Sir Richard Davies Hanson was knighted by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1869 towards the end of a long and distinguished career in politics and law, both in Adelaide and New Zealand.

He is one of a small group of subjects who is honoured in more than one city, namely Hanson Street in Wellington, New Zealand, and until 1967, Hanson Street in Adelaide, which ran from Wakefield Street to South Terrace on the same line as Pulteney Street. Both were gazetted in his name.

To be considered for such an accolade in May of 1837, when he was barely into his 30s, is especially significant. Sir William Molesworth was the youngest to be memorialised on that day, but his status stemmed in some measure from the importance of his aristocratic family, even though he personally denounced the privilege which such families have access to. Hanson, on the other hand, who was also very young at the time, had no such advantage and was considered because of his loyalty, dedication and valuable contribution to the early deliberations of the South Australian Colonization Commission, to which he gave freely.

In 1831 Hanson drafted a proposal on behalf of the newly formed South Australian Land Company, incorporating a charter and some pertinent objectives based on the seventeenth-century templates of the American colonies.

By 1837 he was well known to the Street Naming Committee as one of the small group of very young radical dissenters who fell in behind Torrens and Gouger to give life and support to Wakefield’s innovative scheme of systematic colonisation in South Australia.

At the Exeter Hall meeting in London on 30 June 1834, when the concept was publicly launched, Hanson – then in his 20s – took a leading role. In a discursive explanation of this proposition he revealed an understanding of what might be necessary in the way of soil type, natural resources and topography for any successful colonial venture. This included a comprehensive appreciation of the little known coast and terrain of South Australia.

Richard Davies Hanson was born at home at 3 Botolphs Lane, London on 6 December 1805. He was the second son in a brood of nine children, including five boys and four girls.

The Hansons were essentially Congregationalists with a deep sense of disgust towards the excesses of privilege so reminiscent of the established church of the time. This contempt was revealed by Richard when he gave the inaugural address at the first meeting of the South Australian Literary and Scientific Association, formed in London in 1834. Richard’s mother instilled a strong sense of piety and virtue in her offspring, and under her firm tutelage the family held daily prayers and frequent but disciplined study of the scriptures.

Mrs Hanson had definite ideas about how her children should be educated. She sent Richard to a private tutor, the Reverend William Carver of Melbourne, in Cambridgeshire. He remained there until he was 16 years old. Hanson, somewhat reluctantly, was articled to the Reverend John Wilks (in 1822), a Methodist lawyer who practised in Boston, Lincolnshire. Still no more than a callow youth, Richard developed a calculating radical persona under the influence of Wilks, who spent twenty years as Secretary to the Protestant Society for the Protection of Religious Liberty before finally joining the Philosophical Radicals in the Reform Parliament. Hanson’s zeal, especially on this issue, was teased and shaped by Wilks, and more than thirty years later it still put fire in his belly.

Admitted to the Bar in 1828, Richard Davies Hanson practised law privately for a short time in London. This he did somewhat perfunctorily, for much of his time was spent in the gallery of the House of Commons, where the political and social questions of the day appealed more to his robust political disposition.

Between 1830 and 1835 Hanson became progressively more involved with the South Australian Association and the disciples of systematic colonisation. Hanson’s contribution was significant.

After the Exeter Hall meeting the Bill proposing a colony in South Australia passed easily through the House of Commons.Immediately after the Bill passed into law some of the intending colonists pressed for action. Whitmore, Torrens, John Walbanke Childers, Henry George Ward and others drew up a provisional list of likely commissioners, but it needed to be ratified before being put forward to the Colonial Secretary.

Once the Board of Commissioners was announced excitement spread like wildfire among South Australian Association supporters because it was then time for the board to appoint all the public officers. Gouger was appointed to the powerful position of Colonial Secretary in the colony, Captain John Hindmarsh sailed into the governorship under a fine breeze from Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, and James Hurtle Fisher became Resident Commissioner. Osmond Gilles, his pockets brimming with coin, essentially bribed his way into the position of Treasurer, and Brown and Hanson smoked a cigar or two together as they tried to weave some intrigue over the role of Chief Justice.

Unfortunately for Hanson, things didn’t pan out as he had expected. His application for Chief Justice did not materialise. It is likely that Hanson was seen to be too young and too outspoken. Torrens, in a somewhat conciliatory gesture, suggested that Hanson be appointed the Governor’s Private Secretary. Hanson was not impressed and declined, saying that he would settle for nothing less than Chief Justice, which unfortunately by this time had gone to Jeffcott. His patience wore thin and he walked away.

In1836 Wakefield engaged Hanson to conduct research and prepare and present evidence to the Committee, which he did more than capably. In 1837 Hanson briefly flirted with journalism, taking up an appointment with the Globe as a political writer. Then in 1838 he accompanied Lord Durham to Canada as Personal Secretary, as there had been some dissent in the British provinces led by Louis Joseph Papineau and others. Accompanying them were Charles Buller and E G Wakefield. Together they travelled the length and breadth of Canada, seeking evidence and gathering statistics in preparation for the famous Durham Report. Hanson had a strong hand in much of the written material in the report, as did Wakefield who, because of his jail sentence, was forced to be a ghostwriter. Afterwards, Hanson remained with Durham as Personal Secretary until the Peer’s death in 1840.

On return to England Hanson agreed to emigrate to the new colony as an agent, acting on behalf of the New Zealand Company, which Wakefield had now formed. Hanson’s role was to look for suitable tracts of land that he could then recommend to the company for purchase.

In New Zealand, it being a much smaller pond, Hanson was soon thrust into the limelight. The settlers at Port Nicholson elected him Vice President of their interim governing body. His impressive demeanour and incisive mind were immediately under notice. In 1841 he was appointed Crown Prosecutor in Wellington and successive appointments saw him as Crown Solicitor and Commissioner for the Court of Requests, Southern Districts. All of these posts he held with distinction. It was with some regret he eventually had to deliberate against the New Zealand Company on a matter of law. This naturally led to a falling out with Wakefield and so Hanson began to take more notice of what was happening across the Tasman in South Australia.

Hanson is arguably the most important legal figure who lived in South Australia during the mid- nineteenth century. From the time of his arrival in 1846 until his death in 1876 he progressed through a number of influential and powerful positions. In the following order he became Advocate General, constitutional lawyer, Member of Parliament, Attorney General, Premier, Chief Justice, Acting Governor and finally Chancellor of the state’s first university, University of Adelaide. This is an impressive list by anyone’s standards.

As the first politician in Adelaide to be given the appellation of ‘honourable’ he directly influenced the evolution of the political process, guiding the state from a dependency where power was vested in a British Governor and a Legislative Council of seven appointees to a bicameral system comprising both upper and lower Houses of Parliament, in which there were varying degrees of electoral representation.

By the 1850s Hanson had become an accomplished barrister in Adelaide. Governor Henry Young was especially impressed appointed him to the position of Advocate General within the Legislative Council of the day.

From the beginning Hanson spoke his mind and with sufficient eloquence to retain the Governor’s confidence, if not his agreement. In the time of his tenure, which lasted until 1856, his stature grew in the eyes of both the Council and the people. He framed and presented numerous Bills to the Legislature, among them the District Councils Bill which, when it was eventually passed, was to become the basis of an electoral map for South Australia.

The South Australian Constitution, which finally led to representative government through the medium of the State House of Assembly, was Hanson’s work, and when Boyle Travers Finniss became the first Premier in 1856, Hanson was the obvious choice for Attorney General.

Hanson’s was the fourth and thus far most lasting premiership, and he retained power from September 1857 until May 1860. He stood his ground trenchantly, carrying a raft of legislative change as he went. On matters of principle he stood for free trade and was implacably opposed to protection. He sought government revenue through duties and excises, declaring that direct taxation was counter-productive. Other Bills to pass during his premiership included Torrens’ Real Property Act,the first laws of patent; an Insolvency Act; and a Bill which partially consolidated criminal law in the state. However, the volatility of the electoral process would eventually claim him too. Hanson was finally defeated by a motion of ‘no confidence’ when he stood his ground on the issues of increased immigration and higher carrying capacity charges for squatters. Sentiment in the colony against continued immigration had been growing quickly because second-generation South Australians had begun suffering economic hardship and found it difficult to get a start.

As with all public figures there were many worthwhile and interesting events happening in Hanson’s personal life throughout his time in government. Not long after he came to Adelaide in 1846 he sent for some of his family in Britain. On 29 March 1850, at the age of 45 years, Richard Davies Hanson quietly married a 26-year-old widow from New Zealand by the name of Ann Scanlon. They lived firstly at Hanson’s Sturt Street residence and later in Jacob Hagen’s sixteen-room mansion on the corner of Pirie Street and East Terrace in Adelaide, which she and Richard rented. Theirs was a long and fruitful marriage bearing six children: two boys and four girls. Unfortunately, the youngest son predeceased Sir Richard later in life. In December 1850, Hanson suffered calamity when thrown from a horsedrawn gig, injuring his hip which led to some disability as time passed and accounted for his decided limp in late life.

In 1861, and with a briefcase full of life’s vicissitudes, Hanson finally became Chief Justice of South Australia. For more than a quarter of a century the job who some thought was rightfully his had eluded him. Now it was his.

In 1863 he moved from the city to Stirling, where he bought George Milner Stephen’s house known as Woodhouse. The family settled to a meaningful life at Mount Lofty.

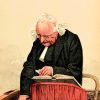

With Governor Ferguson’s departure from the state in 1872, Sir Richard Hanson was sworn in as Acting Governor, thus becoming the first Chief Justice to administer the province. He returned to private life when Governor Musgrave arrived in June 1873, preferring to spend more time in his handsome library. Moreover, his bad hip galled him so much now that he only ventured to the city to attend Stow Church or the occasional show at the Theatre Royal.

Hanson’s final public office in the state was as Chancellor of the newly established University of Adelaide. Always a strong supporter of education he was elected to the position from nineteen councillors. Throughout 1875, and mostly working from his library at Woodhouse, he framed the first University Statutes and prepared a financial plan for the institution.

On 4 March 1876, while preparing the inaugural speech which he was to deliver later that month and not feeling well at the time, he took a momentary break to walk in his arboreal garden where he collapsed with a heart attack and died.

A state funeral was held on 7 March 1876. The cortege was said to have stretched from the Supreme Court in Victoria Square where it started, all the way to West Terrace Cemetery.

It would be an injustice to characterise Sir Richard Davies Hanson as simply a dissenter, for although his personal development was grounded in non-conformity he did moderate his political position somewhat as he grew older.

Finally, it has to be said that for someone to whom the people of South Australia are so indebted, the decision by the Adelaide City Council in 1967 to remove Hanson Street from the plan of the city of Adelaide had in effect also removed an integral part of the history. Hanson Street and Brown Street were eliminated under a Local Government Ordinance. One can only assume that the proponents of this act were not properly briefed and that at some point in the future this decision will be reversed.

Comments