South Australia’s constitution is the body of laws and conventions which prescribes the powers and responsibilities of the various organs of government. The constitutional history of South Australia has been marked by both innovation and compromise, shaped by the original mode of colonisation, by the restraints of Imperial control and federal jurisdiction, and by popular democratic aspirations.

South Australia’s unique experiment in colonisation was first given legal form by the South Australia Act 1834, whereby the British parliament enacted a compromise between a wholly private colonisation project (seen as excessively republican in tendency) and the traditional colonial model of control. The Act vested political authority in a crown-appointed governor, while reserving responsibility for emigration and other functions to a semi-independent body of Colonization Commissioners. Subsequent additional constitutional instruments included the royal Letters Patent establishing the Province of South Australia and the Orders-in-Council establishing government (19 and 23 February 1836).

In reality

Unfortunately this hybrid scheme of governance proved unworkable in practice, as the financial burdens of colonisation exceeded the resources available to the commissioners, whose attempts to exercise a divided administrative authority provoked constant conflicts with Governor John Hindmarsh and his successors. In 1842 an ‘Act to Provide for the Better Government of South Australia’ saw the British parliament transfer the commissioners’ powers to the governor, who was henceforth to be assisted by a seven-member Legislative Council, both nominated and chaired by himself. After considerable criticism from the colonists and investigation by a British Privy Council committee (1849), an ‘Enabling Act’ in 1850 empowered the establishment of a 24-member Legislative Council, two-thirds of whom were elected. Despite the opposition of two successive governors (Henry Edward Fox Young and Richard Graves MacDonnell), an Act providing for responsible government by a two-chamber parliament passed the Legislative Council on 4 January 1856 and was forwarded to the Imperial parliament, where it was considered. Although royal assent was received in June 1856, the news did not finally reach Adelaide until 24 October, when the South Australian Constitution Act 1856 was formally proclaimed.

Obstructions

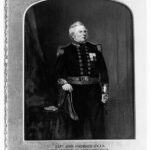

Meanwhile the idiosyncratic actions of the Supreme Court judge Benjamin Boothby saw South Australia playing a significant role in the development of all colonial constitutions, if more by rancour than design. After his appointment to the South Australian bench in 1853 from a successful practice at the bar in England, Boothby maintained that any South Australian Act which varied from English law was thereby invalid. In response to attempts to remove Boothby from office, the judge denied that South Australia’s parliament was legally constituted, and also asserted that fellow judges – who did not share his extreme views – had been invalidly appointed. Not until 1865 did the Imperial parliament pass the Colonial Laws Validity Act, which declared that only where British statutes were explicitly stated to apply to the colonies did they override colonial legislation. While Boothby’s final removal from office in July 1867 climaxed extraordinary efforts by the governor and parliament, the chaos for which he was responsible ironically provided a ‘charter of colonial legislative freedom’ (Castles & Harris, p134).

The 1850s saw another dispute, this time between the two chambers of parliament, over their respective powers in relation to money bills (that is, legislation concerning the raising and allocation of revenue). Similar disputes occurred in other colonial Australian legislatures, as lower houses whose members were elected by all adult males challenged the authority of less democratically constituted upper houses. Ultimately the question was settled by the ‘compact of 1857’, whereby the Legislative Council agreed that in future it would not seek to amend such bills.

Australian Federation

Towards the end of the nineteenth century South Australians made significant contributions to the debate on federation and to the drafting of the new federal constitution. By the time of the 1891 Sydney Convention Richard Baker had produced a Manual of Reference to Authorities for the Use of the National Australian Convention which was important in introducing a relatively unfamiliar form of governance to delegates. Many of the issues championed by South Australian delegates, especially at the 1891 Adelaide Convention, such as the protection of voting rights for women and the establishment of a federal system of industrial arbitration, found their way into the final version of the federal constitution.

Amendments aimed at improvements

Throughout the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, specific issues of government arose from time to time that required legislative amendments to the state’s constitution. The current Constitution Act, assented to on 18 October 1934, has been significantly amended by electoral reform measures. These arose from growing concerns that the electoral system, with its longstanding division into urban and rural zones, was excessively biassed in favour of country voters, and hence against the Australian Labor Party. Following the resignation of Sir Thomas Playford and the return of the Walsh Labor government in 1965, constitutional amendment was attempted but lost in the upper house. After Labor’s narrow defeat at the 1968 election, despite securing 54% of the two-party preferred vote, Don Dunstan as leader of the opposition made constitutional reform a central political issue. In response, Steele Hall’s Liberal and Country League government introduced electoral reform measures. The passage in 1969 of the Electoral Districts Act and the Constitution Act went some way towards ending the ‘Playmander’ that had kept Playford in power for more than 26 years, and helped secure the return of the second Dunstan government the following year. Dunstan’s reformist zeal saw the last vestiges of a property qualification for the Legislative Council franchise replaced by adult suffrage in 1973, and two years later the principle of ‘one vote, one value’ was enshrined in constitutional legislation.

The last two decades of the century witnessed some minor constitutional amendments dealing with ministerial appointments and casual parliamentary vacancies. In broader terms Australian federalism was undergoing substantial realignment. The Commonwealth of Australia’s use of its power to make revenue grants to less-advantaged states, and a narrowing of the states’ fiscal base, coupled with High Court decisions in the areas of external affairs, excise and interstate trade, have reshaped the relationship between the Commonwealth and the states, somewhat to the disadvantage of the latter. In 1986 the parliaments of the states, the Commonwealth and the United Kingdom moved in concert to enact the Australia Act. Among many other achievements, this statute confirms the constitutional position of the states within the Australian Federation. After the passage of this Act the parliament of the United Kingdom terminated its authority over the states and the Commonwealth, acknowledging that the states have full legislative capacity subject only to the Australian Constitution.

Comments