The young Queen Victoria was crowned at a time when Britain might have chosen either revolution or electoral change. Fortunately reason prevailed and she began her reign in tandem with a more liberated though still immature parliamentary democracy, which was spurred on by the Reform Bill and which later spread throughout her empire. This was in many ways the dawn of true parliamentary democracy, and throughout Queen Victoria’s long lifetime the wheels of change moved towards ‘one vote, one value’.

Today there are 54 sovereign states in the Commonwealth of Nations whose subjects enjoy the benefits of those changes. The South Australian experience mirrors or in some respects even led the most liberating developments. From a time when the parliament was controlled by a male-dominated aristocracy of either Tory or Whigish allegiances, Queen Victoria lived to see the women of both New Zealand and South Australia gain the vote, and in 1895 South Australian women became the first ever to be able to run for parliament.

Ironically, it can be argued that of those who sat at the table to name the streets and squares of Adelaide in 1837, the majority were of liberal or even republican persuasion and for the most part were already sixty years before the time women could vote in support of the most liberal electoral measures.

On the day the Street Naming Committee sat to deliberate in May 1837, Alexandrina Victoria was merely the Princess Royal, but it was known that the next day she would reach her majority by turning 18. It was also known that King William IV was reaching his time and she would eventually succeed him. It would be less than a month later that the King died.

The Committee named the central square of the city of Adelaide after Victoria. It became the first named place of any kind, anywhere in the world, to venerate her. The princess preferred to be called Victoria rather than Alexandrina. Somebody present in the Street Naming Committee knew this and there was no dissent at the table about what was probably the first decision of the afternoon.

At a later date and after Victoria had married, the great lakes near the mouth of the Murray River were also named after the Queen and her royal consort. Lake Alexandrina and Lake Albert were symbolically linked to the Royal Household.

One of the most powerful connections between Queen Victoria and the city of Adelaide is just how many of those named in her streets were knighted by her during her reign. Lord Brougham, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Stanley and Lord Melbourne were already ‘peers of the realm’ at the time of her accession. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century William Hutt, John Pirie, James Hurtle Fisher, John George Shaw Lefevre, John Morphett, George Strickland Kingston, Richard Davies Hanson and Thomas Fowell Buxton were all knighted by her.

The Princess Alexandrina Victoria was born on 24 May 1819. She was the only child of Edward the Duke of Kent and Victoria Maria Louisa of Saxe-Coburg. She came to be in line for the throne as the niece of William IV and Queen Adelaide, who had been unable to deliver the King a surviving heir. The Duke of Kent was the fourth son of George III, and his wife Victoria Maria Louisa, the sister of King Leopold of Belgium.

While the Princess Royal preferred to be called Victoria, her godfather, Tsar Alexander II of Russia, insisted she be called Alexandrina. As her mother was also known as Victoria throughout her childhood, the young Princess became known affectionately as ‘Drina’. Her father, the Duke of Kent, unfortunately passed when she was only eight months old, causing her mother to jealously guard and overprotect her.

For most of her childhood the Princess’ uncle George IV was on the throne, and as he had younger brothers, including William IV, her position in the line of succession had never really been considered a realistic or even remote likelihood. After George IV died in 1830, and when William IV’s health began to decline in the spring of 1837, it became obvious that ‘Drina’ was headed for greatness.

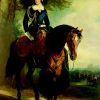

As Lytton Strachey declares, for all her years under her mother’s protective care and restraint, ‘female duty, female elegance, female enthusiasm, hemmed her completely in; and her spirit amid the enclosing folds was hardly reached by those two great influences, without which no growing life can truly prosper – humour and imagination’. Victoria was a serious child who did not read much, loved riding horses, and played a lot of shuttlecock and a variety of indoor pursuits like draughts and jigsaw puzzles. As a young woman she had an aura of calm and reassurance about her. Her demeanour was surprisingly stately for one so young..

As Victoria matured towards adulthood her inclination towards the Whig aristocracy and Whig politics evolved to the point where she became a trenchant supporter of their position. This might be explained in part by some of the books recommended to her during her teenage years by Lord Durham, a notoriously radical Whig. He persuaded Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent, to purchase Miss Martineau’s Illustrations of political economy, which goes a long way towards explaining why she found Lord Melbourne so instructive; he being a most erudite and relaxed member of the Whig aristocracy who suffered radicalism for the sake of power.

At the point of Victoria’s accession on 20 June 1837, those who honoured her name in Victoria Square in Adelaide were not to know just how close she was to become to ‘their Prime Minister’ Lord Melbourne. On the very morning her uncle died she received the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chamberlain in her chambers who announced that the King had passed and she was now Queen. With absolute calmness and a confidence belying her age, she immediately followed theannouncement with an hour-long private discussion with Lord Melbourne, who she asked to stay on as her Prime Minister. She assured him she would not trigger a general election which, as monarch, she was entitled to do, and that she intended to retain him and his Cabinet in government. It was also agreed he would take on the added and unusual responsibility for a prime minister of being her private secretary. Being so young and inexperienced in matters of state this was thought to be a sensible arrangement, and so it turned out to be. Their relationship took on an intimacy which both pleased and surprised. Some of the Tory persuasion were even offended, invoking rumours that because the Prime Minister was in such close contact with the teenage Queen, Victoria perhaps would be better addressed as ‘Mrs Melbourne’.

There was no evidence that Melbourne’s relationship with the young Queen Victoria was anything other than paternal, but the Tory press could not help themselves. Melbourne began ‘visiting … twice daily, where she saw him in her own private sitting room alone and where she received no other visitor. They communicated by letter and she wrote to him sometimes two and three times a day’.

They conducted the affairs of state in the mornings, engaged in outdoor pursuits and recreation in the afternoons, and dined together in the evenings. For the next two years the two were inseparable, which probably explains why the new Crown colonists of Victoria named their capital city after Melbourne. He was 58 and she, a slip of a girl, aged 18. Melbourne was very good for the young Queen because he tutored her on courtly manners and some of the social niceties, especially in the company of the Whig elites.

Victoria banished her mother from court and surrounded herself with more than a dozen ladies-in-waiting and attendants, most if not all of whom were drawn from the Whig aristocracy. Unfortunately, the bias shown by the Queen in this regard precipitated a constitutional crisis after the 1838 election. Melbourne and his Cabinet suddenly and unexpectedly found themselves with the thinnest of majorities and he decided he should step aside, allowing Robert Peel, the leader of the Tories, to form a government.

Victoria was unamused and could not abide Peel. Nevertheless, the change of government would have proceeded but for one thing: Victoria’s stubborn refusal to follow precedent in such circumstances which dictated that the Queen’s household staff be replaced by people nominated by the incoming and opposite Prime Minister. Peel withdrew meekly and called upon Wellington to intervene, in the hope that the most senior Tory statesman and national hero would be able to convince the young monarch. She also sent him packing!

In 1839, Queen Victoria was visited by her two cousins, the princes Ernest and Albert of Saxe-Coburg. Victoria became immediately transfixed by Albert and fell deeply in love with him. They were married in February 1840 and in the succeeding eighteen years Queen Victoria gave him nine children.

She presided over the greatest period of imperial expansion for Britain and her monarchy grew into one of the most enduring in British history. She outlived a long succession of British prime ministers which included Lord Melbourne.

She died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight on 22 January 1901. A veil came down on what was her own imperial century: Queen of England, Empress of India, Monarch to all British Commonwealth citizens.

Comments