Penola-born polar explorer who won the British Polar Medal with silver bars for both the Arctic and Antarctic. After assuming leadership on an Arctic expedition, Rymill led the highly successful British Graham Land Expedition (1934-37) to the Antarctic which established the existence of the Antarctic Peninsula and ‘changed the face of Antarctica’. Rymill returned to farming at Penola and was heavily involved in the local community, especially equestrian events.

Youth

John Riddoch Rymill was born on 13 March 1905 at Penola Station, South Australia. He was the younger son of Mary (née Riddoch) and Robert Rymill. Rymill was educated in Adelaide and then at Melbourne Grammar but evidence of dyslexia (not then recognised as it is today) made academic life challenging until he realised the practical use for maths in surveying and the reading of polar literature. Rymill excelled in practical pursuits, thrived on life in the bush, developed a retentive and reliable memory and by the age of 18 was determined to become a polar explorer.

In 1923 Rymill set about designing his own course of tertiary education for the makings of a polar explorer in England. He learnt to survey and navigate at the Royal Geographical Society in London, to ski and mountaineer in Switzerland and to sail in Essex. In 1927 Rymill won the first National Skiing Championship in Australia (Kosciusko). He studied nutrition and cooking in Cambridge, book-keeping and anthropology in London and learnt to fly at Hendon (Middlesex) where he went solo after only 70 minutes of instruction. Rymill obtained his international aviator’s certificate in 1928.

International Expeditions (1928-29)

Rymill commenced his international and anthropological expeditions in 1928 with a big-game hunting trip to the Canadian Rockies where he started to adopt the native methods for comfortable camping in all weather conditions. Then in 1929 he joined Donald A Cadzow (expedition leader) on the Franklin Motor Expedition on behalf of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology to the Canadian Prairies to collect artefacts of the First Nation people whose elders were concerned their old rites, traditions and sacred objects would be permanently lost.

Polar/Arctic Expeditions (BAARE; 1930-31)

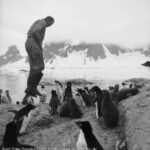

In 1930 Rymill was invited by Gino Watkins to join his 1930-31 British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE) to Greenland. He took every opportunity to learn from the Eskimos (as they were then known), to hunt on the treacherous sea ice, to learn their techniques of travelling and hunting, and to live comfortably in the cold. Rymill’s bespoke seal-skin hunting kayak is now on display in the Australian Polar Collections gallery at the South Australian Museum.

During this expedition Rymill impressed his colleagues with his aptitude as a (6‘ 4” tall) pack-horse, as he would regularly carry loads of 160 pounds (72kg) up the steepest terrains. One task Rymill was given was to survey and establish the ‘Ice Cap Station’ which comprised three domed tents. Approximately four months later he was given the task of finding that station, of which only about 10cm of the ventilator (atop the main tent) was still visible in the featureless landscape. This he did, thereby retrieving an extremely grateful August Courtauld who had been interred for 150 days in solitary confinement eating raw oatmeal in the dark.

Rymill loved dogs and became a skilful sledge driver (with his Australian kangaroo hide bullock stockwhip).

Pan-Am East Greenland Expedition (1932-33)

The following year, 1932, Rymill again joined Watkins as second-in-command. It was during this expedition that Watkins went out sealing alone and never returned. His kayak was found, along with his discarded wet clothes some distance away on an ice-flow but it was never known how he died. Rymill carved and erected a cross in his memory. As second-in-command, he assumed leadership of the expedition and continued with its surveying work. Rymill returned to England in late 1933.

Antarctica – British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE, 1934-37)

Rymill’s ultimate goal was to explore the east coast of Graham Land (thought to be an archipelago), the last major geographical feature on the earth’s surface still to defy human discovery. He boldly and correctly surmised that sailing along the west coast, where the katabatic winds would blow heavy pack-ice away from the coast, would thereby provide a narrow passage of open water for a small ship to navigate, and enable access to the continent. From the western side, they proposed to sledge across the channels Wilkins reported in his 1928 flights to then explore the east coast.

But first, he had to raise the money for this three year odyssey, and fulfil his dream of going boldly where no man had ever gone before. He went on to say: ‘although we would not know it at the time, the BGLE was the last big private expedition to the Antarctic, and I wondered whether I would ever raise enough money – especially during those Depression years of the early thirties’.

Rymill soon had a team of 15 ‘strong, sound men with the spirit of youth in them’ with an average age of 25. These men included some serving military officers, young Cambridge graduates and some specialists in their fields. Incidentally, Rymill asked all members to provide their own three-year supply of toilet paper, as a way of ensuring they fully realised their commitment!

Rymill purchased an old Brittany three-mastered schooner (103 feet [31.4m] on the water-line; gross tonnage of 130 tonnes) and re-named it Penola (after his hometown). So within less than a year of arriving back in England, Rymill and the Penola set sail from St Katherine Dock (London) on the 10 September 1934.

In February 1935 the Northern Base was erected on Winter Island (Argentine Islands) at the site where Wordie House now stands. Sledging journeys and scientific studies commenced but only on a local basis. Initial sledging exploration plans were hampered by factors such as significant repairs to the Penola, unfavourable sledging conditions and the absence of Crane Channel as reported by Wilkins, but rather a continuous range of mountains towering to 1,700m (5,600 feet). Rymill was becoming adept at changing plans as situations presented and due to a variety of challenges used the time at the Northern Base for valuable husky breeding and training; useful and pioneering scientific work and surveying.

A year later in February 1936 the Expedition moved its base to Barry Island (in the Debenham Islands in Marguerite Bay) and established the Southern Base where they would live for the next year. Significant sledging journeys, surveying and other scientific work was undertaken in the year following. After one such trip Rymill wrote in his diary ‘as we sledged along I was impressed by the thought that here was all this strange grandeur round us, and we – people of the twentieth century… were the first to see it since the world began’.

Some nervous times were encountered such as when the ice on which the men, their sledges and dogs were camping started to crack due to the force of the winds and were being blown out to sea. After a challenging sledge across the broken sea-ice they reached an island which they aptly named ‘Terra Firma’. One man shouted with satisfaction ‘Well, this can’t blow away’ to which came the reply ‘No, but it may be a volcano!’

In entirety, the BGLE had explored and surveyed nearly 2000km of previously unexplored coast and conducted numerous scientific studies. They established that Graham Land was a continuation of the Antarctic Peninsula and not an archipelago as previously believed and discovered King George VI Sound.

When Rymill was awarded the American Geographical Society’s Livingstone Centenary Gold Medal, the citation stated: ‘The survey work of this expedition constitutes probably the largest contribution of accurate, detailed surveys on the Antarctic continent made by any expedition’.

All members of the BGLE received the British Polar Medal – Antarctic Bar. Rymill was the first (along with his four Greenland colleagues) to be awarded the British Polar Medal with both the Arctic and Antarctic bars. He was also awarded the Founder’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

The BGLE successfully bridged the heroic and modern ages of Antarctic expeditions. Rymill and his men were credited with ‘changing the face of Antarctica’ and ‘setting new standards’. The BGLE comprised a multi-disciplinary, skilled and competent team, with experienced dog-sledging drivers and camping techniques, nutritional knowledge, meticulous and flexible planning, use of aircraft (de Havilland Fox Moth), limited radio communication, tractor, motor launch, polar field work and navigation. The BGLE was a most harmonious team and a happy expedition which returned home in amity. It revolutionised Antarctic exploration and paved the way for more professional expeditions.

As the BGLE sailed away from their Southern Base, headed for England and coinciding with Rymill’s thirty-second birthday, Rymill wrote in his diary ‘I was genuinely sorry to be leaving a land which will always hold for me the memory of a grand country, shared with grand companions.’

One of Rymill’s proudest achievements was that the BGLE was the first major polar expedition to suffer no loss of life due to accident or subsequent suicide.

He published the official account of the BGLE in his book Southern Lights (first published in 1938).

Family – Penola

Rymill married Eleanor Francis on the 16 September 1938 in London and they arrived back in Penola on 1 January 1939 to resume life on Old Penola Estate.

Rymill enlisted in the Royal Australian Navy on the 2 December 1941. His navigational skills resulted in his being posted to the Operations Division of Naval Headquarters in the Victoria Barracks on St Kilda Rd, Melbourne. He was discharged on 22 July 1943 (with the rank of lieutenant) to resume primary production.

Rymill had three children – a son Peter, daughter Mary (who lived for one day) and a son, Andrew. On the farm, perennial pastures of phalaris, rye grass and strawberry clover were sown with superphosphate and mineral trace elements, and then animals were bred to fully utilise the new, enhanced levels of nutrition. This involved establishing studs of Angus cattle and Corriedale sheep, both of which provided the genetic material to subsequently lift the productivity of the commercial herd and flock.

Rymill commenced numerous community activities. He had been made a Justice of the Peace (prior to the war) and was elected to the Penola District Council. Rymill was heavily involved in establishing the Penola War Memorial Hospital and was President of the Penola Show Society to which he incorporated show jumping in the 1950s.

Rymill and his wife Eleanor donated funds to establish the Rymill Memorial Hall at the Penola Show grounds which was unveiled by Eleanor on the 10 October 1953. After initiating a series of one day events on Old Penola Estate, he co-founded the Penola Pony Club in 1958 and was the first president of the State organisation. He also served on the Federal council of the Equestrian Federation of Australia. Rymill rode competitively himself and, aged over 50, was very proud to complete the course of the Mount Gambier One Day Event successfully.

Rymill died in September 1968 in Adelaide as the result of a motor accident near Tailem Bend, South Australia aged 63.

Awards

- 1927, Winner – Australian National Skiing Championship (Mt Kosciusko)

- 1.11.1932, Polar Medal, in silver, with clasp inscribed “Arctic, 1930-1931” (British Arctic Air Route Expedition, 1930-1931)

- 1934, Royal Geographical Society Murchison Award

- 20.6.1938, Royal Geographical Society Founder’s Medal [No medal of recent years has been better earned. There was a large territory of the Antarctic…which had never been explored by a land party … a fine story of triumph over initial difficulties and eventual great success. (Royal Geographical Society AGM Minutes, 20th June 1938)]

- 14.9.1939, David Livingstone Centenary Gold Medal of the American Geographical Society [The work of the expedition constitutes probably the largest and most accurate surveys of the Antarctic continent ever made.](Official medal citation as reported in Advertiser, 15th September 1939)]

- 20.10.1939, Silver Polar Medal awarded for the Antarctic (ANTARCTIC 1935-37 British Graham Land Expedition – JR Rymill [& 15 others] London Gazette, 20th October 1939)

Commemorated by

- Rymill Hall (Penola)

- Rymill Bay (68o24’00” S; 67o 03’00”W; Antarctic Peninsula)

- Cape Rymill (69o29’02” S; 62o 27’26”W; Antarctic Peninsula)

- Rymill Coast (71o00’00” S; 67o 30’00”W; Antarctic Peninsula)

- Mount Rymill (Prince Charles Mountains, Antarctica)

- Footpath Plaque (Penola)

- Commemorative horse trough at the Penola Pony Club

Comments