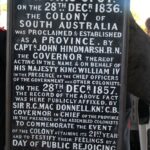

The first reading of the vice-regal proclamation at Holdfast Bay on 28 December 1836 is one of the best known events in South Australia’s history. It has been commemorated by a ceremony each year in Glenelg since 1857. Yet the intent of this proclamation is often misunderstood. It did not ‘proclaim’ the province of South Australia as such. That happened in Britain before the settlers left, with the passage of the South Australia Act in 1834, and the issuing of the Letters Patent of the province in February 1836. Rather the proclamation issued by Governor John Hindmarsh announced to the colonists the commencement of colonial government (rather than management by officials of the South Australian Co.), and stated the governor’s intent to protect the rights of Aboriginal South Australians. Nevertheless, the reading of the proclamation was a momentous event and provided a great excuse for South Australia’s first official party.

The governor arrives

The first official settlers left London for South Australia in February 1836. In all nine ships, carrying over 500 colonists, had arrived on the shores of Holdfast Bay by December 1836. The last of these ships to arrive was the Buffalo, captained by John Hindmarsh, who was to be the province’s first governor. The Buffalo anchored off Holdfast Bay early in the morning of 28 December. It had been a long voyage (some on board thought unnecessarily long) and relations between members of the official party were less than cordial by the time they arrived. In fact, the governor’s private secretary, George Stevenson, and Resident Commissioner James Hurtle Fisher had formed a private pact to thwart what they saw as Hindmarsh’s deplorable despotic tendencies at every opportunity. However, on their first day in the province just about everyone behaved well.

More than 200 people were already camped near the shore at Glenelg by December, living in tents and hastily erected huts while they waited for Surveyor-General Colonel William Light to determine a suitable location for the main town. Many had settled into a pleasant, if rudimentary, domestic routine, although there was a fair bit of grumbling about delays in the surveying of land. Amongst the group was Robert Gouger, who had been appointed to the post of colonial secretary. He had arrived with his heavily pregnant wife, Harriet, on the Africaine in September. According to his diary he was just ‘going as usual to let out [his] goats’ when he saw the sails of the Buffalo and the Cygnet arriving. There was great excitement as news of the governor’s arrival spread through the settlement.

Reading the proclamation

At last there were official duties to assume. ‘Required’ to attend to Hindmarsh, Gouger joined others on the Buffalo where they quickly agreed on a program for the day. It was decided that the ‘Governor and emigrants’ should land at once so that the necessary swearing-in of office holders could be conducted and a formal ceremony held. They agreed upon the wording of the first proclamation, a document that Stevenson had drafted on the ship. His commitment to a new social order is evident in its phrases.

It was a tumultuous day for Gouger. The swearing-in took place in his tent. As the senior member of the infant Legislative Council present, the young Gouger administered the oaths of office, including that of the governor. As Hindmarsh and the others gathered in one part of Gouger’s tent, Harriet lay in the other in the early stages of labour with their first child. Harriet had suffered ill health throughout the journey to South Australia and, although they may not have understood it then, was seriously ill with consumption (tuberculosis). As Gouger recorded ruefully in his diary for that day: ‘Rapidly as my heart beat on this occasion … I was not suffered long to bestow even one thought upon it’. This was hardly surprising. But, meanwhile, there was a ceremony to organise, luncheon to arrange and a flag to find – all within the space of a few hours! Everyone scurried about to get things ready.

By 3pm everything was set and the settlers gathered together. Mary Thomas recorded that it was ‘requested that we should prepare ourselves to meet the procession, as all who could were expected to attend. We went accordingly, and found assembled the largest company we had yet seen in the colony, probably two hundred persons’.

The day was very hot so they gathered under the shade of a ‘huge gum tree’. The official commissions were read and Stevenson read the proclamation. Marines from the Buffalo then fired a ‘royal salute to the British flag’ followed by a ‘feu-de-joie’, after which the ‘Buffalo saluted the Governor with 15 guns’. We can only guess what any watching Kaurna people made of this cacophony. The official proceedings over, they all gathered for lunch. A ‘fine Hampshire ham was dressed for the occasion’, according to Mary Thomas, and was the centrepiece of a ‘cold collation … in the open air’. Since the temperature was apparently well over 38C we can probably assume that ‘cold’ was a relative term. However, everyone seems to have been satisfied with the proceedings, including the governor who, again according to Thomas, was ‘very affable, shaking hands with the colonists and congratulating them on having such a fine country’. After several toasts and the singing of the National Anthem (in which a few present mistakenly substituted the old King George for King William), Governor Hindmarsh mounted a chair and, in a fine spirit of generosity, exclaimed: ’May the present unanimity continue as long as South Australia exists’. Ironic words as it turned out, but not, perhaps, so evident on that particular day!

Also somewhat ironic was the aftermath. The proclamation tried to set a lofty moral tone for the province and here again Stevenson’s influence is clearly evident. ‘In announcing to the colonists of His Majesty’s Province of South Australia, the establishment of the Government’, he read,

I hereby call upon them to conduct themselves on all occasions with order and quietness, duly to respect the laws, and by a course of industry and sobriety, by the practice of sound morality and a strict observance of the Ordinances of Religion, to prove themselves worthy to be the Founders of a great and free colony.

How well those assembled heard all of this is debateable, in the absence of amplification, but in any case, these fine sentiments were soon disregarded. ‘[A]ll might have gone off very well’, Stevenson observed sourly, ‘had not our Treasurer got brutishly drunk and conducted himself in his usual disgraceful fashion towards every lady and gentleman present’. And he was not the only one who imbibed too much in the hot sun. Young Bingham Hutchinson, lieutenant on the Buffalo, recorded that ‘the sailors then began to get pretty drunk, so that we had great difficulty to get on board, many staying behind’. On shore they continued to party all night with some of the settlers according to Mary Thomas: ‘It seemed as if some of the colonists did not even go to bed for we heard singing and shouting from different parties at intervals till long after daylight’. It was evidently quite a party!

Who was present at the reading of the proclamation?

It is difficult to be certain who was present at the reading of the proclamation, although Thomas’ diary suggests that all of those in the vicinity were encouraged to attend. Those who recorded the event seem to have agreed that about 200 did so. But it is equally interesting to note who was not present. Although he was in the vicinity, William Light did not attend, recording simply in his diary: ‘I heard of the Governor’s arrival, but having much to do, had not time to go to Holdfast Bay and meet him’. Nor is there any indication that any Kaurna people were present, although they too were in the vicinity. Later that night they apparently fired the bush all around the camp site, ‘which burnt grandly’ according to Hutchinson. Later representations of the event ‘improved’ on it somewhat, adding participants. The most famous pictorial representation of the reading of the proclamation was that begun in 1856 by the newly arrived English genre painter Charles Hill. During the 20 years it took him to complete the scene, Hill interviewed and painted from life at least some of those who claimed to have been present. But, for reasons that are unknown, he also included several people who were not there – Light, for example, and a group of Kaurna are shown standing in the distance. Similarly, although several colonists apparently showed him the dresses they had worn that day, the women present are depicted in his painting in the styles in vogue in the 1850s, rather than 1836. Although described as an historical picture because of its subject matter, Hill’s ‘Proclamation of South Australia 1836’ must be interpreted with care. It is essentially a work of imagination, with some attempt at accuracy.

Comments