as they respond to duty. The inscription reads, ‘To perpetuate the courage, loyalty, and sacrifice of those who served in the Great War 1914-1918’.

On the reverse face the marble relief on the northern side depicts the aftermath of war. A winged figure variously described as the Spirit of Womanhood and Spirit of Compassion carrying a sheathed sword, sadly bears away a dead youth, symbolising sacrificed sons and lovers. Beneath the winged spirit, water falls from the mouth of a crowned, bronze imperial lion into a pool below. The continuous flow signifies the endless flow of memories of the fallen. The inscription by English poet John Oxenham (William Arthur Dunkerley) reads, ‘All honour give to those who, nobly striving, nobly fell that we might live’.

The memorial houses a domed inner shrine or record room, which can be entered via a doorway on each side. Bronze panels inscribed with the names of those who died in the war line the walls. The honour rolls list names under their serving battalions. A valedictory is inscribed above: ‘Their glory survives in everlasting remembrance. Not graven in stone but enshrined for all time in the hearts of man’.

Restoration work

The memorial underwent remediation work in time for Remembrance Day services in 2001. Bronze and stonework details were conserved and the foundations were reinforced. Architects Bruce Harry & Associates were awarded the 2002 Heritage Medal by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects for the work.

Additions to the site

The First World War was not ‘the war to end all wars’ as had been hoped. Smaller memorials commemorating later conflicts and the contributions of particular units have been added to the site. Six simple wooden ‘Crosses of War’ commemorating the 10th, 27th, 48th and 50th battalions of 1916, the Siege of Tobruk (1941; a John Dowie artwork) and the Royal Australian Regiment are on the walls of Government Domain. Other memorials relate to the Battle of Lone Pine (6-9 August 1915), those who died in France during the two world wars, the 8th Division (1940-45) in the Second World War (1939-45), the Malayan Emergency (1948-60, 1964-65), the Korean War (1950-54), the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation in Borneo (1962-66) and Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War (1962-73). An honour roll, listing South Australians who died in the Second World War stands on the site also.

Comments

2 responses to “War Memorial”

good afternoon, I was visiting a war memorial at Ucolta in South Australia on the weekend, and noted the names on the WW1 memorial are nearly all faded or become impossible to read. What can be done to restore the memorial?

Hi Bernice,

I would start by contacting the local council, which in this case is the District Council of Peterborough. You might also try contacting the Office of Australian War Graves (OAWG) – https://www.dva.gov.au/recognition/office-australian-war-graves/care-war…