Colonel William Light is a household name in South Australia. Most would be familiar with his tall and prominent bronze statue, which looks proudly over ‘his city’ from the top of Montefiore Hill.

Three of the six squares on Light’s city plan which lay on the table before the Street Naming Committee on 23 May 1837 were given over to those present. They were Colonel Light, James Hurtle Fisher and Governor Hindmarsh. As might be expected they were the most senior officers and held the highest status in the colony, at least nominally, if not in fact. On this day, the designated architect of the plan which lay before them and the man who decided on the site where they stood was clearly deserving of a memorial. His nomination was surely unanimously accepted.

As Robert Gouger declared: ‘ For the selection of this delightful spot, the plan of the town itself, and the arrangement of the public buildings, the province is deeply indebted to the highly cultivated taste of Colonel Light’. William Julian Light was deservingly memorialised with a square.

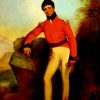

Colonel William Julian Light, his full name rarely noted, was an adventurer and a renaissance man. Described as both a soldier and sailor of fortune, he travelled far and wide in the world. In a relatively short life he set foot in Malaysia, where he was born in 1786; England, where he was raised and educated; India, where his grandfather had been in business; and a raft of other countries including Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, Egypt, Scotland, Ireland, Turkey and Greece, where he served in several military and naval roles.

He was an energetic and versatile young man who turned his hand to many things. He fought bravely under Wellington and was only wounded once in more than forty skirmishes throughout a long and distinguished military career. In the Peninsular War he was attached to the Iron Duke’s headquarters at the battlefront, where his knowledge of mapping and reconnaissance was put to good use. He was also an acclaimed artist, a brilliant topographic draftsman, an able linguist, competent author and a fleeting romantic poet.

Politically he was liberal, which in part explains his friendship with the Napier brothers, particularly Charles Napier who, after refusing the governorship of South Australia, recommended Light for the vice-regal post in the colony.

Colonel Light probably didn’t imagine himself as a governor, but when his friend Hindmarsh was anointed he realised the potential that the new colony might hold for him and his new love, Maria Gandy. He informed Colonel Robert Torrens at the Adelphi that he was prepared to go in a senior post and a recommendation went forward to the Colonial Office that Light be appointed as Colonial Commissioner. This was a brief intended to encompass the roles of both Resident Commissioner and Surveyor General; surely an impossible task even under the best of circumstances. Light was, however, still keen to take up the opportunity. The irony of the situation is inescapable! Light and Hindmarsh were, at this time, the best of friends.

Torrens and the commissioners had hoped the two men would cooperate and together assist the colony to a good start. However, for some unaccountable reason, the commissioners and the Colonial Office abandoned the role of Colonial Commissioner, preferring to split it into two appointments. Light was made Surveyor General and James Hurtle Fisher, Resident Commissioner. The stage was set for the conflict and tension which nearly brought the project down.

Colonel William Light’s accomplishments in Adelaide are well known, especially the brilliant manner in which he designed the city and so carefully laid it upon such eminently suitable topography. Unfortunately, at the time he was labouring over survey pegs during a warm Adelaide autumn he was not to know that he was being subtly and efficiently undermined by his Assistant Surveyor General, George Strickland Kingston.

The commissioners in London had underestimated the extent of the surveying task. Their expectation that a city of 1,000 acre allotments and an equivalent number of eighty-acre country sections could be surveyed while the stakeholders (colonists) sat by in their tents, surrounded by all their worldly possessions, was a faux pasof immense proportions. The colonists had been sent to the Antipodes too close upon the heels of the surveying team. As a result, Kingston was sent back to England on the Rapid, ostensibly to gather more surveying instruments and sundry equipment. When the problem was explained to the commissioners in London, they decided that a much quicker and simpler ‘running survey’ should be conducted. Furthermore, it was decided that if William Light refused to make the change, he was to be relieved of his surveying duties and confined to a coastal survey reconnaissance.

Kingston, a favourite of Rowland Hill and a long-time devotee to the colonising principle, was more closely aligned ideologically to the commissioners than was Light, and he had the confidence, despite his arrogance, of those who mattered at the Adelphi. What Light had not understood or appreciated was just how close he was to Hill (the Secretary) and some of the other radical idealogues on the Commission. On Kingston’s return to Adelaide, Light was so offended by both the tone and content of Hill’s letter that he abruptly refused the Commissioner’s directive. His pride and internal fury at being given an ultimatum to conduct a running survey in the colony, rather than continue with his cadastral/trigonometrical survey, was an insult to his intelligence and he resigned his commission.

The shock of these events weakened his already advanced medical condition and he was finally reduced to a gasping tubercular invalid and a painful death in his small Thebarton cottage.

Colonel William Light died in October 1839. Today he is acclaimed as one of the founding fathers of the city of Adelaide, some say the founding father. Almost everyone in the colony in October 1839 made their way to Light Square to see him interred beneath an obelisk of tribute. Hundreds stood in silence and a number of Indigenous South Australians looked on. Colonel William Light found a unique place in the history of South Australia. Hagiographic he was not. Legendary he is.

Comments