The lighthouse that stands near the end of Commercial Road has a history to match its status as an iconic landmark of Port Adelaide’s waterfront. First lit in 1869 near the mouth of the Port River, it replaced a succession of lightships that had operated from the same location since 1840. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Port Adelaide lighthouse was dismantled, and its components separated and used as part of two other beacons. The lantern, which was erected on a screw pile light at Wonga Shoal, was later lost in an accident. By contrast, the steel tower assembled at South Neptune Island remained in use until 1985, when it was deactivated, disassembled, and moved back to the Port. Following a period of restoration, the lighthouse was erected on its current site in 1986 and is currently managed by the South Australian Maritime Museum.

Origins

Efforts to establish aids to navigation in South Australia occurred as early as 1838, when several buoys were deployed to mark approaches to the Port River and define the navigable channel at its entrance. Despite the obvious need for night-time navigational aids at the Port River mouth and elsewhere in South Australian waters, it was not until 1840—following the wreck of the brig Dart and barque Parsee at Troubridge Shoals—that government officials moved to establish a lightship as the colony’s first illuminated beacon. Lightships were vessels with a single, centrally-mounted mast that displayed one or more lights at the masthead at night, and deployed an array of signal flags, markers or other beacons during the day. They were placed on a stationary mooring either above, or in close proximity to, the hazard or navigable area they were meant to mark.

Most lightships were purpose-built, but the earliest examples used in South Australia were converted merchant vessels. The brig Lady Wellington was the colony’s first illuminated beacon and was moored near Light’s Passage in July 1840 to mark the entrance to the Port River. A crew of five pilots resided aboard the vessel and were responsible for guiding other ships entering and exiting the river mouth. They also regularly maintained navigational buoys and beacons, and acted as de facto customs officers. Lady Wellington’s condition rapidly deteriorated and it was soon replaced by the former paddle-steamer Courier (in 1844) and confiscated French merchant ship Ville de Bordeaux (in 1848). Because lightships remained in a stationary position for protracted periods, their hulls tended to suffer the corrosive effects of saltwater and sea air. This, combined with large accumulations of marine growth, rendered them unseaworthy in a relatively short span of time. By 1851, Ville de Bordeaux was starting to show signs of decay, and was replaced by a purpose-built lightship constructed in Port Adelaide. The pilots were relocated to Semaphore Signal Station, where they were able to launch and recover oar-driven pilot-boats and mail-boats from Semaphore Beach.

Port Adelaide Lighthouse

The presence of a beacon at the entrance to Light’s Passage was certainly an improvement from the Port’s earliest days (when no light was present at all), but lightships harboured a number of inconvenient and unreliable attributes that could only be rectified through the establishment of a solid, fixed structure. In 1862, South Australia’s colonial government received a lighthouse lantern originally intended for Port Marsden on Kangaroo Island. With the cessation of mail ship services at Kangaroo Island, the pre-fabricated lighthouse tower (which was ordered and received, but never assembled and erected) was sold to another colony for £500. The associated lantern mechanism did not accompany the tower, but was instead ‘donated’ to South Australian authorities, who stored it in the government yard at Port Adelaide. It was around this time that the government began reviewing options for replacement of the Port Adelaide lightship with a proper lighthouse.

In 1866, the Marine Board decided to use the Point Marsden lantern at the Port River entrance, and erected it on a temporary tower at Point Malcolm (Semaphore South) to test how far its light projected out to sea. The trials proved satisfactory, and the government contracted Alexander Gordon to design the lighthouse tower. Gordon specified that the tower’s central support comprise a nine-foot (2.7-metre) diameter tube of wrought iron sunk through the seabed to limestone substrate approximately 28 feet (8.5 metres) below the low water mark. The tube was manufactured from wrought iron plates with turned edges that slightly overlapped and were bolted together. A thin layer of India rubber was applied at each plate joint to ensure it was watertight. Although the support weighed approximately 40 tons (40 000 kilograms) on its own, concrete was used to partially fill the interior of the tube once it was inserted into the seabed, thereby improving the structure’s overall stability.

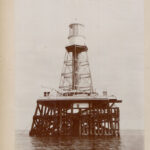

Placement of the support within the seabed proved extremely problematic, and led to lengthy delays in completion of the lighthouse. Adverse weather was a frequent problem, as was the ‘lop’ created by onshore seas encountering strong tidal flow ebbing from the Port River. Efforts to drive the initial support section into the sandbar were inhibited by layers of ‘bungum’ (compacted seaweed, shell and dead marine fauna) that limited the tube’s progress to a couple of centimetres in a single day. Ultimately, a ‘miser’ (a type of large, hand-operated auger) was employed in conjunction with a pair of hard-hat divers ‘of excellent nerve’ who worked alternating shifts within the tube to complete the task. While underwater work proceeded, a crew of approximately 20 builders erected a platform to surround the central support. It measured 50 feet (15 metres) square, was constructed on wooden piles that raised it 20 feet (6 metres) above high water, and formed the ‘foundation’ upon which the lighthouse keepers’ quarters, a storehouse, and boat stowage were built. Delays in construction necessitated that the work crew live aboard the 29-ton schooner Éclair, which was moored nearby.

Initially, the lighthouse keepers’ accommodation comprised a pre-fabricated iron hut that encircled the central support. It proved unbearably hot during the summer months, and was later replaced by a more suitable structure, but was retained and relegated to other purposes. The lantern was originally fuelled by volatile oil extracted from the flowers of the linden tree (Tilia sp.), and entered service on 1 January 1869. The signal it produced was visible—in clear weather—from a distance of fourteen miles (22.5 kilometres). For the most part, the lighthouse was well regarded, although at least one newspaper (Adelaide’s Register) criticised its ‘unsightly’ appearance, excessive cost, and the ‘insufficient’ range of its signal.

Expansion and Renovation

Some of these critiques appear to have been justified, because efforts were undertaken in 1874 to expand and renovate the existing lighthouse structure. A new lantern was ordered from English manufacturer Messrs. Chance & Co., and the lighting apparatus converted to run on mineral oil. The updated system comprised a fixed cylindrical receptacle containing four wicks of various sizes that encircled one another. A Fresnel lens powered by a clockwork mechanism continually revolved around the lantern, and produced flashes at half-minute intervals. An additional 40 feet (12 metres) was added to the height of the existing tower, including accommodation for the new lantern (lantern room) and a ‘light room’ (service room) that contained the clockwork mechanism, fuel for the lantern, and other supplies. Together, these rooms formed a cylindrical space measuring 10 feet (3 metres) high and 13 feet, 6 inches (4.2 metres) in diameter.

The lantern and service rooms were accessed via an internal spiral staircase. Sally-ports in each room allowed the lighthouse keepers access to circumferential external balconies. The first balcony was located at the top of the tower and offered an excellent vantage point from which to view the lighthouse surrounds, while the second balcony was used as a staging point for cleaning the lantern room windows. These windows completely encircled the lantern room and comprised panes of plate glass set into bell metal astragals.

The addition of the lantern and its associated rooms and apparatus added an extra 60 tons (60 000 kilograms) to the lighthouse structure, which necessitated the installation of a network of iron pillars, diagonal support stays and transverse braces. Additional amenities, including expanded accommodation, were installed ‘between decks’ on a platform constructed beneath the old lighthouse keepers’ quarters. When completed, the new beacon extended 120 feet (37 metres) above the high water mark and cast a light that could (in clear weather) almost be viewed at Troubridge Shoals near the bottom of Gulf St. Vincent. It entered service on 3 February 1875 and replaced the old lantern, which had operated from a nearby temporary platform during the year-long renovation effort. Formerly ranked ‘fifth-class’, Port Adelaide’s refurbished lighthouse was soon hailed by local media for its promotion to ‘first class’ designation. The upgrade was by no means cheap: the South Australian Chronicle and Weekly Mail reported in July 1877 that costs associated with refurbishing the lighthouse totalled £28 724.

Damage and Deterioration

For the next twenty years, the Port Adelaide Lighthouse enjoyed an uneventful existence guiding mariners to the entrance to Light’s Passage and the Port River mouth beyond. The arrival of a severe storm in April 1896 shattered the beacon’s two decades of relative tranquillity, and may have inadvertently determined its future. The gale commenced on the evening of 9 April, and at its height in the early hours of the following morning, the sea swept across the lower platform with devastating effect. An array of items, including spare timber, a 200-gallon (757-litre) tank, a stove, several bags of coal and a wooden crate containing sections of plate glass, were washed overboard. A similar fate would have befallen the keepers’ quarters, had they not been moved back to the upper platform during the previous decade. As it happened, seawater did enter the dwelling, but only caused minor damage because the keepers had the foresight to move their furniture and personal belongings to a more protected part of the lighthouse. Waves shattered a ¼-inch (0.6-centimetre) thick window, and repeated blows against the structure caused ‘everything in the place [to be] violently and repeatedly shaken throughout the day’.

The lighthouse was deemed unstable during a structural inspection three years later, and its instability may very well have been a consequence—at least in part—of the 1896 gale. Supporting architectural elements, such as the wooden piles beneath the platform, were showing clear signs of deterioration. In addition, several piles were progressively exposed as the seabed around them was loosened and removed via tidal, current and wave action. Enlargement and subsequent migration of the adjacent navigation channel in Light’s Passage was one culprit. The channel began to shift southwards (away from the lighthouse) as a direct consequence of efforts to widen and deepen it, which in turn caused sediment around the beacon’s base to slump and erode. By 1899, seabed conditions around the lighthouse had deteriorated to such an extent that the overall structure was reportedly ‘shaky’.

Move to South Neptune Island

South Australia’s Marine Board considered a number of options for the Port Adelaide Lighthouse, including repairing or replacing the entire structure, but ultimately decided to dismantle and redistribute its components to other locales. The lantern was installed on a screw pile tower at Wonga Shoal near Semaphore, and was in operation until 17 November 1912, when the light was struck and destroyed by the three-masted barque Dimsdale. Two lighthouse keepers, Henry Franson and Charles McGowan, were killed in the incident, which occurred in calm, clear conditions and was later blamed on the negligence of Dimsdale’s master.

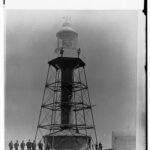

Port Adelaide’s lighthouse tower was dismantled and reassembled on South Neptune Island near the entrance to Spencer Gulf. South Neptune Island was the site of the wreck of the cutter Frances in 1840, and the lack of a beacon in the Neptune Islands archipelago was considered a factor in the subsequent loss of the vessels Emily Smith (1877), Mars (1884) and Loch Sloy (1899) on the western coast of Kangaroo Island. The wreck of Loch Sloy in particular, which resulted in the deaths of 31 of its 34 crew and passengers, was still fresh in the minds of South Australia’s citizenry and government officials, and no doubt had a significant influence on the beacon’s placement.

The site chosen at South Neptune Island was bleak and windswept, and its remote location necessitated that several elements of infrastructure be built before the lighthouse itself was erected. A wooden jetty was constructed first, and situated on the north side of the island in a relatively protected lee shore. It became a valuable lifeline for those responsible for operating the lighthouse, as the island had no natural water source and proved largely inhospitable for plant cultivation and pastoralism. The jetty was followed by a stone storehouse, which was erected immediately adjacent to the shoreward end of the jetty. Three adjoining cottages were built for the lighthouse keepers at the top of the island’s highest point, approximately ¼ mile (0.4 kilometres) from the jetty. The cottages were constructed from stone and each featured five rooms. The lighthouse was erected a short distance from the keepers’ cottages and, due to the island’s granite substrate, took even longer to assemble than it did at the entrance to the Port River.

When completed, the South Neptune Island Lighthouse stood 180 feet (55 metres) above sea level, and featured a second order dioptric light manufactured by Messrs Chance & Co. The light comprised a ‘six-wick Trinity lamp’ that rotated within a pool of mercury—the first time this innovative lantern design was used in Australia. Mercury generated less friction, ensured the regularity of the lamp’s revolving motion, and was an improvement over older ‘roller’ designs then in use. The light was timed to complete a rotation every 50 seconds, and featured its own unique signal comprising ‘a group of three white flashes at intervals of 10 seconds, with an eclipse of 30 seconds’. It entered service on 1 November 1901 and was reportedly visible from the Althorpe Islands (61 kilometres away) in clear weather.

Return to Port Adelaide

After 84 years of service, the lighthouse was decommissioned and replaced. All of its dismantled components were acquired by the South Australian Maritime Museum and moved to a storage depot at Largs Bay in 1985. Over the course of the following year, the lighthouse was restored and ultimately reassembled at its current location on Black Diamond Square at the end of Commercial Road in Port Adelaide. Its opening on 13 March 1986 was timed to coincide with Adelaide’s Jubilee 150 celebrations. Today, the lighthouse is managed by the South Australian Maritime Museum and offers visitors the opportunity to climb to the lantern room and visit the original keepers’ quarters.