Pulteney Street is the counterpoint of Morphett Street on Colonel William Light’s plan of the city of Adelaide. It runs north/south and parallel to King William Street, embracing Hindmarsh Square. It is perhaps the only street successfully nominated by Governor John Hindmarsh on the day the Street Naming Committee met to decide the street names of Adelaide.

Since, as the vice-regal representative in the colony Governor Hindmarsh presumed it was his prerogative to name any places, features, streets or points of interest, he made quite a show on board the HMS Buffalo en route to Australia. On several occasions he made it clear that he was going to venerate some naval heroes when the plan of the city had been decided.

James Hurtle Fisher, the Resident Commissioner, had other ideas, believing all the power for such decisions lay with him as the principal representative of the South Australian Colonization Commission in the colony. To defuse the potential conflict, which looked like escalating into an early confrontation in the new settlement, Fisher tricked Hindmarsh into accepting that a committee of twelve should be formed to undertake the process. Hindmarsh didn’t foresee the outcome or the political colour of the chosen committee and was at a disadvantage throughout the afternoon on which all the street names were decided.

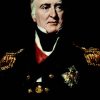

Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm was the only one of his heroes to be accorded an honour and there were at least three reasons why the committee might have agreed to this decision, while rejecting so many others. It is almost certain that Pulteney Malcolm was nominated by Hindmarsh, or at the very least by Judge John Jeffcott on his behalf. Firstly, Hindmarsh owed the accolade to the Admiral because it was he who gave testimony to Colonial Secretary Lord Glenelg as to his capacity and suitability for the appointment of Governor. This was reason enough! Hindmarsh had a long association with Pulteney Malcolm and had served under him in the Royal Navy throughout a long and distinguished naval career. Secondly, it is likely that Pulteney Malcolm had other supporters on the Committee because he made good on his promise to procure the Buffalo from the navy as a vice-regal ship for the commissioners and colony. Thirdly, Gouger might very well have been personally and favourably disposed towards him because Pulteney Malcolm had given him and his family a favourite Scottish lowland shepherd dog for their use in the colony.

There were at least three streets and one square named on that day on 23 May 1837 in which a name, other than the surname of the person venerated, took precedence. These were Barton Terrace (John Barton Hack), Carrington Street (John Abel Smith), Hurtle Square (James Hurtle Fisher) and Pulteney Street (Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm).

Trying to find explanations for this has proved elusive; however, in the case of the Pulteney attribution, there are a few reasons which seem plausible. There were several Malcolm brothers. Pulteney was the third son of seven Malcolm boys, almost all of whom distinguished themselves in some way. James, John and Pulteney Malcolm were all Knight Commanders of Bath. They were known collectively as the Knights of Eskdale. It would seem logical therefore to call the street Pulteney Street to distinguish the Admiral from his equally famous brothers. The most likely explanation, however, is that the name Pulteney was considered more dignified in the sense that it had much more status in Britain, being derived from the aristocracy and the Earls of Bath. More specifically, it was the acquired name of his father George Malcolm’s closest friend, to whom he owed so much.

The Malcolm boys had come from humble Scottish origins. They were commoners. Their grandfather Robert Malcolm, whose family had long before come from ancient lineage in Cupar, Fifeshire, was a respected minister of the cloth in the Parish of Ewes. The family migrated to the lowland border country in the County of Dumfries in the early-eighteenth century. Here, Robert Malcolm, the patriarch, had by careful and shrewd management set up the family on small sheep farms where they gained a growing reputation as managers of agricultural and pastoral lands. George Malcolm followed his father into pastoral improvement and sheep breeding and is said to have raised seventeen children at ‘Burnfoot’ on the banks of the River Esk.

In his formative years, George became very close to William Johnstone, another lowlander in the district. As friends these young men were inseparable and were neighbours in Eskdale, Dumfriesshire. Both married at about the same time, in the 1760s; George to Margaret Pasley, the sister of Admiral Thomas Pasley; and William to Frances Pulteney, whom he had met in London and who was an heir to the estates of the Earls of Bath. After William Johnstone’s marriage to Frances, and on the occasion in which she inherited the Bath estates, her new husband took her family name and the Pulteney armorial crest out of respect for the line.

Thereafter he was known as William Pulteney and not William Johnstone. This was not uncommon when someone married above themself. From that day onward the Malcolm family received great patronage from Frances and William Pulteney. George Malcolm took over the management of the vast Pulteney estates in Scotland and gave good prudential advice to his patron as well. By 1768, the year of the birth of Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, the financial future of the Malcolms was very promising, hence the name of Pulteney for George’s third son as a tribute to his dear friend.

Our subject Pulteney Malcolm may have been raised on a farm in Scotland, but on 20 October 1778, at the tender and malleable age of 10, he entered the Royal Navy as a Midshipman on the Sybil under the command of his maternal uncle, Thomas Pasley, then a naval Captain. He was to spend the rest of his life at sea and virtually none of it on land. It is difficult to imagine the shock and awe that a 10-year-old boy might experience aboard a sailing ship en route to the Cape of Good Hope, especially among hardened seafaring men. This was not uncommon; however, in an exquisite brace of coincidental events replete with serendipity, and which highlight the confluence of naval activity, colonisation and exploration during this time, two unique Australian-related anecdotes have been uncovered.

Firstly, the voyage to the Cape saw Captain Pasley recover the documentation, several survivors and some of the funereal remains of Captain James Cook. Cook had met his end after an illustrious career as a naval explorer in the surf and sand of Hawaii. Secondly, and just ten years later in July 1790, a decade or so after Captain Cook had claimed Australia for Britain, three of those with street names on the Adelaide plan were aboard the one ship at the same time: Governor Hindmarsh, Matthew Flinders and Pulteney Malcolm. Hindmarsh was only 5 years old. The ship was a new 74-gun ‘Man O War’ – the HMS Bellerophon. She was laid up at Chatham, more or less on a permanent basis, until needed for naval warfare. Hindmarsh’s father was a gunner on the vessel and he and his young son spent most of their time living on board.

Commander Pasley was in charge of the Bellerophon and eventually took her into combat. The two sailors along with John Hindmarsh on the payroll at the time were 16-year-old Midshipman Matthew Flinders and Pulteney Malcolm, a 22-year-old Lieutenant serving under his uncle’s command. All three were crew at the same time at what was the beginning of a long association between these naval men. Commander Pulteney had a magnificent naval career and served in almost every part of the world.

Remarkably, the pinnacle of Pulteney Malcolm’s career and greatest notoriety came with Napoleon’s exile. The victors against Napoleon agreed to maintain a blockade on the island of Saint Helena in the mid Atlantic. Pulteney Malcolm was given charge of the naval squadron and the station there, and it was his responsibility to see that the Emperor remained personally safe but securely removed from any influence in France or elsewhere. He was the only British naval officer who Napoleon came to respect. With such a background it was not at all surprising that Captain Hindmarsh later sought Pulteney’s support in his application for the governorship of South Australia.

Sir Pulteney Malcolm was born on 20 February 1768 at Douglan, near Langholm, the third son of George and Margaret. After his voyage on the Sybil under the tutelage of his uncle, Captain Pasley, his career at sea reads like a succession of small steps towards eventual notoriety and ultimate naval glory.

Pulteney Malcolm assumed command of the Saint Helena Station and was personally responsible for both the welfare and restraint of the Emperor between the spring of 1816 and winter of 1817. In 1821 he was promoted to Vice Admiral and ultimately became Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean from 1828 until 1831. In command off the coast of the Netherlands in 1832, the fleets of both France and Spain were under his orders. At the time of the passage of the South Australia Act in 1834 he was again Commander in Chief in the Mediterranean and retired later that year.

The most revealing portrait of Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm comes from his most important imperial enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte. He at least looked into the face of Pulteney Malcolm and told us what he saw – an open, forthright man who carried himself well and who could be trusted to speak his mind. As far as the evidence will allow, Pulteney Malcolm was highly regarded as a person. Very few people maligned him.

At the mature age of 41, after being at sea for most of his years, Pulteney Malcolm married Clementina Fullerton Elphinstone, then 34, at Marylebone in London on 18 January 1809. She was born in 1775. They were both unusually advanced in age at the time of their marriage and because of his commitment to the navy, Pulteney departed just weeks afterwards and returned to sea. Clementina, or Tina as she was known to family and friends, was the eldest daughter of William Fullerton Elphinstone, the third son of the 10th Lord Elphinstone and a director of the East India Company. She was also a niece of Admiral Lord Keith. Hers was a strong ‘Scottish Tory family who produced a succession of admirals, generals, and governors general to serve Georgian and Victorian England’.

Despite the little time they had together during their marriage, Pulteney was at least home frequently enough for Tina to bear him two sons. George Malcolm was born in 1812 and on Saturday 27 December, 1817 William Malcolm was born in Upper Harley Street, where the Malcolms had a London home. There is evidence also that although Pulteney Malcolm spent much time at sea he was a loving and dutiful husband who used to write long and informative letters to his wife on frequent occasions. That is why it must have been a blessing for him to be given charge of the blockade on Saint Helena. At least there he had a solid eighteen months with Tina, even if it was in isolated circumstances. Both he and Tina endeared themselves to Napoleon in a way which is worthy of comment. None of the other naval officers were greeted with such accord. In fact, most were treated with angry outbursts and a degree of contempt. In the abundance of quiet time on the island both Pulteney and Tina spent a lot of time in conversation with the Emperor. Tina even managed to beat him at chess. He was bemused and enchanted by her quickness.

Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm had two houses in and near London; the one in Harley Street and another at East Lodge in Enfield, where he ultimately died. His time in England was punctuated with trips back to Scotland.

On 23 March 1830 Pulteney Malcolm was as usual away at sea on duty. On that day he laid the foundation stone to an expanded facility in Malta, where the Admiralty had taken over the Villa Bighi for use as a naval hospital. So many sailors from the Russian and British fleets were injured during the Battle of Navarino in 1827 that such an initiative was considered essential. It remains today as an outstanding example of late-eighteenth century Italianate architecture.

Ironically and rather cruelly at this time, when Pulteney was Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, cruising between Gibraltar and the Dardanelles, his wife Tina was languishing at home with a tumour developing in her breast. She was alone. Both of her boys were at boarding school and Pulteney was at sea. True to her stoic and determined character she concealed the problem for a time and kept a detailed account of the progression of the disease and all the treatments she had to endure. Pulteney continued to write to her and shower her with gifts of fruit and sculptures from afar without having any idea of the severity of her illness. She had two operations and although the Egyptians performed similar operations thousands of years earlier, Tina Malcolm was probably among the first women to formally undergo a mastectomy in Britain. Unfortunately, it was not a success and on 19 November 1830 she passed away.

Pulteney Malcolm’s losses were not to end there. Just a few years later and through the period when he was being showered with honours, one of his sons also died, of the plague, in Constantinople (Istanbul). The pressure on the ageing Admiral thereafter finally took its toll and he too died at East Lodge, Enfield on 20 July 1838, aged 70.

At the time of his death he had attained the highest honours possible for a naval man and was known as Sir Pulteney Malcolm, Admiral of the Blue GCB and GCMG. He was made GCMG on 21 January 1829, GCB on 26 April 1833 and promoted to full Admiral on 10 January 1837. Statues were erected to him in Langholm, Scotland and in St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

He is remembered by Pulteney Street in Adelaide, Point Malcolm on the southern west coast of Australia, near Esperance, which was named by Matthew Flinders, and Malcolm Island at Sointula, off the coast of Vancouver in Canada. He held land in South Australia in absentia as did others of the Malcolm clan, on Lake Alexandrina at the property known as Poltalloch Station, near Narrung.

Comments