A prima facie case can be made for the inclusion of the name of John George Shaw Lefevre on the streets of Adelaide, merely because he was a South Australian commissioner. However, his contribution in the lead up to the South Australia Act made him one of the most powerful supporters of the plan to develop the colony.

By a strange juxtaposition between his personal and professional worlds Shaw Lefevre was uniquely placed to act as a mediator in the process and never wavered in his support for the scheme. Privately, he was a polymath, economic historian, member of the Statistical Society of London and Fellow of The Royal Society. In these circles he was personally known to the many utilitarians/radicals who were mounting a case for a colony. Professionally, he was employed in the Colonial Office, where he could subtly and cautiously influence policy. His role in the decision to plant a colony in South Australia became crucial; some would say pivotal. All together he spent twelve years of his life intimately involved with the project, in one way or another.

Through the 1820s, and after he graduated with such distinction from Cambridge, he began to move in elite intellectual circles in London and was known personally to George Grote, Colonel Robert Torrens, James Mill, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and all of the Political Economy Club, where he too was an inaugural member. Among the Whig elite he was equally at home.

When Lord Stanley, as the newly elected Colonial Secretary in the radical Reform Parliament (1832), personally invited Shaw Lefevre to become Under Secretary to the Colonies, Shaw Lefevre’s chance to influence the outcome in South Australia was assured.

Shaw Lefevre was extremely brilliant, but he was not the most assertive person. On the proposal for a colony in South Australia, he did, however, eventually offer advice. His subsequent request to be included on the South Australian Colonization Commission was acceded to, ensuring that his name was memorialised forever in a street facing Adelaide’s North Parklands.

Shaw Lefevre’s tenure as Under Secretary of State for War and the Colonies lasted from 3 April 1833 until 29 August 1834. When Lord Melbourne became Prime Minister, for some inexplicable reason Shaw Lefevre was removed. He had done such a good job organising financial reparation for all of Britain’s plantation owners in the wake of the abolition of slavery. However, his patron, the 3rd Earl of Spencer, Lord Althorp plucked Lefevre from the Colonial Office to take up an appointment as one of the three Poor Law commissioners; a thankless task, as it turned out, during which he could please neither his political masters nor the hypercritical press for the next seven years. They were the hardest years of his life. His health was tested almost to the limit.

John George Shaw Lefevre was born at Bedford Square in London on 24 January 1797. He was the second of four sons born to Charles Shaw (1758–1823) and Helena Lefevre, the daughter and heiress to John Lefevre of Heckfield Place in Hampshire. John was of French Huguenot stock through the distaff side of his family. The Lefevre name had come to be deeply respected in England, so Charles Shaw appended his wife’s maiden name to his own. Thenceforth, the family was known as the Shaw Lefevres. This family was also related by marriage to the Curries. In the 1780s their families shared a banking business known as Currie, Lefevre, James & Yallowley, which eventually evolved into Glynn, Mills & Co. and which is today the Royal Bank of Scotland. Both the John Shaw Lefevre and Raikes Currie families were close. They both lived for a time near Wimbledon Common, were practising Anglicans and well known to Pascoe St Leger Grenfell, another devout Anglican named in the Adelaide streets.

Shaw Lefevre and his older brother Charles had what can only be described as a privileged education. Both boys were sent in succession to Eton. Charles was enrolled in Winchester House and John in the less emotionally and physically demanding setting known as Dr Keate’s House. John George Shaw Lefevre was apparently not as robust as other boys. He was considered to be of a delicate constitution, somewhat protected by his mother, and in most accounts of his unexpectedly long life there are repeated references to his poor health. The irony is that despite his condition, he grew to be exceedingly ambitious and incessantly drove himself to a point where his health became a vexed issue.

After Eton, Shaw Lefevre went to Cambridge where he inherited his brother’s rooms at Mutton Court Corner, in Trinity College. He was an exceptional student whose dogged determination drove him onward to great acclaim, despite his sickly nature. He was the first Etonian ever to win the coveted Smith Prize of Senior Wrangler at Cambridge, his essays being described as extremely elegant and unusually superior to the rest of his competitors. He graduated in law in 1818 and was awarded a fellowship at Trinity in 1819, before taking his Master degree in 1821. A sojourn in France and Italy for the following twelve months wasn’t wasted. He became so proficient in French, Italian and Greek during this time that he was ever committed to a life of linguistic and mathematical exploration.

Later in retirement and as he approached 80 years of age, Sir John George Shaw Lefevre, as he was then known, had acquired no less than fourteen languages including Hebrew and Russian. He only began to read Russian after turning 65 and thereafter translated many a manuscript from a variety of languages into English.

One of the more exciting and moving things about Shaw Lefevre is that he attracted some of the sharpest minds of the day, hence his early membership of The Royal Society and the Political Economy Club. Lord Althorp, also a contemporary from the Political Economy Club, was so impressed that after Shaw Lefevre was called to the Bar in 1825, he offered to become his patron. Thereafter the young Shaw Lefevre conducted all the conveyancing for the Spencer dynasty, in addition to his own public service commitments.

This income was invaluable, especially when in 1824 he married Rachel Emily Wright, the daughter of the well-known Nottingham banker, Charles Ichabod Wright. Theirs was a true love match which sprang from a chance meeting in Buxton, Derbyshire, in 1822.

Shaw Lefevre went on to have two sons and six daughters to Emily, as she preferred to be called. His only surviving son, the Right Hon George John Shaw Lefevre, was much later created Baron Eversley, in 1906.

In 1831 Shaw Lefevre’s name was put forward to the Grey Government as someone who would be most suited to the exacting task of redrawing all of Britain’s electoral boundaries in preparation for the new Reform Parliament. He He met this task head on, and with the help of a brilliant surveyor by the name of Frederic Alonzo Carrington many of the two-member seats were abolished, as were the ‘rotten boroughs’, before marking out the new electorates instituted in more populous industrial cities.

Between 1833 and his retirement in 1875 Shaw Lefevre served on no less than sixteen government commissions. He is described as the quintessential public servant, with the air of a patrician. He was a mediator, advocate, facilitator, feasibility analyst and fastidious scribe. Many of his roles were unpaid, including his time as one of two Colonial Office representative commissioners to the South Australian Colonization Commission.

When Torrens was forced to resign from the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission in December 1840 because of a conflict of interest over land speculation in the colony, Shaw Lefevre took over as Land and Emigration Commissioner. He was also concurrently appointed as Joint Assistant Secretary and Commissioner to the Board of Trade (1841), a monumental responsibility given British hegemony on the seven seas. During his tenure there, it was Shaw Lefevre who designed the legislation for the registration of joint-stock companies.

For the next five years he drove himself incessantly and privately continued to take on more and more extracurricular activities. By 1845 it had become too much for him and he asked William Gladstone, the Minister for Trade in the Peel Government, to be relieved in some way. Gladstone obliged and invited Shaw Lefevre to become the Governor of Ceylon. In January 1847 John reluctantly turned it down on the pretext that he couldn’t ‘place’ his children, presumably for their education in Britain.

By the summer of 1847 he was invited by Lord Brougham, Thomas Babington Macaulay, Charles Babbage and other contemporaries from Trinity College to run for the parliamentary seat which was at that time dedicated to Cambridge University. This seat was considered a Tory stronghold and had not been contested by a liberal since 1832. Unfortunately, Shaw Lefevre came in at the bottom of the poll and retreated to the back rooms of the Board of Trade and the work of several other commissions.

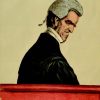

In 1846–47 he was given a chance to mediate in a dispute between the Royal Scottish Academy, the Edinburgh Royal Institute and the Board of Manufacturers over the nature and use of premises in Edinburgh for the placement of significant art treasures, meetings of The Royal Society and the training of promising artists. As a result, Britain now has a very fine Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, including a stunning portrait of John George Shaw Lefevre, painted in 1847 by Sir John Watson Gordon.

Shaw Lefevre went on to hold a succession of further commissions and in 1855 he succeeded Sir George Henry Rose as Clerk of the Parliaments – a position he retained until his retirement in March 1875.

In his private life John George Shaw Lefevre was a barrister, elected to the Inner Temple in 1850, dubbed Knight Commander of the Bath KCB by Queen Victoria in 1857 and a director of the South Western Railway.

He became one of the founders of the Atheneum Club, an early member of the London Library and a member of the Reform Club. With such a capacious intellect it was inevitable that he would also have links to the universities and other scientifically related organisations.

Besides the obvious association with Lord Brougham and the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge he would often gather with like-minded scientific and mathematical intellectuals in what would be described today as a ‘think tank’. Hill’s printing machine and Wheatstone’s electric telegraph were two ideas which sprang from this collaboration.

However, perhaps his most important community service was given to the new London University, established in the late 1820s especially for the sons and later daughters of Protestant dissenters who couldn’t meet the Religious Test at entry to either Cambridge or Oxford. In 1842 Shaw Lefevre became the first Vice Chancellor of the prestigious university and was popularly elected every year thereafter until 1862. His genius for mathematical theory and application eminently qualified him for the position. A year after he was knighted he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Civil Law at Oxford (1858) for his exceptional talents at law and as a linguist and classical scholar.

In 1862 there was a noticeable decline in his health and he resigned both as a civil servant and as Vice Chancellor of London University. His contemporary and equally gifted classical scholar George Grote succeeded him in the position. However, Shaw Lefevre’s knowledge and expertise were still sought and in his declining years he became involved from the sidelines. In 1866 he was appointed a commissioner on the Digest of Law. He also prepared an analysis of the Standing Orders of the House of Lords. He retired from all responsibilities on 6 March 1875.

John George Shaw Lefevre led an outstanding life. His career straddled ‘the law, the hustings, the bureaucracy, the academy and the library in a fascinating but not wholly successful search for self fulfilment’. This man of such mild temperament and measured judgement died suddenly but peacefully at Margate on the Kent coast in August 1879. Sir John George Shaw Lefevre KCB, FRS, DCL (Oxford) was in his 83rd year.

Comments