Although Aborigines had long fashioned stone into implements and there was extensive trade in ochre, South Australia’s modern mining tradition began in 1836 when the South Australian Company appointed a geologist to look for water, coal, minerals, building stone and limestone.

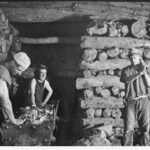

Early mining

Australia’s first metal mine, Wheal Gawler (1841) produced Australia’s first mineral exports of silver and lead. Copper was king in the following decades, with spectacular successes at Kapunda (1842–1878) and Burra (1845–1877) in the Mid North and Moonta–Wallaroo (1860–1923) on Yorke Peninsula. The ‘Monster Mine’ at Burra, for a time the richest copper mine in the world, was the first metalliferous mineral mine in Australia to pay dividends. Other significant Australian firsts include the discovery of opal (1839), a company mining town (Burra, 1845), a gold mine (Montacute, 1846), an official government geological report and geological book published in Australia (T Burr, Remarks on the Geology and Mineralogy of South Australia, 1846), a mining strike (Burra, 1848–49), drilling for oil (at Salt Creek on the Coorong, 1881–83) and the discovery of uranium (1890).

Mining attracted Cornish, Welsh and German miners. Cornish practices and equipment were widely adopted. Mechanical methods and machinery (such as Cornish beam engines) were introduced as soon as they became available; local manufacture generated engineering enterprises such as that of James Martin of Gawler. South Australia’s first smelter, established in 1845 at Hindmarsh, treated Glen Osmond’s silver–lead ore. From February 1852 a government assay office assayed and smelted gold mined in the eastern colonies for local currency. Many smaller workings and short-lived mining operations scattered throughout the Adelaide Hills and Flinders Ranges produced copper, gold, silver, lead and zinc. The first chief inspector of mines was appointed in 1861. Discoveries of gold in the latter part of the 1860s at Echunga in the Adelaide Hills and the Barossa Range led to the creation of a warden of goldfields office in 1868. Gold discoveries in the Northern Territory between 1871 and 1873 also required a government presence.

Sharing the mineral wealth

From the 1860s a belief that mineral wealth belonged to all slowly emerged. Private enterprise was initially relied on to locate and develop mineral resources, while the crown retained control over gold and silver only. In 1882 the government Geological Survey of South Australia was formed to search for payable mineral deposits and water supplies.

Private enterprise, rather than developing mineral resources, resorted to investment and speculation within and outside the colony by the 1880s. Given the availability of gold and other rich mineral deposits elsewhere, South Australia often lost skilled miners and investment capital: there was much ‘mining on the Exchange’, with the workings of the major silver–lead–zinc deposits at Broken Hill (New South Wales, 1883) and gold at Kalgoorlie (Western Australia, 1893) being aided by the local stock market.

With general acceptance that mineral wealth was public property rather than belonging to any sectional interest group, parliament legislated in 1886 and 1888 to alienate mineral rights to the crown. As public ownership over minerals was asserted, private enterprise sought more government assistance. After a royal commission, the Mining Act (1893) established a consolidated body to regulate and encourage the industry. The Department of Mines formally came into being in 1894. Assistance to the mining and quarrying industries was soon to include financial subsidies, rewards for discoveries, provision of support facilities such as drills and batteries, the selection of sites and inspection of mines and quarries.

Increasing Government involvment

By exerting such direct involvement in the industry, successive governments had to frame policies for the development of mineral resources. World War I and its aftermath led to a diversification of interests: some of the new-found Coober Pedy opal was introduced to the world market; gypsum, limestone and dolomite deposits provided supplies for plaster, chemical, cement and steel industries; salt was produced for an alkali works; companies mined and treated radioactive ores; potential water supplies and reservoir sites were examined, and exploration for petroleum became increasingly important. Iron ore mining by the Broken Hill Proprietary Co. Ltd (BHP) at Iron Knob in the Middleback Range from 1899 led to the development of Whyalla on Eyre Peninsula as an industrial city and the rise of Port Pirie in the Mid North was directly connected to the mines at Broken Hill; Port Pirie still has the world’s largest lead smelter.

One of Premier Tom Playford’s earliest initiatives was to ensure that South Australia became self-sufficient in energy resources. The search for coal at Leigh Creek in the Far North commenced in 1890, resumed in 1941, and the first dragline operations began in 1943. The town which housed Leigh Creek’s workers was the first of Australia’s modern mining towns. The Electricity Trust of South Australia (ETSA) took over administration of the coalfield early in 1948 and then constructed the Port Augusta Power Station complex to utilise Leigh Creek coal.

Uranium mining comes to the fore

Beginning in 1906 at Mount Painter in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia developed a uranium industry; from 1954 until 1961 Radium Hill (south-west of Broken Hill) supplied uranium for the American, British and Australian governments. The project’s demise coincided with a general revitalisation of private sector interest in mineral exploration. Copper mines opened at Burra, Kanmantoo in the Adelaide Hills and in the Pernatty Lagoon/Mount Gunson area north-west of Port Augusta in 1970. Other significant mineral discoveries included uranium at Beverley (west of Lake Frome, 1969) and Honeymoon (north of Radium Hill, 1972) and lead–zinc at Puttapa in the Flinders Ranges, where mining began in 1970.

The industry was increasingly challenged on environmental issues. In the late 1970s BHP ceased piping noxious wastes from its Whyalla operations into the waters of upper Spencer Gulf. Attempts to clean up the Bremer River and underground catchment areas badly polluted by the Nairne pyrites mine were less successful. By the late 1970s changes in world health standards suggested serious health and environmental problems may have resulted from the proximity of lead smelters to Port Pirie. Public concern over the disposal of radioactive waste from the former uranium treatment plant and the health of the town’s population, especially high blood lead levels among children, resulted in a ten-year lead monitoring program from 1984. Similar concerns accompanied the development of the massive Olympic Dam copper–uranium–gold–silver–lead deposits on Roxby Downs Station in the Far North following its discovery in 1975. The stormy passage of the Roxby Downs Indenture Act (1982) through state parliament was indicative of the depth of feeling over this major mine of world importance.

In the 1990s innovative geological concepts allied with remote sensing, powerful computers, image processing, enhanced radar, seismic, electrical and electromagnetic geophysical techniques have guided mineral exploration. Government support for these initiatives reflects the expectation that wealth won from the recovery and processing of minerals and petroleum will continue to provide employment and economic benefits.

Comments