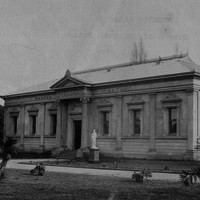

Opening in 1881 in the Adelaide Botanic Garden, the Museum of Economic Botany offers many exhibits outlining the practical and economic use of plant materials. It was the pride of Director Richard Schomburgk, whose international network of like-minded botanists ensured a wealth of content. Though by the early twentieth century the museum was dismissed as quaint and antiquated, and remains today comparatively unknown, its striking Greek revival façade still strikes an imposing figure on the grounds of the Botanic Garden.

What is Economic Botany?

Throughout the nineteenth century, museums devoted to economic botany were commonplace in the English-speaking world. Examples were seen in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, though only the Adelaide building has survived to this day. The reason for the ubiquity of these museums lies in the prominence granted to ‘economic botany’ at this time. As early as the 1930s, though, observers commented on the mysterious and ‘depressing’ name of the building, indicating that the faith in economic botany had dissipated. Modern society has grown even further from the botanical roots of the nineteenth century, with recent decades dominated by plastics derived from petroleum. Thus, economic botany is an alien concept to almost all current visitors to the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

Economic botany, simply put, is the study of plants through the perspective of their practical use for humankind. A potential exhibit could involve a display of a sheaf of wheat alongside various consumer goods and industrial products directly derived from wheat, directly explaining their origins. While economic botany was often disdained by ‘pure’ scientists who critiqued the classification of plant life based on human usage rather than on taxonomic order, it was seen by many as a way to enlighten the public about the linkages between manufactured goods and the environment. As the heyday of economic botany lasted from around the 1850s to 1890s, before the advent of mass-produced petroleum-based products like plastic, these plant-derived goods accounted for almost all consumer products.

The inspiration for all other Museums of Economic Botany was the one at Kew Gardens in London, which opened in 1847. This Museum’s purpose was to ‘make the results of botanical study available to all the world’ by ‘delightfully unveiling quackery’. There was thus a significant element of ‘public good’ to these museums, educating the general public who might otherwise have no formal botanical education. There was also, however, a significant financial element to Museums of Economic Botany, as evidenced from their very name. They were seen as a way to educate the public as to the origins of materials and drugs which enjoyed monopolies due to concealment of their source plants. The idea was that if these monopolies could be challenged by widespread practical knowledge, innovation in manufacturing would surely follow. In this vein, one of the primary arguments that Schomburgk used to convince the colonial government to endorse his plan for a Museum was the potential for economic innovation by farmers who would be inspired to grow new types of plants and start up new manufacturing industries in South Australia.

Development of the Museum

The Museum of Economic Botany in Adelaide has its origins in a previously existing museum in the Botanic Garden. Without a formal name, this building was generally referred to as the ‘rustic temple’ due to its façade being modelled on the Parthenon of Athens, and was built in 1863. It operated as a museum, though it was rather small, and entirely inadequate for the vision for the Botanic Garden held by Director Schomburgk. By 1870, when it had acquired 1500 objects, the building was significantly overcrowded. When it reached 2000 objects by 1876, Schomburgk concluded that the situation was untenable, and a new building was required. In 1877, he petitioned the Government for funding for a new Museum of Economic Botany, to bring Adelaide in line with other Australian colonial capitals which already had their own. His pitch was expressly economic in nature, arguing that the knowledge brought by its construction would encourage diversification in rural South Australian planting patterns, and thus grant a significant boost to the local economy. As this request was made at a time of economic prosperity in South Australia, the Government readily endorsed Schomburgk’s plan. Construction of the building began in 1879 and finished in 1881, and was explicitly based on the example of Kew Gardens. It had sixteen windows of eight feet height, designed to allow in a large amount of sunlight to illuminate the exhibition cabinets. It was built in the Greek revival style, and cost £2900. After the transfer of museum items from the rustic temple, it became officially known as the Wood Museum, hosting a variety of Australian and foreign examples of timber.

Original Exhibits

At its opening, the Museum of Economic Botany had more than 3500 objects to display. The interior design for the exhibition of these objects was directly inspired by the layout at Kew, with cabinets set up for maximum visibility from the large windows. The majority of the items on display were strictly ‘economically botanical’ in nature, designed to showcase the linkages between raw plant materials and the consumer products that they allowed. Yet, it also had a few more unusual collections that were of more specific interest to visitors.

One of the most fascinating displays comprised a set of intricate papier-mâché fungi obtained by Schomburgk from a German source in 1872. These fungi were labelled by colour, depending on whether they were considered edible, harmless, or poisonous. Less colourful were a similar set of papier-mâché fruits, mostly varieties of apples.

Another category of exhibit that enthralled early visitors was a collection of Japanese goods. This collection of food products, commercial goods and artistic creations was first displayed at the Sydney International Exhibition in 1879. At the end of that exhibition, the Commissioner of the Japanese Court for the Sydney Exhibition, Mr Haru-Sakato, sent Schomburgk a collection of the 200 most interesting examples of Japanese products. These included a variety of teas, noodles and fancy paper craft. Newspaper reports on these items repeatedly emphasise the idea that men ‘we call heathens’ were instead wondrous artists and manufacturers, and that after visiting the museum, nobody could ever again look at the Japanese people with disdain, ‘unless they are very ignorant and bigoted’.

One final category of unusual exhibition materials involved a collection of Indigenous Australian cultural objects as well as native foodstuffs. Taking Indigenous knowledge seriously, in a context of teaching non-Indigenous Australians, was highly unusual at the time. These fruits and plants used for medicinal purposes were collected near Darwin by Paul Foesche, the Head of Police in the Northern Territory. While Schomburgk was thrilled that he was able to utilise Indigenous Australian knowledge to improve the South Australian economy, the collection had a dark side. Foesche was renowned for his involvement in massacres of Indigenous Australians, and thus these cultural artefacts were unlikely to have been sourced ethically.

While not directly a part of the Museum of Economic Botany, the building also contained a connected annex for a Herbarium. This room served as a more traditionally ‘scientific’ form of botany, as it comprised a collection of pressed samples of over 18,000 dried plants. This room was designed to appeal to academic students of botany, rather than the general public.

Decline of Importance

Though the Museum opened to great fanfare and initial success, it soon fell into a downward spiral from which it would never truly recover. While Schomburgk remained Director, the Museum prospered. In 1882, twelve busts of prominent scientists were installed, and in 1884 a large ceremony was held to inaugurate the hanging of an official portrait of Schomburgk above the interior entrance to the Museum. His international network of scientific and botanical contacts ensured a constant stream of new material. In 1886, after obtaining almost 2000 specimens left over from the Adelaide Jubilee Exhibition, the Museum harboured over 8000 items. Among the public’s favourites were toxicological specimens like deadly arrow poison of the Macusis of British Guiana, as well as a piece of mummy-cloth from the British Museum. It even contained a piece of wood purportedly from Julius Caesar’s 56BCE bridge across the Rhine. Even as late as 1890, significant new shipments of items would make the newspapers, whose articles praised Schomburgk’s vision, demonstrating the continued public relevance of the Museum. Praise was offered for the fact that Schomburgk’s scientific connections meant that the South Australian Government was never required to pay for items beyond freight charges.

Yet, the death of Schomburgk in 1891 coincided with an economic downturn in South Australia, and the new Director Holtze began a pivot away from scientific learning and more towards public leisure and recreation. The final shipment of new specimens arrived from Kew in 1893, after which almost no new items were received by the Museum. While he did not dismantle the Herbarium officially, Holtze did not share Schomburgk’s enthusiasm for the project, and thus allowed the majority of these original specimens to vanish or be destroyed.

By 1938, after decades of public indifference, a newspaper article was able to describe the Museum of Economic Botany as ‘old and neglected’ with exoticised ‘strange treasures within its walls’, stating that almost nobody who visits the Botanic Garden actually enters the building. It declared that it felt almost ‘sacrilegious’ to intrude upon this quaint old relic of a past generation, unneeded now that the University of Adelaide had established itself as the main source of academic botanical expertise. Without adequate funding, the Museum had languished significantly. In 1933, it had granted its entire collection of books to the Public Library Board (now the State Library of South Australia), and in 1940 granted the entire remaining Herbarium collection to the University of Adelaide.

The Museum of Economic Botany experienced something of a resurgence under the Directorship of Noel Lothian. In 1955, he re-established the Herbarium. By the late 1970s, plans were made to modernise and expand the existing building. While expansion plans fell through, to the pleasure of heritage enthusiasts, a process of decades-overdue modernisation was nevertheless undertaken. In 1978, electric lighting was installed for the first time, allowing significantly increased visibility for the exhibits. This no doubt reduced the sense of the building as fundamentally antiquated in both design and purpose. In 1979, ivy which had covered the façade for decades was removed, and the faded lettering atop the frontage of the building was regilded. Partially as a result of this reinvigoration of the antiquated glory of the structure, the Museum was inscribed on the State Heritage Register in 1982.

In 1983, a series of cases of vandalism, including throwing stones, smoking and unauthorised use of fire extinguishers led to a temporary closure, and the subsequent employment of a part-time attendant. While the Museum had not come close to reaching the heights of public enthusiasm seen in the 1880s, the renovation allowed for something of a return towards contemporary relevance.

Recent History of the Museum

In 2007, the Botanic Garden secured a Federal Government grant of $1.125 million to completely refurbish the Museum of Economic Botany for the first time in decades. As such, it was closed to the public for a significant period across 2007-2008. It reopened in 2009 as the SANTOS Museum of Economic Botany. As a result of this sponsorship, the Museum has incorporated a series of exhibits of local contemporary artwork, as well as maintaining its display of economic botanical objects. The current display numbers over 3000 items, more than 99% of the extant collection, of which around two thirds are originals from the Schomburgk era. In 2014-2015, 60,000 visitors enjoyed the Museum of Economic Botany, a dramatic increase from the middle decades of the twentieth century when almost nobody dared enter the dark, uninviting antiquated edifice.

Adelaide Observer. Museum of Economic Botany. 16 April 1881, p42.

Adelaide Observer. Museum of Economic Botany. 4 February 1882, p29.

Adelaide Observer. Additions to the Museum of Economic Botany. 15 March 1890, p33.

Aitken, Richard, Seeds of Change: An Illustrated History of Adelaide Botanic Garden (Adelaide: Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, 2006).

Aitken, Richard, David Jones and Colleen Morris, Adelaide Botanic Garden Conservation Study (Adelaide: Board of the Botanic Gardens of Adelaide, 2006).

Emmett, Peter and Tony Kanellos, Santos MEB: Museum of Economic Botany (Adelaide: Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, 2010).

News. Strange Relics in Garden Museum. 11 July 1938, p3.

Payne, Pauline, ‘Picturesque Scientific Gardening’: developing Adelaide Botanic Garden 1865-1891’ in William Shakespeare’s Adelaide 1860-1930, ed. Brian Dickey. (Adelaide: Association of Professional Historians, 1992).

Payne, Pauline, The Diplomatic Gardener (Adelaide: Jeffcott Press, 2007).

The South Australian Advertiser. Museum of Economic Botany. 18 May 1881, p7.

South Australian Register. Economic Botany. 27 January 1857, p3.

South Australian Register. The Museum of Economic Botany. 19 May 1881, p6.

South Australian Register. Presentation to Dr. Schomburgk. 31 January 1884, p7.

Wickens, GE, ‘What is Economic Botany?’, Economic Botany 44:1 1990, pp12-28.

Add your comment