Although Kangaroo Island is only 15km from mainland South Australia, the dangerous waters of Backstairs Passage have acted as a physical and psychological barrier to its small population. Struggling to survive in the comparative isolation of a difficult environment, islanders have developed a persistent sense of difference from other South Australians.

The locality

The third largest of Australia’s islands, Kangaroo Island lies across the entrance to Gulf St Vincent, obstructing the sea lanes to Adelaide. The island is 155km long and an average 50km wide, tilted slightly from north to south with a steep northern coast, a less steep but equally rugged southern coast, and a broad, infertile ironstone plateau between, 300m at its highest. Dense mallee scrub is interspersed with bulloak, broom bush, banksia shrubs and yacca. Annual rainfall varies from 500mm in the east to more than 900mm in the highest region.

The earliest inhabitants

Uninhabited at the time of European contact, evidence of an extinct island race remains and in the legends of the Ngarrindjeri (including those in the Tangane language group) the island is Karta, the Island of the Dead. Archaeological discoveries and artefact interpretation of pre- and post-colonial periods continue today.

Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin explored the coast in 1802–03, Baudin giving French names to many points as he circumnavigated the island. Following the explorers’ reports of large numbers of seals on surrounding islets, in the early nineteenth century sealers and runaway sailors brought Tasmanian Aboriginal women to the island to help gather skins and salt for trade. Some descendants of these people live still in South Australia.

Three unofficial colonists preceded settlement by the South Australian Co. in July 1836: ‘Governor’ Henry Wallen (or Wallan) in the Cygnet Valley in 1818, George ‘Fireball’ Bates at Hog Bay in 1824 and Nathaniel Walles (Nat) Thomas at Creek Bay in 1827. When the company’s whaling venture failed and lack of fresh water was a growing problem, Colonel William Light moved the site of the official settlement to Holdfast Bay on the mainland. Coastal cutters brought supplies and communication to the remaining small population. Increasing intercolonial shipping necessitated lighthouses at Cape Willoughby (1852), Cape Borda (1858) and Cape St Albans (1908) to assist navigation through Backstairs Passage.

Tenuous developments

Because of the remote and unyielding conditions pastoralism failed. Surveying of the Hundreds of Dudley (1874) and Menzies (1878) opened the land to small-scale barley and oats farming. In 1876 the telegraph cable from Kingscote to Cape Borda provided a communication link with the rest of the world. From the proclamation of the District Councils of Kingscote and Dudley in 1888 islanders have depended on the South Australian government for projects such as jetties and for the means to extend roads and other services. A railway across the island’s backbone to carry produce to its port was considered by a Royal Commission over 1908–11 but was not introduced by the government.

Prospectors did not find mineral wealth but islanders gathered resin from the yacca (grass tree) to export to English and European ammunition, varnish and polishing wax factories. The production of eucalyptus oil from the narrow-leafed mallee (Eucalyptus cneorifolia) was once a profitable industry and still provides interest for tourists. Ligurian bees, introduced by South Australia’s Chamber of Manufactures in 1884, produce high-quality honey, and are exported throughout the world. Kangaroo Island was legislated as an asylum for the breed in 1885. Early in the twentieth century commercial interests harvested superior salt near American River until the deposit was exhausted. After 1960 the underlying gypsum was mined and shipped from Ballast Head.

Arrested development

From 1906 to 1910 the island experienced a minor land boom. New land legislation, and proclamation and survey of new hundreds expedited closer settlement, despite the infertile soils. The island’s first newspaper, the Kangaroo Island Courier (established in 1907), reported on some of these developments. After the Second World War the state government selected 250 000 acres (101 171ha) of the ironstone plateau, one-third of Kangaroo Island, for a soldier settlement scheme. At Parndana the 174 returned servicemen faced a tremendous challenge. Support from the Commonwealth government enabled the large-scale application of scientific knowledge; the addition of trace elements combined with superphosphate and subterranean clover finally rendered fertile land that had hitherto defied all attempts at farming. The island’s population increased from 1479 in 1947 to 2522 in 1954, and at the 2011 census was 4417.

Protecting nature

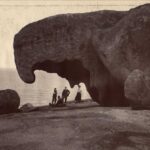

Not all the land could be turned over to farming. After a 27-year advocacy campaign, and periodic dedication of land by the government, in October 1919 the South Australian parliament established Flinders Chase as a nature reserve on the western end of the island. Flinders Chase provides a protected environment for the island’s unique flora and fauna and a sanctuary for mainland species threatened with extinction. Indeed, 18 adult koalas from French Island, Victoria, relocated there in the 1920s adapted so well that, without any predators, numbers increased alarmingly. To protect the habitat a controversial management program involving sterilisation of over 2500 koalas began in 1997. Flinders Chase has become a valuable ‘ecological laboratory’ and, like the scientific work carried out since 1979 at Pelican Lagoon Research and Wildlife Centre, it has international significance.

Slow growth

Over the years several industries were suggested: tobacco growing, wool processing, hops cultivation, flax crops for linseed fodder, china stone and clay mining (successful over 1905–10) and, before scientific agronomy brought successes, two-thirds of the island was proposed for development as a commercial timber plantation (1917). The first Kangaroo Island agricultural show was held in November 1911.

Air travel and high-speed ferry services have eased the isolation, while a submarine cable laid in 1965 supplies electric power. Penneshaw hosts a reverse-osmosis seawater desalination plant installed in 1998. The 1991 economic slump forced farmers to diversify. Many now produce specialty sheep cheese, honey, eucalyptus oil and marron for export, and vineyards, olive plantations and forestry are more or less promising ventures. Kangaroo Island has become a leading ecotourism destination for international visitors.

Comments

6 responses to “Kangaroo Island”

If the photo you’ve used at the head of your homepage is of the early Penneshaw Jetty with a trading ship standing off, with what I knew as “Ironstone Head” a backdrop, then may I suggest the image has been reversed. Fortunately, it will be easy to correct, as it may need to be. I’ve known the area, my mother’s home, since childhood.

Yours sincerely

Philip Sjostrom

Hi Philip,

Good eye! You are correct in stating that the early jetty pictured is at Penneshaw instead of American River, and it turns out that the original glass negative image in our archival collections was scanned in reverse. We have now corrected both the image and caption, and have even narrowed down the date of the photograph to a specific year (1903).

Hi and thank-you, James.

It’s nice to see kangaroo Island pointing in the right direction, again.

The ship anchored near the Hog Bay jetty may be “BRINAWARR” (1890-1918). If not, then it’s a very close relative, almost certainly out of the same shipyard or by same designer. It’s no fluke they look so similar. The ship’s profile in both photographs are very similar and it is entirely possible that a couple of slight differences in the superstructure, as seen in the two photos could be explained by the fact that ships were very often modified greatly over their service life. (Nelcebee is a great example of that – started life as a steamship, ended as a ketch with a diesel auxilliary). The date of the photo of Hog Bay, 1903 is neatly right in the middle of Brinawarr’s years of service. HOWEVER there’s something very perplexing about the connection between the photo labeled “Brinawarr” (your link, here which is captioned as Brinawarr http://www.flotilla-australia.com/images/brinawarr-slv.jpg )

…. and the text supposedly associated with the ship in the photo.

“BRINAWARR 119 gross tons, 73 net. Lbd: 91’2″ x 18’4″ x 7’5”. Wooden steamship built by J Hawken Snr, of Coolangatta, at Shoalhaven New South Wales. (Strange that Coolangatta Queensland on the Tweed River, border of New South Wales and Shoalhaven, well south of that locale are stated as the construction site. Could well be constructed on the Tweed River, Coolangatta and serviced the Shoalhaven district for J Hay,whilst registered at Sydney.) How J Hay employed this vessel is unknown however her dimensions state river work only. October 1893 acquired by the Adelaide Steamship Co and employed as a tender on the Pioneer River, Mackay, Queensland. Sank when span of a bridge collapsed on her during a Cyclone in January 1918. Not salvaged (Brinawarr- Aboriginal word for ‘Place of water lilies’)

So, Brinawarr (or “Brinawarr”) was supposedly designed “for river work only”, but perhaps some-one has made a mistake because the ship at Hog Bay IS, if not the same ship, then one of near identical design, yet Backstairs Passage is decidely not a quiet river, as I’ve found a few times, aboard my uncle’s cutter, the “Snoz”. Interestingly, the text says Brinawarr’s working life was largely unknown but it is known that she was bought, in 1893, from the original owner, by Adelaide Steamship Company, so Brinawarr or her twin quite likely did of opportunity & motive to be at Hog Bay in 1903. The “river-work only” statement may be a legacy of some confusion, by someone, at some stage which sadly happens so often with history, when errors suddenly appear as facts. The ship (or ships) in both photos look pretty seaworthy to me & not very riverboaty. I fail to see how “her dimensions state river work only” – that statement doesn’t fit the photo.

Anyway, that’s what I think. Here’s the page where I found the text regarding “Brinawarr” http://www.flotilla-australia.com/adsteam.htm#brinawarr-adsteam

Those old coastal steamers’ stories can be quite fascinating. If you have time, you may be able to correct a small item in SA’s history.

Yours sincerely, Philip Sjostrom.

Hi, James, again, sorry! I’ve now had a much closer look at the two ships I was rattling on about, and have concluded they are likely not the same vessel, even though very similar in profile, especially since ship designs varied from one build to the next & were very often each ship was a unique design. I’d be very interested if you do find anything more about the ship in the Hog Bay photo. If it’s not Brinawarr, then the ship at Penneshaw would likely be mentioned somewhere else in SA maritime archives. Without a photo, though ….

Thankyou for your help,

Phil Sjöström

Nuriootpa

Hi. I lived on Kangaroo Island when I was young – for about 2 1/2 Years.

I assume in the mid 60’s.

Where I lived was a farm (crops, cattle and sheep) Close proximity to snug cove and kangaroo beach.

Do you have any historical data on it? All I can find is the resort there now.

Hi Susan,

We don’t hold anything like that in our collection, but you might be able to find what you’re looking for through this State Library guide to archival maps of South Australia – http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/site/page.cfm?u=691