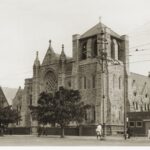

Built in a striking Gothic Revival style, St. Francis Xavier’s Cathedral is the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Adelaide. Named after the Patron Saint of Australia, it is the oldest Cathedral in Australia. First consecrated in 1858 (but not officially completed until 1996) and located in a prominent position on the corner of Wakefield Street and Victoria Square, the Cathedral has long been the heart of Adelaide’s Catholic community.

Early Catholicism in Adelaide

While St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral has been the central hub of Adelaidean Catholicism for more than 150 years, it was not the first Catholic Church in the city. Built in 1845 on the corner of West Terrace and Grote Street, St Patrick’s Church served as the house of worship for Adelaide’s Catholics. At this time, Catholics numbered around 15% of the population, almost exclusively comprised of poor Irish migrants. As very few of these migrants had significant wealth, the early Catholic Church struggled financially. Dr. Francis Murphy, Adelaide’s first Catholic bishop, raised funds slowly through personal donations from his small flock of mostly unskilled labourers. Unimpressed with the Church’s facilities in Adelaide, Murphy sought to construct a grand Cathedral. After a trip to England to gather financial support for this endeavour in 1846, Murphy returned with a design by prominent English architect Charles Hansom. However, these plans were found to be too extravagant and costly for such a small Catholic community.

Bishop Murphy was not deterred from his goal of a Cathedral for Adelaide, however, and in 1850 purchased a plot of land on Wakefield Street near Victoria Square. Even with the backing of English benefactor William Leigh, funding for this construction proved to be a constant issue. Murphy was only able to afford a plot of half an acre, at a time when purchasing full town acres was the norm. Furthermore, this half-acre located relatively distant from the central hub of the city around Hindley and Rundle Streets, and thus was comparatively cheap. The cost of 565 pounds could not be met upfront, and needed to be paid in regular instalments for 18 months.

As an alternative to the ambitious plans of Charles Hansom, Murphy held a public competition for the design of the Cathedral. This competition was won by local architect Richard Lambeth, whose design was feted by the Adelaide press. Construction of this new Cathedral began swiftly in 1851. Yet, when William Leigh was shown Lambeth’s design, he realised that it was a slightly altered plagiarism of Hansom’s original plans from 1846, scaled in a manner inconsistent with architectural norms. The potential for controversy over this revelation was muted by the fact that economic troubles had stalled construction in Adelaide. In 1851, gold was discovered in Victoria, and the allure of riches was irresistible to many Adelaide Catholics. This exodus meant that work on the Cathedral ceased, with only the foundations completed. The stress the gold rush placed on the Adelaide Catholic Church can be seen in the fact that Murphy tried to pawn his personal library to a Hindley Street bookseller to funding Church activities. However, those of Bishop Murphy’s flock who managed to strike gold started to sent some to him to sell for them, and their return to Adelaide brought an injection of fresh wealth to the congregation. As such, plans for the resumption of construction began by 1854.

Due to the controversy over the similarities between the designs of Hansom and Lambeth, Murphy approached Hansom to request a revised, more affordable design for Adelaide’s cathedral. In 1854, Hansom supplied the design that, at a basic structural level, the Cathedral maintains to this day. He was forced to accommodate the already extant foundations from Lambeth’s abortive design, but the increased wealth of the Adelaide Church meant that his new design was considered feasible. Hansom’s vision was a building in the Early English Gothic, a comparatively austere form of Gothic design. Construction began once more in 1856, and was nearing completion in early 1858. Unfortunately, Bishop Murphy died in April 1858, just months before its 11 July consecration. He was buried in the grounds of the nearly-completed Cathedral, the only individual buried within the city mile apart from William Light himself. This honour demonstrates how beloved he was in the early Adelaide community, by Catholic and non-Catholics alike.

Ongoing Construction

While St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral had been officially consecrated as a functional place of worship, it was by no means architecturally ‘complete’. The plans called for three distinct stages of construction, the first of which was finished in 1858. The frontage to Wakefield Street was still a temporary wall, hiding the façade of the Cathedral itself. By 1860, the side chapels, chancel and sacristy were completed.

In 1880, the fourth bishop and first archbishop of Adelaide, Christopher Reynolds, felt that the current Cathedral was not grand enough. Reynolds believed in a more strikingly Gothic vision for St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral, and sent to renowned English architect Peter Paul Pugin for a revised plan. As the full extent of Hansom’s plan had not yet been implemented, Pugin’s alternative was instead adopted upon receiving it in 1881. Yet, Reynolds’ ambition did not align with Church finances, and even though a foundation stone was laid in 1886, the expansion was shelved for being too costly. Electric lighting was installed in 1904. It was not until 1918, when Church debts were finally paid off in full, that serious consideration for this additional construction was undertaken. By 1922, however, Archbishop Robert William Spence concluded that these plans were still too expensive, and had them redrawn in a more conservative style.

The foundations of this new expansion were laid in 1923, at a grand gathering of Australian Catholics. All leading Catholic figures from around Australia attended, and a crowd of 8000 men marched from the West Terrace location of St Patrick’s Church to St Francis Xavier’s. Women were not permitted to take part. More than 10,000 pounds were raised by attendees for the completion of the Cathedral’s expansion, with the expectation that 10,000 more would soon be raised to ensure a debt-free construction. A local newspaper hailed the move to remove ‘blot and an eyesore’ of the unfinished Cathedral that had affronted Adelaide’s citizens ‘for more than two generations’, outlining that it was the duty of good Catholics to fund this noble project. A garden party for visiting Catholic dignitaries, attended by 5000 and including Adelaide’s political and financial elite, was held in Victoria Park after the consecration ceremony. Archbishop Mannix proclaimed this event the most impressive he had ever attended, and something that was only possible in Adelaide.

The new extension to the Cathedral was completed in 1926, and involved the construction of a bell tower. This tower was only intended to be temporary, and it did not match the style or ambition of Pugin’s plans.

Recent Operation

The Cathedral continued standard operations until 1985, when Archbishop James Gleeson declared that the belltower would be rebuilt according to Pugin’s original 1881 design. While support was offered from the National Trust, this plan stalled for almost a decade due to funding concerns. It was not until 1994 that work began in earnest. This involved reopening the limestone quarry that was used during the major 1923-26 expansion to ensure visual harmony. By 1996, this construction was complete, and the Cathedral itself was finally considered finished. As such, it was consecrated once again on 11 July 1996, exactly 138 years after its first stage was completed and 145 since its initial foundations were laid.

Comments