Hindmarsh Square, located in the north-east of Adelaide, was one of the six squares designed by Colonel William Light in his 1837 plan of Adelaide. Originally designed as an oasis from the surrounding city, the Square would, however, see it’s size reduced and its lawns intersected by both Pulteney and Grenfell streets as transport and the city developed around it. Despite this, Hindmarsh Square continues to serve its intended purpose as an area of respite from its urban surrounding.

Pre-Contact History

Adelaide is located on the Kaurna people’s land of Tarndayangga, or place of the Red Kangaroo dreaming, with the location of Hindmarsh Square serving as an important meeting place for Elders before European colonisation. The colonisation and settlement of the Adelaide plains by Europeans, however, caused a dramatic disruption to the Indigenous population, causing people to move away and for the population to decline due to disease, violence and migration and segregation into settlements and missions.

European Colonisation and Establishment of the Square

Once the colonists had arrived in South Australia, Colonel William Light, the appointed Surveyor-General of South Australia, and his team set about choosing the location of Adelaide. After the location was chosen, Light designed a plan for the City which included a grid pattern with six squares and a surrounding parklands that would act as a ‘belt of greenery’ around Adelaide. This plan soon began to be imposed upon the landscape, with the designated areas for the squares fenced with wooden post and rail fences and left largely as they were, while the land around them began to be developed into a city.

Planting Schemes and Alterations

Hindmarsh Square, like the other city squares, saw numerous planting schemes and design alterations throughout its history, as the position of City Gardener changed hands and criticism over the condition of the Square increased. The first planting scheme was implemented by George Francis (later the first director of the Adelaide Botanical Garden) in 1854. Francis proposed a planting scheme after winning the tender put out by the City Corporation of Adelaide for the planting of the city squares. His plan involved planting a range of different species in the city squares, including acacia, almond, olive, gum, poplar and cypress trees, with 1500 trees to be planted in Hindmarsh Square alone.

However, with the appointment of William O’Brien to the position of City Gardener in 1865 a different planting scheme was implemented. He selected a series of ornamental trees, including Norfolk Island pines, Moreton Bay figs, white cedars, Kurrajongs and cassia trees. O’Brien also gravelled the paths and in the late 1870s erected ornamental iron palisade fencing to replace the Square’s decaying wooden post and rail fences. These fences were part of attempts by Lord Mayor William Bundy to beautify the city and improve the condition of the squares.

Hindmarsh Square was also unique among the squares due to it being the only square to contain a fountain before 1900. The fountain, donated by Councillor Adolf Heinrich Friederich Bartels in 1867, was positioned in the centre of the square where its north and south paths intersected. The fountain consisted of a figure of a boy holding a basin above his head. From this basin water spouted and flowed into a larger basin beneath the statue.

Despite these planting schemes and the installation of a fountain, the condition of the city squares steadily deteriorated in the late nineteenth century. Complaints about Hindmarsh Square were published in newspapers, such as the following published in The South Australian Register in 1867:

I frequently have occasion to pass through the square, and I never saw and smelt a more fever-generating mass of filth than is allowed to stagnate in that place…even the Sanitary Inspector, a man paid for the express purpose of remedying those evils, seems to have overlooked that one particular spot in his perambulations through the city. If anyone doubts the truth of what I write, let him go to the place and see and smell for himself, and if he is not convinced then I can only say he is sadly deficient in one or more of his senses.

Stagnant water wasn’t the only problem with Hindmarsh Square, as the writer continued on to complain about the state of the fountain:

may I ask why the fountain recently erected in Hindmarsh-square is not allowed to play. Surely it is not to be left long in that state without the water, to tantalize the thirsty wayfarer, for I consider there are too many of these useful things in and about the city to allow of one being left idle, especially one situated as this is in the most frequented part of town.

Complaints such as these continued into the late nineteenth century, resulting in the City Corporation establishing a special committee in 1897 to investigate the management and condition of the squares. Following site inspections, the committee recommended the removal of 24 trees and the appointment of a gardener for each city square.

As well as these measures, a significant contribution to the improved condition of the Square was the work of City Gardener August Wilhelm Pelzer, who was appointed to the position in 1899. He began by reseeding the lawns with couch grass, erecting hooped fencing around them to protect the lawns from people walking through them. Pelzer, not stopping there, also planned to decrease the number of trees in each of the squares. He removed large numbers of trees, specifically targeting pine, Moreton Bay fig and pepper trees, to allow more light and air through the Square. Throughout his time as City Gardener Pelzer continued to take measures to improve and maintain the appearance of the squares, such as the removal or replacement of trees, the redesigning and replanting of flower beds and the removal of fencing. He would remain City Gardener until his retirement in 1932.

Plantings and the removal of fences and trees were not the only alterations made, with tram tracks also laid throughout the squares. In 1909 the Municipal Tramways Trust (MTT) laid tram tracks and extended Pulteney and Grenfell Streets through Hindmarsh Square, dividing it into its present four quadrant layout. Following these works, Pelzer set about re-landscaping the Square, including replanting the lawns, erecting iron hoops around the flower beds and the planting of more trees and bushes. These landscaping works were completed by the end of 1910, a year after the tracks were laid. In conjunction with the laying of tracks, a small tramway signal cabin was erected in the northern section of Hindmarsh Square in 1912. Road widening works were also later carried out on Pirie Street in 1926, reducing the size of the Square and necessitating the removal of eight trees.

In 1935 Stanley Orchard was appointed by the City Corporation to the position of City Gardener, then renamed as the Curator of Parks and Gardens. Orchard immediately set about improving Hindmarsh Square following complaints about its condition from people who lived and worked around the Square. Works included the replacement of the old path system with diagonal paths, excluding the north-south and east-west pathways, the removal of 16 pine and all pepper trees within the Square and the implementation of a new tree planting program. In total the Corporation approved the removal of 86 trees, with 39 Golden Ash trees planted in their place. These were the main works that were undertaken by Orchard due to his sudden death on 15 March 1939, aged 58.

During the Second World War the city squares were appropriated by the government for training purposes and for the construction of air raid shelters. The requisition of the squares for defense purposes combined with the worsening condition of the trees, some of which were planted in the 1860s-70s, caused the condition of Adelaide’s squares to again deteriorate. The poor condition of the squares was brought to the City Corporation’s attention by Alderman John McLeay in 1944, however, it was not until 1953 that any action was taken. Under the direction of Council Gardner Benjamin Bone, the Parks and Gardens Committee undertook a tour of each of the squares in early 1953. For Hindmarsh Square, the Committee undertook the following actions: removal of one large pepper tree, five nettle trees and the replanting of sections of lawn that were in poor condition. The majority of the lawn and trees in the Square were deemed to be of a suitable condition and were retained.

Built Environment around the Square

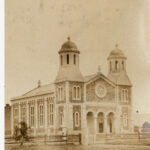

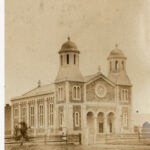

Hindmarsh Square Congregational Church

The Hindmarsh Square Congregational Church prominently featured in the built landscape surrounding Hindmarsh Square. The church, built on the corner of Grenfell Street and Hindmarsh Square, opened its doors in 1862 and with its twin bell towers became a dominant feature of Adelaide’s streetscape. For more than 60 years the church brought people into the Hindmarsh Square area through services, sunday schools, and by hosting fetes, fairs and meetings for organisations such as the South Australian Bush Mission. However, in 1926 the church was forced to close as the city became increasingly industrialised and families moved out into residential areas in the suburbs.

After its closure the church took on a new life as a radio station following its acquisition by the ABC in 1932. Despite the removal of its bell towers, the building retained much of its original structure and remained in use by the ABC until 1975. It was eventually demolished in the 1980s to make way for office buildings.

Aurora Hotel

Another prominent building facing Hindmarsh Square was the Aurora Hotel. Originally named the Black Eagle, the hotel was opened on the corner of Hindmarsh Square and Pirie Street in 1859. Soon after its opening the hotel became popular amongst the German community. This marked the beginning of an association between the hotel and the German community that would continue throughout the hotel’s history, despite name changes from the Black Eagle to the Marquis of Queensbury and then finally to the Aurora Hotel in 1894. In the twentieth century the Aurora Hotel became a more prominent landmark in the Hindmarsh Square area, growing to be three storeys in height with balconies and a balustraded parapet by 1938. By the late twentieth century, however, the pressures for development took their toll with the Hotel’s landowners demolishing the building in 1983 to make way for new office spaces.

The demolition of both the Congregational Church and the Aurora Hotel formed part of the Adelaide City Council’s redevelopment plan for the eastern side of Hindmarsh Square that saw tall commercial tower buildings replace what heritage buildings remained in the area.

Sir John Hindmarsh

Hindmarsh Square was named by the Street Naming Committee after Sir John Hindmarsh, the first Governor of South Australia. Hindmarsh came to be Governor as a result of his services and connections in the Royal Navy. After the first proposed Governor of the colony of South Australia, Colonel James Charles Napier, resigned in 1835, Hindmarsh went to London where he gained the influential support of members of the Admiralty. This support led to his selection as Governor of South Australia by Lord Glenelg, despite Napier’s recommendation that Colonel William Light replace him. Hindmarsh was favoured by the Admiralty due to his service in the Royal Navy, particularly his action aboard the H.M.S Bellerophon during the Battle of the Nile in 1798, where as a midshipman he became the only officer left on deck after the French ship, L’Orient, attacked. During the attack, the French vessel caught fire and became entangled with the Bellerophon, Hindmarsh, despite being wounded and losing sight in one eye, acted coolly to separate the vessels and save his ship from destruction. This action earned him the praise and thanks of Lord Horatio Nelson, a praise which Nelson repeated to Hindmarsh when he promoted him to Lieutenant in 1803.

This naval pedigree, however, did not win over the other colonists of South Australia, as he clashed with Colonel Light and other colonists over the location of the colony’s capital. Hindmarsh believed the capital should be a port, suggesting Port Lincoln. However, on arrival he deemed it unsuitable and agreed with Colonel Light, though argued that Adelaide should be closer to a port. This meddling earnt him the ire of Colonel Light and the Resident Commissioner, James Hurtle Fisher, who accused the Governor of undermining plans made by Light in order to turn the colony into his own creation. The location for the capital was put to a popular vote in 1837, with the result in favour of Light’s plan. After losing the vote, Hindmarsh faced further challenges to his authority and continued opposition from Fisher and his supporters. The Colonial Office in London eventually bowed to this pressure, recalling Hindmarsh from the colony and ending his governorship. Hindmarsh went on to become the Governor of the island of Heligoland and was later knighted in 1851. He lived out the rest of his days in England before dying in 1860.

Indigenous Associations

Indigenous people who remained in Adelaide after European colonisation tended to live in areas with affordable housing, such as the west end of Adelaide. In the early twentieth century, the Indigenous community in the City would increase due to changes in community attitudes and a policy of assimilation, which caused an increase in the number of Indigenous peoples migrating or returning to the City from missions, such as those at Point Pearce and Point McLeay. Adelaide attracted different groups searching for better opportunities of employment, education and housing. These groups included Kaurna people and the neighbouring Narungga and Ngarrindjeri peoples. Although unable to assimilate into the social life of the City’s pubs and clubs, Indigenous peoples created their own social life and places, with the city squares serving as community meeting places, where people could talk, disputes could be resolved and where rallies and protests could be formed. However due to its location away from areas where Indigenous people lived, Hindmarsh Square was not as popular amongst Indigenous peoples in Adelaide as Light or Victoria Squares.

More recently steps toward reconciliation have been made by the Adelaide City Council, with a reconciliation agreement signed in 1997. From this agreement the Kaurna Naming Project was formed. As part of the project Kaurna names were sought for each of the city squares. Originally Dr Rob Amery from the University of Adelaide, who specialises in the Kaurna language, suggested the name ‘Mullawirraburka’ for Hindmarsh Square. Mullawirraburka, also known as King John or Onkaparinga Jack, was a leader among the Kaurna people at the time of European Colonisation. Born in Willunga, Mullawirraburka was a skilful warrior and prominent figure among the Kaurna, evident in his ability to acquire four wives, more than any other Kaurna man at the time. The Adelaide City Council, however, decided to name the Square Mukata after one of Mullawirraburka’s wives (who was also known as Mogata or Mocatta).

Recent History

In 1978 a sculpture called Untitled was installed in the north-east corner of Hindmarsh Square. The pink granite sculpture was made by artist Paul Trappe. As well as this sculpture, Hindmarsh Square also currently features two fountains. One is located in the north-western section and features a water jet in the centre of the fountain with a white concrete basin decorated with four lions heads, while the other is a round red brick fountain with three water jets positioned in the north-eastern quadrant of the Square. Despite recent art installations and changes made to its landscape since the 1950s, Hindmarsh Square still retains elements of the picturesque and Gardenesque planting styles implemented by previous city gardeners William O’Brien and August Pelzer in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Comments