Wirrarninthi/Park 23 is part of the parklands which Colonel William Light placed around the City of Adelaide in his plan of 1837. It is bordered by West Terrace on its east side, Sir Donald Bradman Drive (previously Hilton Road) to the north, Anzac Highway (previously Bay Road) to the south and railway lines to the west. West Terrace Cemetery has subsumed a large central portion of this park, with only a small section surviving on the cemetery’s south side.

The traditional owners of Wirrarninthi/Park 23 are the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains. In 1997 the Adelaide City Council signed a reconciliation statement that recognised prior occupation of the city site by the Kaurna and committed the council to recognising their heritage. The council resolved to give its parklands and squares Kaurna names in consultation with appropriate authorities and community organisations.

In 2001 Park 23 was named Wirranendi, and in 2013 the spelling was revised to Wirrarninthi, (‘to become wirra’) which means to ‘become transformed into a green, forested area’. The name describes the process of ‘reclamation’ of the park being undertaken by the council. Activities include the construction of a Kaurna food and medicine trail and revegetation with native plants and protected indigenous flora.

Aboriginal associations

Prior to European settlement Kaurna people hunted and gathered food, medicinal plants and material for their shelters in the area now designated Wirrarninthi/Park 23. Following colonisation the area became increasingly alienated from the Kaurna. Trees and understory plants were cleared by the new arrivals. Timber was used for firewood and building materials, and European livestock grazed where indigenous flora and fauna had once flourished.

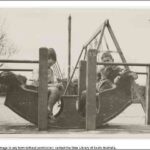

However, Aboriginal people continued to camp in secluded areas of the park, especially around the West Terrace Cemetery. They later took up residence in the West End and southwest corner of the city. When there was not enough space in local houses, some people used the West Parklands, including Wirrarninthi/Park 23, for overnight camping. From the 1930s to the 1950s the playground in the park was used by Aboriginal children living in the area in particular as a place to gather, play and, sometimes, sleep.

Many Aboriginal residents of Adelaide were later buried in the cemetery. At the commencement of the twentieth century it was associated with scandal when State Coroner Dr William Ramsay Smith was found to have robbed several graves of Aboriginal bodies, including that of noted Ngarrindjeri man Tommy Walker.

Aboriginal people continue to meet and camp in Wirrarninthi/Park 23. Their heritage and attachment to the area is increasingly recognised in initiatives such as the Wirrarninthi Interpretive Trail and the ‘Lie of the land’ artwork.

‘Lie of the land’ artwork

The ‘Lie of the land’ artwork, located on the western entrance to the city on the south side of Sir Donald Bradman Drive, is a significant feature of Wirrarninthi/Park 23. It was designed by Aleks Danko and Jude Walton and commissioned by the South Australian Government’s Art for Public Places in conjunction with the Adelaide City Council.

The work consists of 25 dome-like structures of Kanmantoo stone set in compacted granitised sand and surrounded by plantings of indigenous trees and kangaroo grass. It was inspired by a drawing in the Art Gallery of South Australia by Eugene von Guérard (1858), Winter encampment in Wurlies of division of the Tribes from Lake Bonney and Lake Victoria in the Parklands near Adelaide. It references traditional Kaurna dwellings (although they were constructed of plant material and were semi-circular rather than conical), some of the temporary shelters constructed by colonists in the West Parklands and Celtic brochs symbolic of the European newcomers.

The title, ‘Lie of the land’, refers to both the denial of Aboriginal occupancy and ownership of the land by European colonisers and the appearance of the landscape which led Light to found the city in this location.

The artwork was opened by Minister John Hill on 15 December 2004.

Kingston Gardens and bandstand

Little attention was paid to Wirrarninthi/Park 23 until the late nineteenth century. Post and rail fencing was installed and a scattering of trees was planted in the 1870s. During the 1880s tree planting was more extensive, but still haphazard. The southern section of the park continued to be used for rubbish disposal.

The fortunes of the park changed for the better after the appointment of City Gardener August Pelzer in 1899. He commenced a program of tree planting and replaced wooden fencing with cast iron fencing. However, his plan gave little benefit to local residents. The area was primarily used for the agistment of livestock into the early twentieth century. In 1907 between 200 and 600 sheep destined for the saleyards on North Terrace grazed in these parklands.

Residents and their representatives on the city council began pressing for park facilities accessible to the public in the first decade of the twentieth century. The council and Pelzer responded with the development of Kingston Park (later Kingston Gardens) on 3 acres (1.2ha) at the northeastern corner of Wirrarninthi/Park 23.

The gardens were named after George Strickland Kingston, who lived nearby in Grote Street. He had arrived in the colony in 1836 as its deputy surveyor-general. In 1838 Kingston established a business as an engineer, architect and surveyor. He was responsible for the design of several significant Adelaide buildings and the first monument to Colonel Light. Kingston was one of the founders of the South Australian Mining Association and an original shareholder in the Burra Burra copper mine. He entered the Legislative Council in 1851 as the member for the seat of Burra. Upon the granting of responsible government in 1857, he was elected to the House of Assembly and was the first to hold the position of speaker.

The area set aside for Kingston Park was fenced off and planted with trees, shrubs and flowers to Pelzer’s design. Seats were installed and electricity connected for the lighting of a bandstand. A long-awaited bandstand was designed by Alfred Wells and erected by W Essery. It was opened by Mayor Frank Johnson on 26 November 1909. The Advertiser reported the opening to be a success due to the crowd of 3000 West Adelaide residents attending: it concluded that this support showed the council’s expenditure to be ‘justified and appreciated’.

In the years immediately following its inception Kingston Gardens were improved by the addition of a bridge over a stormwater drain, flower beds, rose gardens, wattle trees and hedges. In 1912 it became a venue for Wattle Day celebrations managed by the Kindergarten Union of South Australia. However, the park received little attention following Pelzer’s retirement in 1932. The bandstand was used regularly for band concerts and events from the 1920s until the 1940s. From then it served largely as an ornamental structure in the park. In the late 1960s attention was again given to these parklands.

West Terrace Playground

In 1913–14 the establishment of playgrounds in the city was a focus of community debate. Pelzer and the Education Department welcomed the initiative. The department noted that the Sturt Street Primary School and the Observatory School in Currie Street used the West Parklands for recreational activities and said it could be a suitable location for a playground. However, in spite of the South Australian Town Planning and Housing Association indicating its willingness to drive a project in Wirrarninthi/Park 23, sufficient funds were not available. Wirrarninthi/Park 23 was also deemed unsuitable by the council. Other possible locations for playgrounds were not taken up during the First World War.

In 1918 proposals for playgrounds in the city were revived and the city council allocated 3 acres (1.2ha) within Wirrarninthi/Park 23 for this purpose. In August 1919 plans were drawn up by the Town Planning Association in conjunction with the council and an agreement was reached for the association to construct the playground. Initiatives in the building of playgrounds elsewhere delayed all but preliminary works on West Terrace. In 1921 the association invited the council to take control of construction and transferred funds to the council for the purchase of equipment.

A scaled-down West Terrace playground, surrounded by fencing to keep out grazing livestock, was completed during 1924. It was officially opened by Governor Sir Tom Bridges on 10 October 1924. The governor and other dignitaries, including the attorney-general and the lord mayor, were welcomed by a guard of honour of children from local schools. A pipe and drum band played, while the children sang the national anthem and performed a dance.

Controversy arose after the opening ceremony when disgruntled members of the public complained in letters to the lord mayor that no reference was made in the opening ceremony to the contribution of the Town Planning Association.

Pelzer’s original vision for the space has deteriorated over the decades. However, in 2007 the city council upgraded playground equipment and installed new fencing around the area.

Sport in the park

Wirrarninthi/Park 23 has a long association with sporting activities. The first sporting facility to be constructed was a tennis court in 1927. An oval was added to the west of Kingston Gardens and the playground after 1936. It was later named Bone Timber Reserve after the council’s Director of Parks and Gardens BJE Bone (1939–late 1960s). The southern end of the park provided courts for the South Australian Women’s Basketball Association (South Australian Netball Association [SANA] from c. 1970), one of the largest sporting associations in the state, from 1938.

Sporting activity in Wirrarninthi/Park 23 has not been without controversy. From the 1920s temperance and some Protestant church groups pressured the council to ban the playing of sport on the Sabbath. In 1939 the council acquiesced and passed a regulation effectively banning organised sport in all of the parklands on a Sunday. The ban continued until Dunstan Government removed it in 1967.

Further controversy arose following the construction of a new clubhouse for SANA in 1982 and the ongoing use of one of its rooms as an office. This use of the clubrooms had only been permitted on a temporary basis, and when SANA requested that the arrangement be made permanent in 1986, council refused. Supporters of SANA argued that it was being targeted as a not-for-profit women’s sporting organisation. Others defended the decision, maintaining that the integrity of the parklands was being compromised. They agreed with Lord Mayor Jim Jarvis who was concerned that the parklands were ‘being eaten away with facilities’. SANA was given a temporary reprieve.

In the early twenty-first century Bone Timber Reserve hosts both the Adelaide Cricket Club and the Adelaide Comets Soccer Club. The adjacent clubrooms are owned by the council but are licenced to the clubs. SANA transferred to a stadium and grounds at Mile End in 1998.

Late twentieth and early twenty-first century

In 1971 the southern portion of Wirrarninthi/Park 23 was named Edwards Park after a hero of the West End, Councillor Bert Edwards. Albert Augustine Edwards (1888–1963) was born in the West End of Adelaide and attended school there. He worked on market stalls and on racecourses before setting up a tea room in Compton Street. He later became the proprietor of several hotels. Edwards served as a Labor city councillor from 1914 to 1931 and was a member of the House of Assembly from 1917 to 1931. Throughout his life Edwards fearlessly supported Adelaide’s poorer citizens, inmates of institutions and groups that he saw as persecuted, under-paid or exploited. Although he was jailed for five years in 1931 for sodomy, Edwards remained popular in the West End. On his death in 1963, his considerable estate was divided among the poor. He is buried in the West Terrace Cemetery.

Wirrarninthi/Park 23 was re-invigorated in the 1980s and 1990s by extensive planting with indigenous species in the northwest section. Perennial wetlands and shallow stormwater retarding basins were also established. From the beginning of the twenty-first century these plantings have been enhanced with the development of an interpretive trail, accompanying sculptures and the ‘Lie of the land’ artwork.

Wirrarninthi/Park 23 continues to host sporting and recreational activities. Areas of the playground and gardens remain meeting places for Aboriginal people. The Adelaide City Council has begun implementing strategies to improve and to preserve indigenous plant species. Kaurna people are involved and aspects of their history are acknowledged in the park’s development.

Comments