From churches to used car yards, Flinders Street has reflected changes in the city’s character. It has never been a main thoroughfare, but rather an affordable location for early residents and later small businesses.

Flinders Street was one of the 63 streets in Colonel William Light’s Plan of Adelaide named by a Street Naming Committee of prominent colonists on 23 May 1837. It acknowledges Captain Matthew Flinders who, as commander of the Investigator, conducted the first detailed survey of the South Australian coast. On the same voyage (1801–03) his ship completed the first circumnavigation of Australia.

Street of churches: 1860s and 1870s

Away from the initial settlement in the northwest corner of the city, Flinders Street was slow to develop. George Kingston’s map of 1842 shows few buildings. By 1865, when Townsend Duryea photographed his panorama of Adelaide from the tower of the Town Hall, construction was evident, but of a limited kind.

Churches dominated the street in the 1860s and 1870s. They reflected the diversity of Christian denominations represented in the colony, being erected by Anglican, Baptist, Presbyterian, Congregational and Lutheran communities. Religious groups outside the established Anglican Church had been active in the planning of the colony of South Australia in the United Kingdom in the 1830s. They formed a substantial proportion of the population of early settlers.

One of the first churches was St Paul’s Anglican Church built on the corner of Flinders Street and Pulteney Street in 1863. A rectory facing Flinders Street was added shortly after. The congregation of this High Anglican Church included prominent Adelaide families. Henry Ayers worshipped there as did members of the Bonython, Schomburgk, Everard and Bray families. St Paul’s was deconsecrated in 1983 and its Tiffany stained glass windows, donated by Henry Ayers’ daughter, Lucy, relocated to Pulteney Grammar School on South Terrace.

Closer to Victoria Square, Flinders Street Baptist Church opened on 26 April 1863. This church symbolised the consolidation of a previously divided Baptist community in Adelaide under the leadership of the young and dynamic Reverend Silas Mead. Mead was instrumental in the erection of the church between 1861 and 1863, the hall (opened 1870) and the manse (opened 1877). The church is noteworthy for the fine detail of the façade and exquisitely carved stone capitals on the porch pillars.

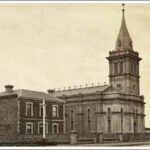

A Presbyterian Church was constructed across the road from the Baptist Church. Its severe façade was lightened by the addition of an elegant spire in 1865. A manse was built next door in the same year. In 1929 this church amalgamated with Chalmers Presbyterian Church on North Terrace to form Scots Church, North Terrace. The Flinders Street property was sold in 1956 and the church was demolished the following year.

Also close to Victoria Square, Stow Memorial Church was erected in 1865–67 as a memorial to Reverend Thomas Quinton Stow. Stow, the first Congregational Minister in the colony, preached his first sermon on 5 November 1837 on the southern side of the River Torrens, near the present Morphett Street Bridge. He was associated with the first Congregational Church building in Adelaide (in Freeman Street, now part of Gawler Place) and the beginnings of higher education in the colony. Stow Memorial Church was renamed Pilgrim Church in 1977.

A large manse was constructed alongside Stow Memorial Church in 1869. Substantial additions were made in 1877 and in the 1920s. Early in the twentieth century the entire building was encased in a colonnaded façade in the Italianate style that can be seen today. Sold by the church in 1901, the one-time manse has housed a sanatorium, the government’s Registry Office and the Ethic Affairs Commission.

The other major church built on Flinders Street was the Evangelical Lutheran Bethlehem Church. Opened on 23 June 1872, this church is associated with the German migrant community. Its bell tower was intended to house three bells. The bells were reputedly cast in Germany from cannons captured from the French and presented by Prince Bismarck on behalf of the emperor. Two alternative explanations as to why these bells were not installed are that the ship carrying the bells was lost and that they arrived in Sydney in 1879 and were exhibited at the Sydney International Exhibition where they won a first prize. Regardless, they never reached their destination in Adelaide (Marsden, Stark & Sumerling, p136; State Library of South Australia B1937).

Living on Flinders

Poorer residents occupied premises along Flinders Street, away from Victoria Square. Early cottages and terraces were predominantly single storey and very small. Many had wood shingle roofs and rough-cut wood paling fences. By the end of the nineteenth century corrugated iron roofs and verandas were common. Some cottages occupied land sufficient to grow vegetables and fruit trees. Children played on the small plots of land and on the dirt road outside their homes.

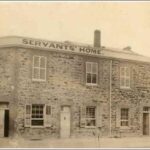

An atypical larger residence was the Servants’ Home, built mid century by the government on the corner of Flinders Street and Freeman Street (now Gawler Place). This two-storey establishment provided food and shelter for newly arrived migrants, especially young women straight off the boat, until they could find work. In 1863 the home’s management committee stated its aims:

The Adelaide Servants’ Home is designed as a temporary abode for those of every creed and country, when out of place, or convalescent from the Hospital, or newly arrived in the colony, who possess a good character for respectability and fitness for their duties. It will afford them the protection and comfort of a plain well-ordered home, and through the registry to be kept, bring them into contact with respectable employers only.

Demand for accommodation at the home led to overcrowding and insanitary conditions. Additions were made to the front and rear of the premises in 1877; a washhouse was constructed, sanitation was improved and the attached yard was drained and paved with flagstones.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century more substantial villas featuring wrought iron decoration, striped corrugated iron verandas and ornamental gardens began to be built on Flinders Street for wealthier families. Building contractor Richard Verco and carpenter/builder George Langdon Bonython occupied classic Adelaide villas on Flinders Street.

Workers’ cottages also featured a little wrought iron decoration on the edging of their verandas by the turn of the century. However, by the 1920s homes were being demolished in favour of expanding industry. Remaining residences were allowed to deteriorate. Families hung on in poor quality accommodation surrounded by small-scale factories and businesses. By the 1960s most homes on Flinders Street had been either demolished or taken over by industry.

Observatory House

One elegant building that survived the successive demolitions and rebuilding of the twentieth century was Otto Boettger’s Observatory House. Boettger was born in Germany in 1842. He was apprenticed to an instrument maker and became the foreman of a firm in St Petersburg, Russia. He also worked in Hamburg as an astronomer’s apprentice before migrating to South Australia in 1877. In Adelaide he established a successful business manufacturing and repairing scientific instruments. Boettger lived next door to the site of Observatory House from about 1879 until it was built for him in 1906.

Although small, Observatory House stands out. Its look-out tower, tiled roof and detailing create a distinctive and attractive building. Observatory House is heritage listed.

Education

Prior to 1875, when primary education was made compulsory in South Australia, most education services were provided by schools run by individual women or by churches. Flinders Street housed several such establishments.

Foremost amongst these was St Paul’s Day School for the Poor, which was constructed in 1872–73 on the south side of Flinders Street, near Hutt Street. Designed by architect EJ Woods, Flinders Hall, as it became known, was intended to have a spire, but limited funds meant that was never built. Alterations were made to the two-storey building in 1891 and the schoolroom extended in 1896. It continued to operate as a school in the twentieth century. The building was sold in 1950.

The Lutheran Church’s Martin Luther School operated into the twentieth century in Flinders Street. Images show a basic, cramped facility in which children of the poor are well represented.

A school for older girls run by a local, Miss Martin, was at 110 and 114 Flinders Street between 1906 and 1918. Opposite on the south side of the street was the Adelaide Shorthand and Business Training Academy, which began in the 1890s.

Following the Education Act 1875, the government became more directly involved in the provision of education. Several ‘Model Schools’ were soon constructed in the city. Governor Sir William Jervois opened the ‘City Model School’, Flinders Street Public School, on 22 November 1878. The large bluestone buildings designed by EJ Woods were intended to house about 800 students. The school continued to function as a primary school until 1969, when it became the Flinders Street Adult Education Centre. In 1978 it became the Adelaide College of Further Education, School of Music. In 2012 the restored heritage-listed building housed the Baha’i Centre of Learning.

The Department of Education constructed its headquarters at 31 Flinders Street on the southwest corner with Gawler Place in 1912. This seven-storey building of ashlar masonry featured an entrance framed by Doric columns and surmounted by the Australian coat of arms. Other government departments were based in the building too. Despite protests, it was demolished in 1973. Larger premises for the greatly expanded Education Department were constructed there: it is now occupied by the Department of Education and Child Development which includes Families SA.

Business and motoring

Small businesses and factories gradually took up premises in Flinders Street. The first businesses were dominated by the construction trades required by a growing town: builders, masons and timber merchants, followed by plumbers, gasfitters and iron merchants. In amongst these enterprises were a sprinkling of shops and hotels serving residents and workers. One noteworthy shop was that of accomplished photographer Captain Samuel Sweet. His photographs of Adelaide in the 1870s and 1880s provide an invaluable record of the city and surrounds.

By the second decade of the twentieth century the rapidly increasing number and type of businesses along Flinders Street reflected the growth of the motor industry in South Australia and the take up of various forms of motor transport by the public. Car sale rooms first appeared, followed by garages and service premises for motor bikes and side cars. A driving school was established. Mechanics advertised their services and by the 1920s Frank Warden’s tyre and tube service station was in business. In 1939 the Radio Corporation, selling, installing and servicing car radios was operating near Gawler Place.

New and used car sales, service and repair businesses and garages continued to be well represented on Flinders Street until the 1980s when they began to shift to busier arterial roads. The last car showroom closed in the first decade of the twenty-first century and today just a tyre centre remains.

Comments