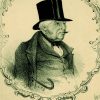

Osmond Gilles, the first Colonial Treasurer in South Australia, is by any description an enigmatic figure, a pastiche of contradictory character traits who lacked internal consistency in his dealings with people and who more than any other person named in Adelaide’s streets could be described as an anti-hero. While Gilles does have some redeeming features, especially his generosity and his economic prowess, he always seems to leave a bad, if bittersweet taste in the mouth.

As the first Treasurer in the colony and therefore one of the foremost colonial appointments, he was, quite rightly, a member of the twelve-man Street Naming Committee which sat on 23 May 1837. However, as one gets to know him it is hard not to think that he was in some way peripheral to the core decision-making processes on that day and not as committed to the agenda being crafted by the younger, more ideologically driven members at the table.

At the point of Adelaide’s settlement Gilles was nearly 50 years old – a generation older than the others present – a spirited individualist, a consummate opportunist and, beyond George Fife Angas, the wealthiest man to emigrate to the new colony.

Gilles was born in Soho, London, on 24 August 1788, the year of the first European settlement in Australia. He was the elder son of Osmond Snr and Hannah Gilles, who lived in Litchfield Street between 1786 and 1799. His brother, Lewis, was nine years younger and there were two sisters, Louisa Ann and Hannah Jnr. The family was Huguenot who, several generations earlier, had come from the coastal township of St Gilles, near Montpellier in the south of France. Their religious inheritance is best described as Protestant Reformist, otherwise known as French Calvinist.

Osmond Gilles was born on the eve of the French Revolution and baptised in St Anne’s on 20 September 1788.

There is a lack of certainty with regard to Gilles’ education, but it is thought he attended the parish school at St Anne’s, transferring later to Mr. Meures’ Academy, the highly regarded school for young gentlemen near Soho Square.

As a young man Gilles was readily accepted into London’s merchant banking class, where he learned to make money and the machinations of capitalism. He travelled to Spain and soon became accomplished at commodity trading, thereafter finding himself in Belgium, where Wellington was preparing to defend the Netherlands.

At about this time he met a young Englishman, Philip Oakden, who was also in Europe on business. Their acquaintance warmed to a friendship and through Oakden Gilles eventually met Miss Oakden, who was to become his wife.

Gilles and Oakden spent sixteen years in partnership, during which Gilles travelled around Europe buying and selling commodities. Some of their business involved sheep breeding and the genetics of high-quality wool production, so they sent Lewis, Osmond’s younger brother, to Van Diemen’s Land as a livestock agent. Opportunities abounded and good money could be made in exporting Saxony stud sheep.

When Osmond’s wife suffered a succession of unfortunate miscarriages and then unexpectedly succumbed to a fatal illness, the partnership was dissolved.

Gilles returned to London where, in a fragile state, he drifted towards the Wakefield theorists who were at the time receiving much publicity, particularly in the radical press.

It was a logical step for Gilles to consider emigrating, and with the excitement building in London between December 1833 and the passage of the South Australia Act in August 1834, he made his intentions known and joined with the other prospective colonists. For many who intended to go it was the practice to linger in and around the offices at the Adelphi in London, in anticipation of an appointment. Gilles was no exception in this regard. Just how early he came to know of the project is not known, but it can be deduced it was sometime in and around 1832 or 1833.

Seeking to endear himself with the proponents of the scheme, Gilles made himself available at all times to the committee of the South Australian Association, formed in December 1833. He was on good terms with Robert Gouger, John Brown and the other young expectant emigrants who committed to the project seeking associated employment.

After the South Australia Act passed through both houses of parliament, and in the euphoria it engendered, those intending to go to South Australia formed themselves into the South Australian Literary and Scientific Association, of which Gilles was an inaugural member in 1834, with a view to learning more about the issues they might face in their new home. The members met weekly to hear lectures and engage in discussion.

These meetings were full of optimism and goodwill. However, in some cases the equanimity was not to last. R. M. Hague reports that by August 1835 Gilles apparently had lost his temper with Robert Gouger, blaspheming as he did and complaining that he had been used by Messrs Gouger and Co. This is most likely a reference to the commercial activities of Gouger’s brother who was in India, where he was a Commission Agent, buying and selling military uniforms and other commodities. Just what the Gouger brothers did to offend Gilles is not known, but given that Gilles also had prior experience in similar enterprises, it is probable that some confidence of a commercial nature had been breached.

The middle of 1835 saw a mad scramble for appointments in the new colony. Gilles and Brown were both intent on the Colonial Treasurer’s position. On 15 May ‘Gilles advised all present at the Literary Association meeting that he WAS going to apply for the treasurer’s job’. Gouger had already received his appointment as Colonial Secretary. While Gilles was fought hard for by Torrens, he ‘was opposed by all who knew him, and Torrens and Hindmarsh were instructed to see him with a view to his retirement’.

Ultimately, however, Torrens as Chairman had his way. Gilles’ extreme wealth rather than his obnoxious personality eventually prevailed, and when he offered to advance the commissioners £1,000 as seed money, pragmatism overtook repugnance and Gilles was appointed Treasurer.

According to Mr Arthur Leake, a wealthy nineteenth-century Tasmanian pastoralist to whom Gilles had exported Saxony stud rams from the royal flocks of Prussia, all South Australians are indebted to Gilles for the outstanding belt of parklands which embrace the city of Adelaide. With a seat at the table during some of the last meetings before departing from Britain, Gilles insisted on reserving park land for the ‘recreation and health of the population’. He had by this time advanced at least £1,000 to the South Australian Colonization commissioners and his threat to withdraw it, should they not support the idea of a park land around the city of Adelaide.

Gilles sailed to Australia on board the HMS Buffalo with Governor Hindmarsh and his entourage. On the Governor’s arrival in the colony on 28 December 1836 there was great rejoicing. Nine ships lay offshore in Gulf St Vincent and in the afternoon more than 200 colonists witnessed the Proclamation of the Province of South Australia. Gilles, however, was unable to control himself and became inebriated. This prompted Governor Hindmarsh’s Secretary George Stevenson to report Gilles to the Colonial Office with his usual acerbity.

The relationship between Gouger the Colonial Secretary and Gilles the Treasurer had cooled to such an extent that they only spoke under sufferance and then only on matters of business. On one occasion, and in the presence of the Governor, Gouger spoke harshly to Gilles and in a manner which implied he was not suitable to be his equal. Gilles was totally affronted by this and demanded an apology in front of the Governor. Gouger expressed his regret to Gilles, acknowledging he had been rather hasty with his words, but unfortunately Gilles could not let the issue go.

Unable to control his anger or his tongue, he went about for months bragging, ‘By God if Bob Gouger [does] not apologize in the presence of the Governor, [I] will blow a hole in his — carcase’. Inevitably Gouger, who was having a hard time of it following the death of his wife and child so soon after arriving in the colony, decided to confront Gilles straight on and resolve the matter once and for all. Seeking the right moment and in the company of Charles Mann as mediator and John Morphett as observer, he surprised Gilles outside a Coltman’s Store and in view of the grog tent. He demanded an apology! Gilles thought it was Gouger who should apologise and replied with a mouthful of expletives. With that, Gouger tweaked Gilles’ nose and as Mann restrained Gilles by the arms, Gouger gave him a beating and a thrashing with a walking stick which Mann had thrown to the ground. It led to Gouger’s unilateral dismissal by Governor Hindmarsh, who was privately thrilled to be given an opportunity to be rid of him by vice-regal prerogative.

Smarting from being summarily dismissed, Gouger sailed back to England to protest his position to the South Australian Colonization commissioners. They responded by repudiating Hindmarsh’s decision and promptly reinstated Gouger. The Governor was immediately recalled on the pretext that he was not behaving in accordance with the underlying principles with which the colony had been established. Governor George Gawler was sent out in his stead and by September 1839 Gilles was also dismissed.

As Colonial Treasurer, there were irregularities in the accounts of the Treasury, which was not surprising, since for much of the time Gilles was operating the public purse with his own money. Some writers claim that he spent at least £10,000 of his own money while holding public office. Douglas Pike maintained that as long as Gilles was prepared to fork out money in the colony nobody was prepared to get rid of him and therefore his incompetence or perhaps lack of due diligence in matters of accounting was easily overlooked. Nevertheless, Gilles’ dismissal under Governor Gawler did appear to be justified and he withdrew to manage his estates.

Despite the antipathy Gilles evoked in some of the colonial officers, in other ways he was a model colonist. He was generous and enterprising in the way in which he settled in the colony. It was reported that his compassion and appreciation of his employees was exemplary.

Gilles’ first recorded act of kindness was to help the Reverend C. B. Howard, the colonial chaplain, erect a temporary structure under which to hold the first Anglican church service in the city of Adelaide. For the first three weeks in the colony, services were held in Gilles’ tent, where they had come ashore at Holdfast Bay, but as the colonists began to gravitate to the temporary settlement where Colonel Light was surveying the city, some other arrangement was necessary.

Gilles and Howard erected a ship’s sail between trees to protect the congregation from the beating sun at a site very close to where Trinity Church now stands, overlooking the Torrens River.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, especially since he was a practising Anglican, Osmond Gilles became a principal trustee of Holy Trinity Church along with Governor Hindmarsh, Fisher and Mann. It should be remembered, however, that in keeping with the principles of religious freedom upon which the colony had been founded, most of the colonial officers contributed in some way to all of the newly formed congregations in Adelaide. In the first two or three years there was free interchange between clergy, regardless of denomination, and they often held services in each other’s churches. Furthermore, the names of Fisher, Morphett, Mann, Brown and Gilles appeared on every church list as contributors, and six different denominational church buildings rose from the ground in the first three or four years.

After Colonel Light and his team had completed the layout of the city of Adelaide towards the end of March, the remaining 591 ‘town lots’ of one acre each were put up for auction. Held over two days on 27 and 28 March 1837 Gilles purchased another 22 lots to add to the first nine he took up in England. The purchase of an acre was always linked to an associated purchase of a country section. In some cases this meant either an 80-acre or 134-acre associated country section, depending on whether one purchased their land in England before they came or at the auction in Adelaide. By this process Gilles had purchased rural land on the Onkaparinga River and at what is today Gilles Plains, Glen Osmond, Oakhampton and Glenelg. He also acquired a number of one-acre blocks in both Port Adelaide and Port Lincoln.

Gilles never failed to give help to the Anglican community in Adelaide. Several of his acres fronted the east parklands down towards Halifax and Gilles streets. He built his first house here, which was one of the early houses completed in the colony, although it burnt down in 1845.

Thereafter, Gilles began a trail of philanthropic undertakings throughout the colony. He began by donating half an acre of the block next door to his house in the east end for the erection of St John’s Anglican Church. The foundation stone was laid by Lieutenant Colonel George Gawler on 19 October 1839. Other donations followed in the embryonic city and included land and material for St Saviour’s at Glen Osmond on section 295 and the church sites for St Paul’s in Port Adelaide, St Luke in Whitmore Square and St Peter’s in Glenelg. Other of his equally munificent donations included land for a public newsroom in Gilles Arcade; land in Hurtle Square for the fledgling Natural History Society; a site for a German hospital in Carrington Street (in 1850); and a site for an Immigration Depot in Port Lincoln.

Gilles built a substantial home known as Woodley on land he successfully tendered for at country section 295 in the eastern foothills, in Glen Osmond. Most of his enterprises were moderately successful in South Australia. He continued his philanthropic work, especially with the thriving German community in Adelaide.

He died on 25 September 1866 at Woodley. Many Anglican churches in Adelaide bear his name on marble tablets. He is memorialised in Gilles Street in the south-east quadrant of the city of Adelaide and is buried in West Terrace Cemetery.

Comments